This article is also available in Italian / Questo articolo è disponibile anche in italiano

COP29 in Baku opened against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s re-election. While the announcement of the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement casts a heavy shadow over the future of global climate action, China may well emerge as the hero of the moment.

The People’s Republic arrives at the Baku summit boasting a series of significant energy transition milestones: 1,500 GW of installed renewable capacity, accounting for 50% of the nation’s total generation; an unrivalled dominance in global renewable and electrification markets; and, according to IEA forecasts, the strong likelihood of reaching peak emissions as early as 2025 and being the only country to triple its renewable capacity by 2030.

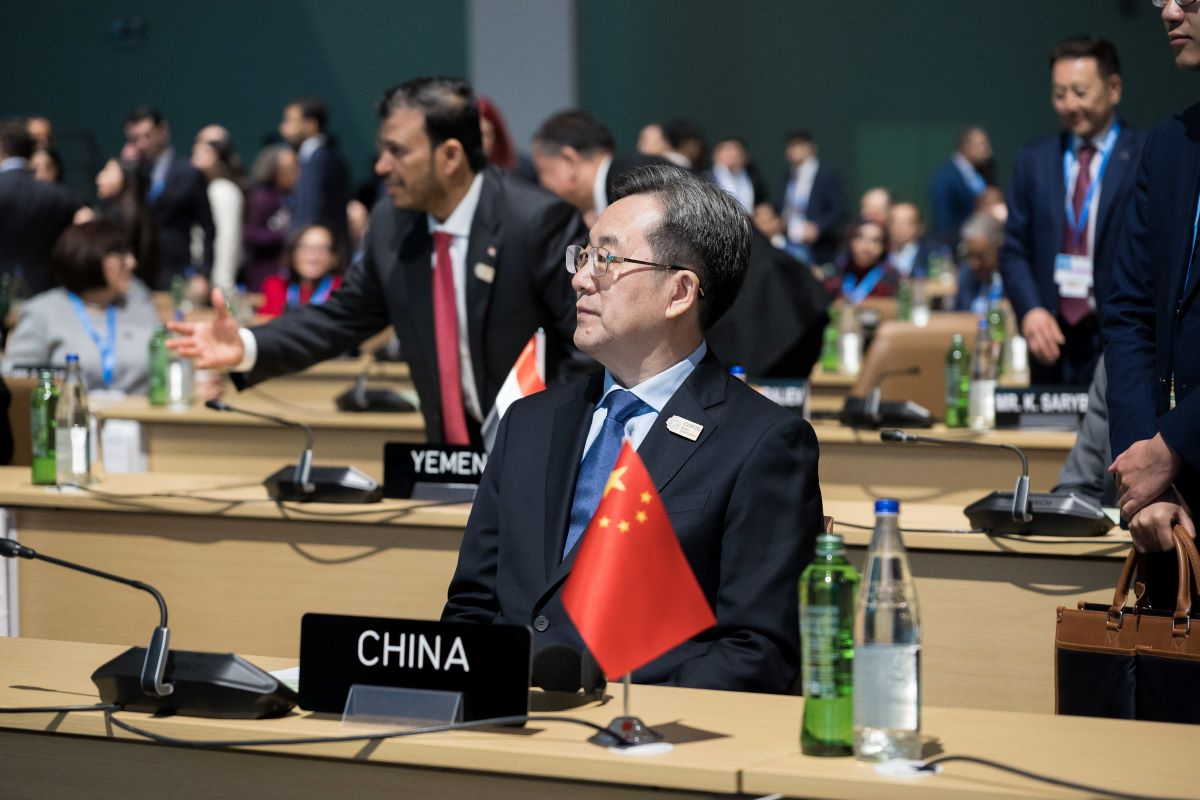

China’s customary reluctance to make extensive commitments to international agreements persists, particularly regarding climate finance, which necessitates transparency in investment accounting. However, the opening days of COP29 have already brought unexpected developments: on Wednesday, 13 November, Chinese Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang announced, for the first time, a quantitative assessment of China’s financial contributions for climate.

We discussed the role, goals, and expectations of Xi Jinping’s China at the Baku Climate Conference with Belinda Schäpe, Chinese climate policy expert and analyst with the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) in London.

A year ago, on the eve of COP28, China and the United States signed the Sunnylands Statement, formally expressing, for the first time, their willingness to cooperate on climate action. But now, the landscape has shifted entirely. What will a new Trump presidency mean for climate cooperation between the world’s two largest emitters?

Trump has announced multiple times that he wants to pull out of the Paris Agreement and the UNFCCC more broadly, and it is very likely to happen. It is also very likely that US-China national bilateral climate cooperation will cease. This is very unfortunate because in the past it has very much contributed to laying the ground base of negotiations on the multilateral level – the Paris Agreement being the key example of that, but also others along the way. This is quite unfortunate, but I think that in terms of subnational and cordial cooperation, it is probably likely going to continue. For example, California has a special cooperation with Chinese counterparts, and I think a lot of people on both sides have been preparing for this scenario and for potential collaboration to continue. Yet the Trump administration will certainly make it a lot harder for bilateral cooperation on climate, but also for the broader relationship, if you consider that climate action was one of the cornerstones still holding up against the rest of the very tense geopolitical relations between both sides.

Do you think this new position of the US will somehow allow China to present itself as the “new hero” of climate?

