In the evening of Thursday, June 13, the preparatory work of SB60 came to a close and, in the general discontent hovering at the World Convention Center in Bonn immediately following the close of the plenary session, statements from Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the UNFCCC were quick to come. “We took a detour on the road to Baku. Too many issues were left unresolved. Too many items are still on the table. […] But we have left ourselves with a vast amount to do between now and the end of the COP”, he commented.

From June 3-13, some 6,000 people - including delegates from 198 countries, activists, NGOs, and other civil society actors - flooded Bonn, the German town that is home to the UNFCCC Secretariat, to attend the interim climate negotiations involving the so-called Subsidiary Bodies (SBSTA and SBI).

An annual event, the Bonn Climate Talks are preparatory meetings that give governments from around the world the opportunity to take stock of what happened at the previous COP - discussing in particular how to implement the agreements - and dictate the policy direction for the next one, working on preliminary drafts that will serve as formal recommendations to guide negotiations in Baku, Azerbaijan, the host city of the next climate conference, scheduled for November.

Cecilia Consalvo, the Bonn correspondent for Italian Climate Network who followed the first week of negotiations, shared her impressions with us, "Personally, I felt great haste and agitation mixed with a rather low level of ambition, which created slowdowns in the negotiation phase of some texts. The weight of the Developing States and the urgency to act that these countries brought to the negotiating tables was very present at the working tables we covered, from climate finance to energy and agriculture. And yet what we found was an almost total lack of cooperation between North and South, with great divisions on very important issues."

Among the crucial issues that catalysed the attention of delegates and observers during this SB60, climate finance stands out above all, and it’s no coincidence. In fact an agreement on the so-called New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), a new quantitative climate finance target to benefit countries in the Global South, is expected to be reached at COP29. Significant progress was therefore expected at these intermediate negotiations to accelerate the work and the negotiations that will resume in November. In Bonn, however, Article 6 of Paris, which has never been made fully operational after COP21, and transparency mechanisms were also discussed, with important news coming from the Biennial Transparency Reports (BTR).

New Collective Quantified Goal: the road to Baku is uphill

Let's start with climate finance. Throughout the two weeks of negotiations, all eyes in Bonn were on the drafting of the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG), the new climate finance goal that should be formalised at COP29 thus enshrining the overcoming of the notorious $100 billion/ year target by 2020, set at COP15 in Copenhagen back in 2009, but only achieved in 2022.

In the first week of the conference, the path to the identification of the NCQG started uphill, beset by many difficulties and hampered by recurring tensions between Developed and Developing States, which paralyzed the negotiations. On the one hand, countries such as the United States have remained steadfast in their position to keep this new goal separate from the provisions already included in the Framework Convention on Climate Change, reaffirming their willingness to create a new source of funding on a voluntary basis − previously expressed at a meeting of the Ad Hoc Work Program (AHWP) held in Colombia last April − and to broaden the pool of donor countries by involving the emerging economies of China and India.

On the other hand, countries from the Global South, primarily delegations from Pakistan and small island states such as the Marshall Islands, have pointed out that demanding the Developing States' contribution to the NCQG would be a violation of Article 9 of the Paris Agreement. (This, based on the UNFCCC's principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities, enshrines the duty of developed countries to invest in climate finance to further the sustainable development of countries in the Global South.) However, they also reiterated how increasing flows into climate finance represents an existential issue for the poorest states, an essential choice not only to address the climate crisis but more importantly to ensure the survival of their communities.

Not even during the first half of the second week did any shared solutions emerge regarding the timing and amounts to be allocated and in the text of the second draft there is no agreement on the so-called quantum, i.e. the amount of the new annual target. This is in spite of proposals put forward by the G77 group, led by the Alliance of African countries and by China, which put on the table a target of $1.1 trillion a year to be financed by taxes on strategic sectors such as technology, finance, defense and fashion.

On the evening of Thursday 13, following two intense weeks of negotiations that saw the Parties engaged in drafting a preliminary negotiating text to be brought to COP29, the concluding plenary of SB60 decreed its verdict. The endless hours of negotiations did not produce the hoped-for result, and although expectations were high, the preparatory text on the NCQG was not approved. The Co-Chairs therefore called on the Parties to provide their consolidated and updated views on the NCQG as soon as possible, with the aim of drafting a new input document for the third meeting of the Ad Hoc Work Program and the High-Level Ministerial Dialogue on the NCQG, both scheduled for October. These meetings represent the last opportunity to help set the stage for an ambitious outcome at COP29.

