To protect 30% of land, oceans, coastal areas, and waterbodies on Earth. To reduce governmental subsidies that are harmful to nature by 500 billion dollars per year. To expand the rights of indigenous communities in protecting the environment. To halve food waste and reduce the risk from fertilisers. To regenerate at least 30% of degraded ecosystems. To mobilise public and private resources worth at least 200 billion dollars a year by 2030.

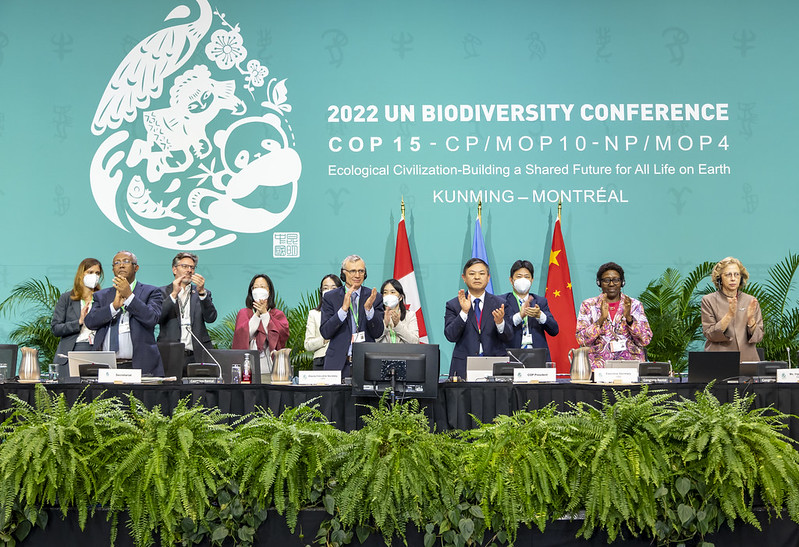

The 15th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, or COP15, has ended with a major achievement: the adoption of the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF). This agreement includes four goals and 23 targets to be achieved by 2030 to stop and reverse biodiversity loss.

The Kunming-Montreal Agreement is a historic result for the protection of biodiversity

The Kunming-Montreal Agreement is the first comprehensive global agreement to guarantee the stability of ecosystem services that are fundamental to human health, economic development, nature conservation (at least 30% of areas protected by 2030 – “30 by 30”), and the fight against climate change. It is a new bulwark to protect against the global environmental crisis.

In an attempt to achieve an agreement more quickly, the Chinese presidency at the conference pushed for a historic agreement but with some watered-down commitments and targets for industry, pesticides, and assessment mechanisms. However, there are many ambitious commitments, with an appropriate financial structure, and several important milestones, such as the recognition of indigenous and local people’s rights to self-determination in the management of natural resources.

“The Global Biodiversity Framework must be a springboard for action by governments, businesses, and society for the transition toward a nature-positive world, in support of climate action and the Sustainable Development Goals,” says Marco Lambertini, Director-General of WWF International.

Resources for biodiversity and harmful subsidies

In terms of the most difficult part of the negotiations – relating to economic resources – a compromise was reached on Sunday night, thanks to the work of the Chinese presidency. This was welcomed by the European Union and other industrialised nations, after days of stalling by developing countries – led by Brazil, Indonesia, and India – demanding more money and the establishment of a new fund.

Firstly, the Global Biodiversity Framework requires the gradual elimination or reform by 2030 of subsidies that harm biodiversity, for a value of 500 billion dollars per year. At the same time, positive incentives for conservation and the sustainable use of biodiversity will increase (Target 18). This specific mention in a UN agreement sets a precedent and paves the way for the inclusion of fossil fuel subsidies in the next climate conference, COP28, where there can be no more excuses. Individual countries must intervene to eliminate these subsidies. Trade agreement management forums, such as NAFTA and, especially, the WTO have to do the same. Last year, the World Trade Organisation already eliminated subsidies for overfishing.

