Upcycling upon upcycling. This is how we could define the new upcycling experience carried out by Favini based on the use of wine pomace after the distillation process for the production of paper: the new Crush Uva.

But this is a story, like all those about the circular economy that must be told properly, starting in the Veneto vineyards, known for their “historic” wines such as Pinot and Merlot, near Bassano del Grappa. Because it is here that our bunch of grapes, whether it is white or red, starts its journey: from vineyard rows to paper. Jumping from one sector to the next and producing “cascade value” every step of the way as Gunter Pauli, The Blue Economy’s father would say. The first step is grape harvest, followed by pressing to obtain must which will turn into wine. This wine is already part of a local identity. Its residue, the wine marc, in a mix between tradition and innovation, offers a different product, grappa, whose by-products – we had better call them like this – have had a life of their own for years. “The pomace we use to distil our products (grappas, liqueurs, digestifs and aperitifs, editor’s note), after being processed has had a life of its own for years” as Andrea Mazzoli says – director of Nardini, the historical distillery, founded in 1779, 50 employees, 3,800 hectolitres produced every year and about 10 million turnover yearly. “Since the 70s, for us, grape pomace with its components, skins and grape seeds is no longer waste”. The former is used as animal feed and the latter is sent to oil mills, where grapeseed oil is manufactured in the food and cosmetics sectors.”

|

|

Andrea Manzoli

|

To give you an idea of what Nardini does in quantitative terms we need to consider that the incoming raw material is represented by 10 million kilos of grape pomace with a yield of distillate between 3.2 and 3.8% in continuous plants and 4% in discontinuous ones, which we could regard as historical factories. The yield of secondary raw materials, i.e. by products,is 20%.

Once the distillation is over, a dealcoholized grape pomace is obtained which is then sent to a drying kiln: here warm air is blown until it is dried with a humidity lower than 10%, after this skins (which are ground) are separated from seeds and the secondary raw materials are sent to a new life. The process is renewable. Because 20% of secondary raw material is used to generate the necessary heat for the drying and once this is finished it will heat up the offices.

“A few years back, for energy production we used the woody part of seeds from the oils mills after extracting oil” adds Manzoli. “Since to extract oil a solvent is necessary, to generate heat we preferred to use part of the skins and seeds before oil separation.” This decision is significant, though, because in the rising industrial production chains of the circular economy every piece of the puzzle must fall into a specific place. In order to do so, a systemic view is necessary, able to assess the value chain, with its environmental implications, along all the new production chains.

Contrary to what one may think, this process has some economic value. The 2 million kilos of secondary raw materials produced every year are worth €15 to 17 per 100 kilos – totalling between €300,000 and 340,000 – which is constantly rising due to the possibility of its energy use as well.

But let’s go back to our journey: skins and seeds are at a crossroads. Cosmetics and animal farming against paper and perhaps energy. But actually there is no real competition.