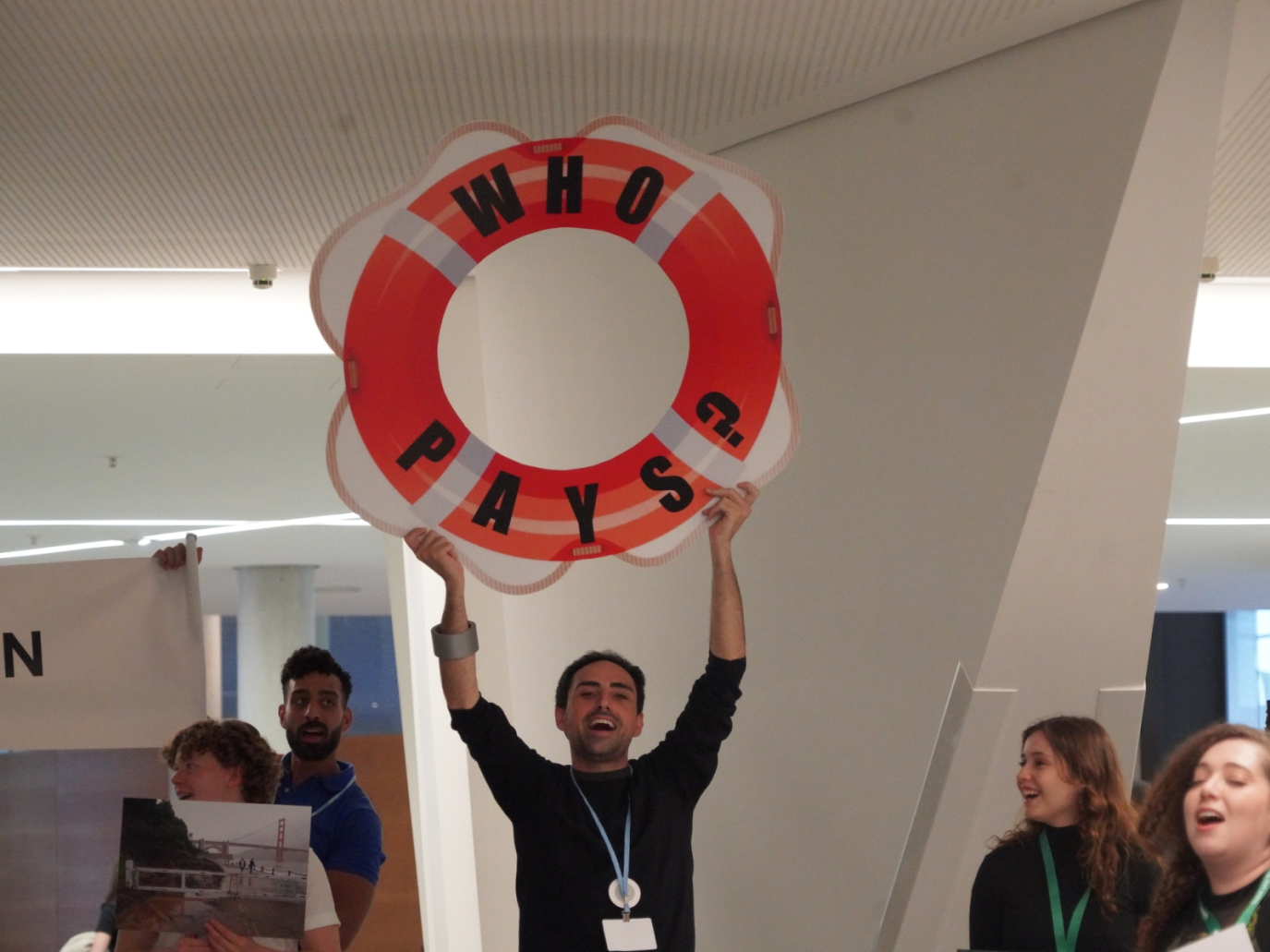

“Rich developed countries talked at length about what they can’t commit to and who else should pay, but failed to assure developing nations on their intent to significantly scale up financial support. Damning silence on what finance might be offered is stymying efforts to raise ambition and is a dereliction of duty to people battling climate-fuelled storms, fires and droughts," commented Tracy Carty of Greenpeace International in a statement. Regardless, the Baku summit chair promised that the New Collective Quantified Goal will see the light of day in November.

Transparency mechanisms: the new features introduced by the Enhanced Transparency Framework

Next we turn to transparency mechanisms, introduced by the UNFCCC in 1992 and later strengthened by the Paris Agreement, which are crucial tools for monitoring countries' progress in fighting climate change and facilitating international cooperation.

These mechanisms are inspired by the principles of equity (according to which all States have an equal responsibility to contribute to the fight against climate change regardless of their material conditions of development) and trust (according to which all States must ensure the transparent sharing of information to foster the establishment of trust among parties). And they materialise in periodic reports that States submit to the UNFCCC. Of these, the most common type is the so-called Biennial Updated Reports (BURs), established at COP24 in Katowice and providing a snapshot of the progress Parties have made in the implementation of their national climate policies.

And precisely on the way the BURs currently work the Bonn negotiations produced some interesting news. Indeed, as part of the Enhanced Transparency Framework, the introduction of Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) was formalized. This is a more comprehensive and exhaustive version of the existing BURs that aims to provide more detailed information on adaptation, mitigation, loss and damage, and climate finance to ensure a 360-degree assessment of individual States' progress toward their climate goals.

