Forced to watch it from balconies and windows, a city, to those who have experienced urban lockdown, appeared as an unknown and largely misunderstood object. In the frenzy of production, a kaleidoscope of opportunities, events, the hustle and bustle of human activity and the din of machines, the desire of endless growth, 21st-century cities have suddenly appeared to us as a foreign object, alien to our wellbeing, disconnected from the harmony of nature and human spirit.

Very few events such as the Covid-19 crisis have led to a rethinking of large urban structures, to doubt the quality of life of large cities, to understanding connections amongst health, resilience, sustainability and prosperity. We’re back to studying and re-planning such overcrowded spaces derived from an increasingly numerous social animal who is less and less inclined to live in liminal areas, to choose marginal and peripheral areas, mountain and hill villages. We have understood that there must be a before and an after in city life.

Architects will take exception and say that to them cities have always been subject to investigation and analysis. But considering how urban areas are currently created, how space in large cities is planned – its endless sprawl – you would think that only very few avant-garde people truly did their homework appropriately, perhaps too much enthralled with flashy facades, archistar masterplans and ideas where form overpowers function. It is high time neoliberalism abandoned urban spaces in favour of a circular philosophy.

Urban metabolism

First things first: structure. How can we reach a good city form, as the late geographer and urban planner Kevin Kynch would put it? Cities are more and more regarded as an organism, made of countless ganglia, networks (flows), spaces, players interacting with each other. Just as a healthy individual has a perfectly functioning metabolism, a healthy city must have an efficient urban metabolism. It takes the bear minimum of matter, water, energy, it knows incoming flows of goods and people, it optimises every element entering its metabolism (energy, materials, but also intellectual resources and finance), it grows without producing harmful waste (particulate matter, greenhouse gases but also social disparity, unemployment, poverty). At the same time, it enjoys mental as well as emotional wellbeing. There’s nothing like happiness and optimism to cure any ailment.

Furthermore, if it’s true that cities can be compared with biological ecosystems, then as any other living organism, they can find survival and adaptation strategies also and especially in moments of deep crisis such as those we are experiencing.

City resilience

This is where we need to develop resilience. The latter is a system’s ability – a human organism, a city, a community, a company, an ecological or socio-economic system – to adapt, restoring its functionality and innovate after enduring external impact, a shock or a natural or human-induced stress.

To create elements of resilience and circularity one can start from functions. Reflecting on how walking and cycling can work alongside local collective public transport as a mobility choice, on the ways to make green areas and public spaces truly available to children and the elderly, reducing the only anti-economic investment in history, cars, lying around unused 93% of its life span.

In general, we must ponder on what shape our future living will take. If it is true that we will be looking for larger properties, with a garden in quiet areas outside the hustle and bustle of city life, it is also true that cities will not die out, but they will necessarily have to reinvent themselves. So, why not do it in a resilient, circular, inclusive and fair way? Could this be the New European Bauhaus?