From Grapes to Paper

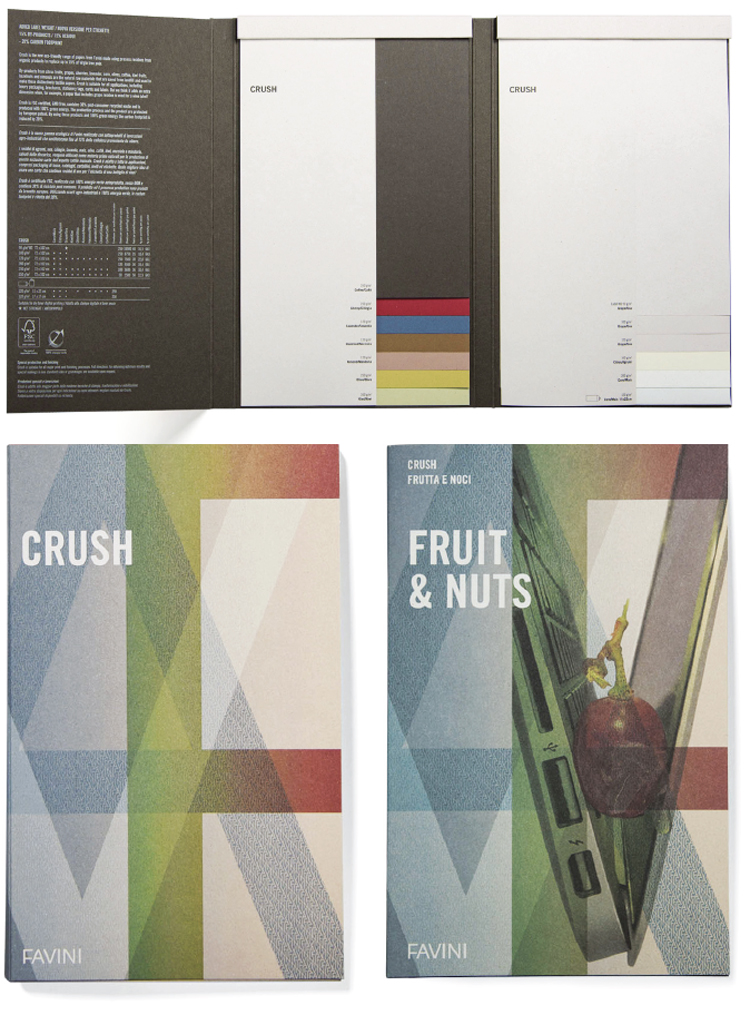

Crush Uva falls within the wider picture of Crush papers produced by Favini with waste and by-products from agro industrial processing. Such secondary raw materials replace up to 15% of cellulose from plants. Up until now, residues from citrus, cherries, lavender, maize, olives, coffee, kiwi, hazelnuts, almonds and grapes are used and rescued from landfills. Crush paper is FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certified and is almost entirely produced with renewable energy. It is OGM-fee and contains 30% of post-consumer recycled material. In this way it has a 20%-reduced carbon footprint compared to ordinary papers.

“The process used by Nardini is not so widespread as one may think” claims Achille Monegato, Favini’s director of the research department. “Others, most distillers, do not dry pomace, at best they us it to produce biogas or as soil improver, or they sell it wet, after dealcoholizing it, a state that makes it unusable for the production of paper. Nardini understood that by drying grape pomace, it would give it a second life and it would become, as it happened, a new source of income.” Singing from the same song sheet in a panorama of small players, such as distilleries, can be a problem, not least because few are large enough to buy a drying kiln. “We would like to cooperate with Nardini which is a top distillery and a very strong brand,” adds Monegato. “With this experience we could create another market, through the use in the paper factory of dealcoholized and dried grape pomace, increasing the price since demand is growing. In this way a new production chain could be created, because at that point distillers would have to equip themselves with drying kilns.”

So, supply chains are intersecting each other, but carefully and gently, because many factors come into play when it comes to industrial systems. Favini’s rationale, where Crush Uva is just one of the kinds of paper used as secondary raw materials, is clear. It is imperative that we should use raw materials, even second raw materials, leaving the food sector unaffected. In other words, no material directly intended as food must be employed to produce paper. “If everything, process and material, moves in the direction of the circular economy, it is then clear that our journey does not make much sense – continues Monegato – but if only one fraction of the existing quantity of some material – such as grape pomace – is reused, then our intervention makes sense. And a market is also created.”

The amount of pomace-derived matter present in the new Favini’s paper is 15%, which improves the product’s LCA, because in this way high-quality matter is replaced with a by-product from another production chain through an upcycling process.

The great challenge for these kinds of paper, which pose no problems for their technical management as they can be treated as the normal ones for the printing and paper processing phases, is to be “grasped” from a “cultural” viewpoint. The most appreciated novelty is the tactile and visual aspects. Indeed, Crush Uva is light grey with little dots on the background, a peculiarity of the by-products used. “Since the very beginning, we decided not to purify it of whiten it with additional chemical processes, leaving it as it is with its “imperfections” which are sending a message.” So, the challenge is to offer a material that would allow the wine sector to step up the marketing and image front, by resorting to the circular economy. That is packing a product with paper embodying material deriving from its own very sector.