Under the new rules, BTRs are to be submitted for the first time by the end of this year by all countries, industrialized and non-industrialized, to the UNFCCC secretariat. Within eight to 10 months of submission, these reports will then be reviewed by a team of experts based on very strict criteria, which can be ascribed to three main assessment techniques: comparison with the guidelines established by the UNFCCC, assessment of the consistency of the information with other data sources, and interviews with national authorities and local stakeholders.

In order to ensure the usefulness and effectiveness of these reporting tools, it seems crucial to provide developing countries with technical support for the preparation and drafting of BTRs, which should ultimately help Parties increase their climate ambition. To facilitate the transfer of technical knowledge and speed up the process, several events were organized during the two weeks of SB60, including the In-person Workshop on ETF Support and the In-session Facilitative Dialogue on ETF Support. The UNFCCC secretariat has since announced that training sessions will continue in the coming months in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean, precisely to enable delegations from countries in the Global South to be prepared for COP29.

Article 6: negotiations on carbon markets and cooperative mechanisms stalled

Even more timid are the progress made in the discussion on the implementation of Article 6, the great unfinished business of the Paris Agreement, even though the subject monopolized the second week of negotiations. If we were to summarize in a few words what this article is about, we could say that it deals with regulating the trade of carbon credits between countries. These exchanges can take place on a bilateral and multilateral basis, following schemes known to insiders as market and non-market mechanisms.

Thanks to a declaration of intent by the Azerbaijan presidency to finalize the "package" of decisions on Article 6 by the next COP29 in Baku, talks initially saw an unexpected acceleration Then came the stalemate. One crux that prevented the talks from continuing was the discussion on "avoided emissions." Not to be confused with "reduced emissions" and "absorbed emissions," avoided emissions are currently a rather controversial element in the climate governance landscape.

Avoided emissions can be defined as the amount of greenhouse gases (mainly CO₂) that is not released into the atmosphere through the adoption of practices or technologies that are deemed "sustainable." Emission avoidance is thus calculated as the difference between the emissions that would have been produced under a business-as-usual scenario and those actually produced. However, at present, there is no international standard or unambiguous terminology for describing avoided emissions, resulting in a lack of uniformity that leaves it up to individual companies to develop their own approaches on an arbitrary basis, leading to problems of accountability.

On the possible inclusion of avoided emissions in the text of Article 6.4 and in the States' national climate plans (NDCs), strong tensions inevitably arose among the Parties, with southern delegations on the one hand expressing concern about the possibility that this could soothe the Paris Agreement's credibility on mitigation, and on the other hand reiterating the need to focus on the implementation of tools aimed at effective, transparent and measurable reductions in climate-altering emissions. Discussions were so heated that the facilitators were forced to resort to so-called "huddles," short informal breaks to allow delegates to brainstorm and find broad agreements before resuming the session.

"SB60's negotiations regarding the Article 6.4 guidelines were rather inconclusive," commented Domenico Vito and Vladislav Malashevskyy, envoys to Bonn for Osservatorio Parigi. "The introduction in the final texts of wording to include emission avoidance within the market for ITMOs created unbridgeable divisions among negotiators, and this despite the fact that there was a moment when it was believed that the preparatory text could make it through to final adoption."

Also still at seaare negotiations on Article 6.8, which recognizes the importance of Non-Market Approaches (NMAs) for implementing NDCs, and which is based on voluntary, noncommercial principles. While it is true that a new online platform designed to collect and exchange information on NMAs to disseminate best practices and facilitate replicability of nonmarket approaches was successfully launched in Bonn, there is still one critical point that has not yet been resolved and that has to do with an exquisitely terminological problem. Currently Parties still do not share an unambiguous definition of NMAs and their positions diverge on which instruments might fall under this category.

While some countries propose the inclusion of mechanisms such as carbon pricing and nature-based solutions within NMAs, others express concern about the risk of confusing them with market-based approaches. Despite the obvious technical and procedural difficulties, which mean that final decisions on this issue will be left to COP29, some States have begun to move. "Several States such as Switzerland, Japan, and Sweden are already signing bilateral agreements with some LDCs, least developed countries, to implement cooperative Article 6 approaches," said the Osservatorio Parigi delegation.

Destination Baku

In short, as pointed out by Simon Stiell's statements, which largely reflect the Global South delegations' frustration, SB60's is far from being a negotiating success. In his view, for it to be called such, the Parties would have had to “get more serious about bridging divides” without assuming that a political agreement will be reached in Baku.

“We’ve left ourselves with a very steep mountain to climb to achieve ambitious outcomes in Baku,” he finally added. Against this backdrop, Stiell also mentioned that outside the UN rooms, there are those who could help build political consensus around points that will be critical in Azerbaijan. The nod is to the G7 leaders, who these days are meeting at the summit hosted in Puglia. Stiell called the heads of state and government of the world's seven strongest economies to responsibility. There is "no time for resting on laurels.”

That's all for now from Bonn. Appointment in Baku, Azerbaijan, for next November.

This article is also available in Italian / Questo articolo è disponibile anche in italiano

Images: Amira Grotendiek © UN Climate Change