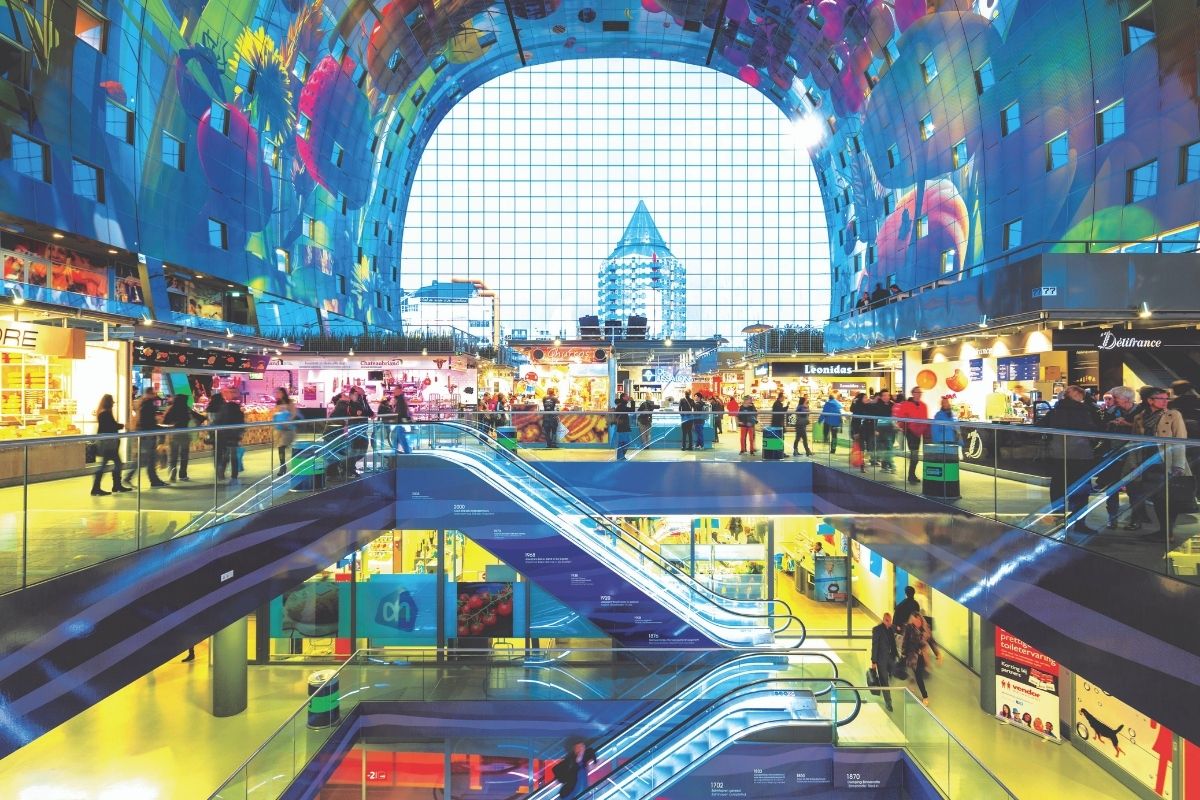

There are many local governments committed to fighting climate as well as pandemic change with tangible projects and choices including the ambitious ForestaMI plan, three million trees planted in Milan and the 133 metropolitan municipalities by 2030; the new timetable plan, open squares and roads in the city of Milan; the Urban Jungle experiment in Prato, highlighting the importance of green areas and wellbeing. Or London, with the super urban cycle highway, Rotterdam’s Sponge Garden, the inclusive green-roof programme in Buenos Aires, New York’s Pop-up car park, inspired by the visionary Oceanix City project, developed by Bjarke Ingels Group.

The pandemic highlighted the characteristics that can make communities resilient to emergencies and people are more aware of “individual as well as collective fragilities.” Therefore, it has emerged how only collective reactions can heal the wounds of a hurt community. Along with such responsibility, an equally strong awareness of the importance and the presence of the government has emerged. So, it is all the more clear that in order to have healthy cities, it is necessary to work on resilience and circularity in public structures. Because of its transversality, resilience works as an enabler within local authorities. For total city rethinking of its functions, multidisciplinary teams or co-ordinating figures are needed in order to achieve transversality in practice. To do so, mediation and diplomacy must be promoted at public level. These are fundamental to act within local authorities characterised by a strongly hierarchical structure.

Circular cities, a trip around the world

To restore health to our cities and make them resilient will not be easy. This issue of Renewable Matter is a slimming programme, a fitness plan for our cities, starting from the transition from linear, oil-capitalist cities to circular ones. An around the world journey to discover different types of knowledge, from the Netherlands to Colombia, to the USA and Italy to understand how we are starting to apply this transition. Paola Pluchino will acquaint us with urban metabolism models and digital twins. Antonella Totaro will illustrate the Dutch model of circular cities, but above all she will introduce the topic of circular living, exquisitely examined in the interview with Carol Lemmens in Arup, which will be further investigated in Renewable Matter n.38, wholly devoted to circular construction. Urban planner Cassim Shepard will talk about the involvement of city dwellers as a way of rethinking public space and making the relation with non- urban areas sustainable. Bogotá will teach us a lesson on how the circular city model varies from region to region and how newly industrialized countries can accelerate and overtake even the Old Continent. Many case studies, starting from Enel which has turned the topic of circular cities into its banner. Last but not least, Nextchem with its circular districts for energy and materials; Gruppo CAP illustrates, through Rudi Bressa’s pen, the topic of water in circular cities. This issue does not certainly claim to solve the problem, but it intends to provide some food for thought in a debate which promises to be ever more interesting. For the time being, enjoy reading our pages!

Download and read the Renewable Matter issue #36 about Circular Cities.