Grape pomace and Sundries

With reference to this new industrial production chain the type of secondary raw material necessary to distilleries should also be taken into account: grape marc. Red grape pomace has a higher yield, both in terms of skins and seeds that are more abundant. The colour only concerns paper factories and not oil or feed mills. Pomace must arrive at the distillery within 24 hours from pressing, for if not its distinctive characteristics will be lost and the onset of mould growth occurs. For this reason, the supply chain must be short. Nardini gets its supplies between the Brenta and Piave, and the process must work around the grape harvest season, first the white vine variety such as Pinot and then the reds such as Cabernet and Merlot. Once the grape pomace reaches the distillery, between August and the end of October, it is put into silos, pressed to take air away and fermentation begins in an anaerobic environment where a mushroom, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, turns sugar into alcohol. Then distillation occurs according to pomace type. This is the reason why if a paper mill like Favini needed white skins it would have to collect them between October and November, when Pinot is distilled. Intersecting agricultural and industrial supply chains with their differing deadlines and methods is quite something.

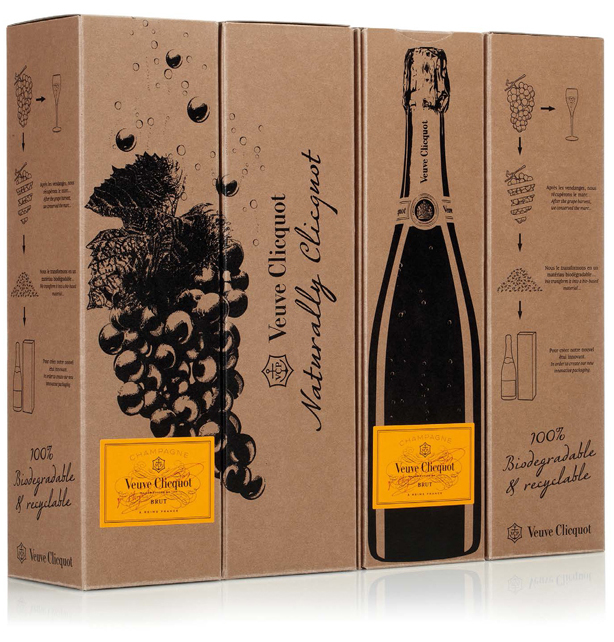

It is a challenge that has been accepted by none other than Champagne. As it happens, Crush Uva has been selected for the packaging of “Naturally Clicquot 3” new champagne line by the French maison Veuve Clicquot. “Wine has a great appeal and to be able to associate our paper to wines, even high-quality ones, represent a very good opportunity where the concepts of creative reuse of materials find an ideal combination” Favini’s CEO Eugenio Eger claims. In the work done with Veuve Clicquot, the objective was to create a kind of packaging for a new product that had to be in line with the high-profile and distinguished image of the French company which has some specific features even within the champagne producing sector. “Veuve Clicquot’s aim is not the distinguished glittery and metallic image of most champagne producers, but it boasts its unique characteristics that sets it apart from all others” adds Eger. “It would have been impossible to carry out this kind of operation only five years ago. I was utterly impressed when I met with Veuve Clicquot’s marketing department. They were very daring, they made a very brave leap in changing drastically the glossy set up of their image.” The impression that one gets by looking at “Naturally Clicquot’s” packaging is that they wanted to embark on a unifying journey between a more polished image and the natural character of the new product”, adds Eger. “It is obvious – he claims – that they perceived that the eco sustainability connotation is a rewarding element even within the luxury products realm and the French company is now the forerunner of a rationale that could spill into other goods’ sectors.” But there is more. One of the four corners of the box is devoted to the brief and effective explanation with info graphics about the process necessary to produce it.

It is a clear choice. To give tangible value to the content of sustainability as a whole, packaging included. Now the big challenge is to spread this logic to the rest of the wine sector, starting from labels and promotional material and by developing a marketing rationale where eco sustainable content becomes a message. Actually, the content itself, thanks to its ecological characteristics becomes part and parcel of the message.

Info