The issue of resources is given ample space (Target 19). By the end of the decade, at least 200 billion dollars per year are to be invested in national and international biodiversity funding from the public and private spheres. Least-developed countries and island nations will also receive support worth at least 20 billion dollars per year by 2025 and 30 billion per year by 2030, through a new Biodiversity Fund that needs to be ready next year as part of the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), an institution that has supported climate and nature investments for decades, channelling resources from OECD countries.

“I am honoured that the Conference of the Parties has asked the GEF to set up a Global Biodiversity Fund as soon as possible,” says Carlos Manuel Rodriguez, CEO and President of the GEF. “The decision also contains a number of important elements in terms of access, competence, predictability, fair governance, and funding from all sources.” Europe has already committed 7 billion euros over the next three years. Germany and France are among the largest contributors, with Italy a notable absence. However, Italian vice-minister Vannia Gava, interviewed by Renewable Matter, promises that “Italy has made a commitment to mobilise resources. We need all sides to come together and commit to doing this. Today we have a unique opportunity to invest in the health of our planet and to put people and nature at the center of our political agenda. Through the Global Biodiversity Framework, we are all making concrete commitments against ecosystem degradation, in the protection of endangered species and initiating transformative actions that integrate biodiversity in all sectors. In this context, Nature-based solutions for climate change mitigation and adaptation are crucial, as well as the conservation and restoration of marine and coastal biodiversity".

Conservation targets

The economic resources brought to the table will serve to achieve the conservation, regeneration, and environmental footprint reduction targets at a global scale in accordance with the Global Biodiversity Framework’s 23 targets. Over the next 7 years, all signatory countries, Italy included, must commit to protecting increasing areas of land, intelligently, reaching 30% by the end of the decade. These could be new protected parks and marine areas, which can also include human activities if they are sustainable. Land use for cementification and useless devastations must cease. Deforestation, the main driver of biodiversity loss, must be stopped. Biodiversity conservation and the regeneration of degraded ecosystems will also be supported via new economic instruments, such as green bonds and biodiversity credits. Projects that combine adaptation and climate mitigation, according to the goals of the Global Biodiversity Framework, will be favoured.

Concerning the regeneration of degraded ecosystems, the text includes an important goal: 30% of degraded terrestrial, aquatic, and marine ecosystems must be restored, or on the road to recovery, by 2030. This is a key message for the managers of large estates, such as large agribusiness corporations, and of major real estate assets, including state property offices.

Meanwhile, there was disappointment regarding the reduction of the environmental footprint of the business world. Without a specific target, measures to reduce the footprint of production and consumption – one of the main drivers of environmental degradation – will be adopted at a national level. “Without national commitments in this sector, the target’s agreements will not be enough to achieve the commendable goal of stopping and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030,” notes Lambertini.

The issue of pesticides also saw negotiations fail to set a target for gradual elimination, with India pushing for the wording to require a “reduction of overall risk”, cutting the use of hazardous chemicals by at least half. Thus, the battle to protect pollinators is still open.

However, other conservation goals were confirmed. The introduction of priority invasive alien species must be prevented and the introduction and establishment of other known or potentially invasive alien species have to be reduced by at least half. Invasive alien species on islands and other priority sites must be eradicated or controlled (Target 6). As a lesson learned from SARS-CoV-2, there needs to be a greater focus on ensuring that the use and trade of wild species happen safely and sustainably, with the aim to reduce pathogen spill-over (Target 5). There must also be a significant increase in the area and quality and connectivity of, access to, and benefits from green and blue spaces in urban and densely populated areas sustainably, by mainstreaming the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and ensuring biodiversity-inclusive urban planning (Target 12).

Biodiversity, what will change for businesses

The Montreal-Kunming Agreement puts renewed pressure on governments but also on the world of business. According to Target 15, countries must “take legal, administrative or policy measures to encourage and enable large and transnational companies and financial institutions to regularly monitor, assess, and transparently disclose their risks, dependencies and impacts on biodiversity,” while also providing information needed to consumers and share information on the use of genetic resources.