Yes, I think it will make it much easier for China to kind of portray itself as the more responsible global power, as they like to say, and the new climate leader in the field. They don't have to do much more than just stay committed to the Paris Agreement. On the other hand, this will not make the climate change problem go away for China, which faces significant impacts. If the US was really going to withdraw and if global emissions were going to increase more under the Trump administration than they would have under a Democratic administration, that also has significant impacts in terms of China's own climate risks. Xi Jinping as well as other senior Chinese officials have made it clear several times, also ahead of this COP, that China is involved in climate action for itself and not for any other country. It seems likely that China’s commitment will continue, yet they are undoubtedly well-placed to strategically exploit the US withdrawal.

On 6 November, the day after the US elections, China published its Annual Report on Policies and Actions on Climate Change 2024. The report reiterates that China will strive to peak emissions in 2030. But last year, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicted that the country would likely peak in 2025. Who should we believe?

There are two different dynamics here. One is that there is a lot of hesitation from policymakers in Beijing to commit to an earlier peak. Thus, lots of recent high-level policies still anticipate a late peak just before 2030, and that remains the top line. I think that is quite worrying because the real economic trends are different. At CREA, we are tracking China's emissions quarterly, and what we are seeing is that if emissions went down in the second quarter of this year for the first time since the Covid 19 restrictions lifted, additional emissions stay stable in the third quarter of this year. So, it kind of depends on what the fourth quarter will bring, but there is a potential for this year's Chinese emissions to be lower than the ones of last year. What is driving this trend is the buildout of renewables, especially in the power sector, which is pushing coal into decline and leading to stabilising or decreasing emissions. We are also seeing emissions fall in other industrial sectors, including steel and cement.

This is therefore a positive trend in terms of China potentially reaching an earlier peak. However, the hesitation of policymakers is worrying because they seem to be using the fact that China has not yet peaked as an excuse not to commit to more ambitious targets.

Speaking about commitment, the report is very clear on another important point: China’s unwillingness to open the discussion about its “developing country” status. How long they could maintain this position?

It is a big question. I think there is increasing international pressure, especially from European countries, but also other small island states, for China to make a bigger contribution to climate finance, a central topic of COP29. However, China maintains its stance on "developing country" status also because any change would impact not only its position within the UNFCCC but across numerous other multilateral frameworks. This shift would carry significant implications for China's status in the WTO and the World Bank. It would also send a domestic signal to Chinese citizens who perhaps may not have yet benefited much from the country's development — a development which may slow in the future. I do think there is a way forward in terms of China's contribution to global climate finance, and I hope this will emerge from COP29. China is already a big contributor to global climate finance. Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang announced for the first time a quantitative assessment of China’s climate finance contribution in his address to the leaders’ summit at COP29. He said that, since 2016, China provided and mobilised 177 billion RMB (24.5 billion dollars) to support developing countries in addressing climate change. China’s willingness to quantify its contribution to global climate finance is a huge step and will lay the groundwork for finding a compromise on the New Collective Quantified Goal at COP29. It may also put more pressure on other developed country donors to significantly step up their game. This announcement means that China contributed an average of 3.1 billion dollars per year, which would put it in 6th place among the largest climate finance donors behind Japan, Germany, France, the US, and the UK, according to analysis by the World Resources Institute. Of course, at the moment, it is unclear whether these numbers are comparable in terms of the definition of climate finance and through what channels they have been provided. Now it is about trying to find a way to make these contributions count within the multilateral framework. To do that, China will have to share more details on the quality and channels of the finance provided so far and clarify its future contribution. That would make it easier for us as an international community to assess what China’s climate finance contributions are, now and in the future. I think, to be honest, it is actually a positive story for China to tell, and they are just not telling it at the moment. They are keeping their data, well, not very transparent.

The document is also very direct about the topic of protectionist measures. It states: “some countries have formed ‘small circles’ and implemented unilateral protectionist measures”, especially for low-carbon technologies. What about the so-called BASIC group (Brazil, South Africa, India, China) initiative to start “a fight over trade measures”? Could they achieve any success on this point?

They were really keen to get this point on the COP29 agenda, but in the end, they ceased. They tried it already last year at COP28. Obviously, it is somewhat of a background noise. China has raised this point since the EU announced the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and the BRICS countries have raised their criticism. However, I think in terms of CBAM itself, China's actually beyond the political narrative and quite accepting of it. There is a lot of preparation for companies to comply with the EU CBAM that is well underway. There has been a lot of diplomatic engagement on the higher level, and on the technical level, to make it work. Obviously, most recently the EU tariffs on EVs added another layer to that, and that is what I think this paragraph hints at. It is not only about CBAM, it is now also about tariffs and the Chinese challenge towards the EU, and, of course, the US, Canada, and others: “What are you trying to do by undermining our clean tech exports to the rest of the world?” I think this is a discussion that will continue.

One last question: I would like to know your opinion on the new Chinese special envoy for Climate, Liu Zhenmin. This is his first COP after the veteran Xie Zhenhua’s retirement...

I think it is a bit early to assess his role. Xie Zhenhua is still somewhat in the background: he is not at this COP, but he was part of the European delegation with Liu Zhenmin going to Paris and other European governments. Liu has very big shoes to fill, but on the other hand, he has more of a foreign policy background, which is increasingly relevant in the discussions. On a more personal level, Xie Zhenhua and John Kerry had this very special friendship, and I think it facilitated a lot of US-China engagement, even at times when it was really difficult. We will have to see how the relationship between Liu Zhenmin and John Podesta develops — and to what extent it could serve as a similar cornerstone.

Despite the Trump administration?

Yes. I think the new Trump administration opens a window for more EU-China collaboration. I believe the Chinese side is very keen to deepen relations or engagement with Europe on climate topics. And now, with Trump being elected, there is an opening for both sides to reconsider how they want to frame these bilateral relations. I think Liu Zhenmin could play an interesting role in that.

Cover: Liu Zhenmin, country's special envoy for climate change, at COP29 © COP29