With Target 15, “countries have sent a clear message to large companies and financial institutions: get ready to estimate, assess, and disclose your risks, dependencies, and impacts on biodiversity, by 2030 at the latest. Business-as-usual is no longer a possibility,” says Stefania Avanzini, Director of OP2B, a coalition of almost 30 European multinationals. The word “mandatory”, however, is missing from the text. This would have greatly accelerated progress in the agri-food and mining sectors; it would have been a Copernican shift to demand mandatory disclosures from countries on the environmental impacts of their companies, leading financial markets to full maturity.

Then, there is the Pandora’s Box of genetic colonialism, which is the exploitation of the natural wealth and genetic diversity of less industrialised nations that have great biodiversity heritage on the part of multinationals and industrialised countries. Finally, the GBF launches a process on what experts call DSI, Digital Sequencing Information: a fund will be set up, to be finalised by the next round of negotiations in Antalya in 2024, that collects resources deriving from the exploitation of plants and animals in lower-income countries by multinationals in the fields of genetics, cosmetics, and medicine. This is also a major breakthrough, something that seemed unthinkable only a few years ago. We will find out what kind of agreement will be reached over the next two years.

How will progress be monitored?

It would have been better to have a “ratchet-up” mechanism, more resources, and more ambition on the issue of rights. However, the real problem now is implementation and the monitoring of commitments. This is the hardest part.

Reporting systems within the Global Biodiversity Framework are mandatory but not particularly stringent. A new data collection system has been provided, which will be combined with independent scientific research, to be carried out at least every 5 years. It will then fall to the Convention on Biological Diversity to combine the national reports and assess global trends on two distinct occasions: 2026 and 2029, moments of truth that will reveal whether countries are playing their part or have decided to ignore the historic agreement. At this point, it will fall to civil society and businesses to put pressure on governments to keep to their promises.

Biodiversity and human rights

Despite opposition from Russia and Saudi Arabia, the final text, under the Chinese presidency, met the expectations of observers interested in human rights (silencing those who criticised the process as damaging to indigenous communities). The text of the Global Biodiversity Framework requires the guarantee of gender equality in the implementation of the framework, through a gender-focused approach in which women and girls are given equal opportunities and the ability to contribute to the Convention’s three goals (Moscow was opposed to this idea).

Indigenous communities were greatly satisfied by the restating of full representativeness, participation, and disclosure of biodiversity information (namely the participation in the DSI mechanism), full rights over indigenous land, and the full protection of environmental human rights defenders. It is no small thing for Beijing to have signed such an agreement. However, it is still to be seen whether this will lead to improvements domestically.

Framing the Global Biodiversity Framework

While The Guardian, Le Monde, Die Zeit, and the NYT all led with this news on their front pages, even sector-specific media in Italy did not give the issue much coverage. Italy’s minister was absent from the conference and the issue in general did not receive much attention. However, the GBF will have significant consequences on national and local politics, the world of business, and civil society, both in the form of European Directives (EU Environment Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius played a leading role, right up to the end of negotiations) and as national or local initiatives that will see a clear international mandate (can you imagine a moratorium on new skiing facilities in the Alps, with millions of signatories?). Corporate disclosure is a certainty, an unstoppable process, driven by the world of international finance and by NGOs at the same time. Different motivations, same goal.

In short, there is a lot on the plate, a lot to digest, and there will be even more work in understanding the consequences that this major biodiversity agreement will have on nature and the economic and political world. The mandate exists, and it is clear. Civil society and companies are ready to fight to defend it. But without a political focus, the risk of repeating the failure of the Aichi Targets (set for the 2010-2020 decade) is high. While celebrations in Buenos Aires over the football World Cup victory start to wane, the Biodiversity World Cup is only just beginning.

Image: COP15 official