A growing demand for food, raw materials and energy, following land consumption that went beyond the security threshold, has now reached its physical limit. This was the scenario addressed in Berlin during the Global Forum for Food and Agriculture, GFFA, by the Ministers of Agriculture of 62 countries.

Such scenario includes almost all the key issues placing agriculture at the centre of the debate on ethical, social, economic and environmental problems, with its obvious geopolitical implications – suffice to think of the land grabbing phenomenon – whose scope and geographical distribution are still scarcely documented.

Before analysing the outcome of the meeting, the kind of make-up of the participating nations is worth mentioning, as well; Europe is overrepresented, with countries that have little say on the international scene and, by contrast, with major absentees being Brazil, Canada, the United States or some Southeast Asian countries.

But the relevance of the issues on the agenda is unquestionable. Food security is mentioned at the beginning of the final declaration as the main objective to pursue according to The Future We Want declaration signed at the end of the Rio+20 summit. Food security means fighting starvation and malnutrition, thus opposing poverty. Needless to say that the scope of these global emergencies is extremely vast, despite the progress made since 1990 with regard to the reduction of the number of people who have not got enough food (almost an exception amongst the Millennium Development Goals that incidentally are drawing to a close).

While for the agricultural and food industry the GFFA’s final declaration gave a curt response, stating that only a resilient agricultural and food system – diversified and sustainable – can in the end guarantee the right of human beings not only to an adequate nutrition level, but also to the ability of providing for themselves, the main focus was expressed when they stated that agriculture was not only “food & feed”, as it was never the case during all those centuries when mankind’s entire material culture was based on bioresources.

Indeed, the development of the bioeconomy is singled out as a necessary goal to replace nonrenewable resources whose extraction and use are increasingly unsustainable and instrumental in expanding rural areas’ wellbeing and economy, in particular for the most vulnerable shares of the population. To achieve such goal, three main challenges need addressing:

- use of the opportunity deriving from the growth of the bioeconomy;

- guaranteed sustainability and production as well as the use of renewable raw materials;

- guaranteed supremacy of food.

The horizon is that of a sustainable bioeconomy (a term that has gained a broader meaning than the very definition of agricultural activity), characterized by a number of diversified value chains able to play an essential role in determining mankind’s wellbeing by guaranteeing adequate food availability, contributing to the mitigation and adaptation processes against climate change and managing natural resources in a sustainable way.

In plain English, it is about a vision that reinstates agriculture (but it should be borne in mind that the notion of bioeconomy also includes the renewable resources of the seas and oceans) as a crucial sector within the great global sectors, whose implementation must go through a convergence of objectives and strategies amongst economic, social and environmental sustainability. Of course, the issue is how to achieve it.

In this regard, the recommendations contained in the document are a reminder that when it comes to agricultural resources there is a discourse that “eats up” all the others, namely that of starvation, of food scarcity and deprivation. This is partly a paradox because as things stand there is not an authoritative source supporting the fact that the current production capacity of the agriculture and food system is incapable of feeding the population of our planet and that the real problems may be called something else: poverty, accessibility and distribution, dumping, protectionism... Such tendency often leads to envelop the bioeconomy question in a number of precautions, mitigations and explanations.

But the opportunities potentially offered by the development of an economy increasingly based on renewable resources clearly emerge. The value chains, made through the bioeconomy generate new jobs while consolidating existing employment, create added income and allow access to promising markets. This involves all economies, ranging from the most advanced to the emerging or the developing ones.

In particular, it is worth noting how in countries with little fossil resources but endowed with vast forest or agricultural assets, the development of a biobased industry can represent an opportunity to increase the added value of the agricultural production.

Promotion of integrated systems combining resource production for food and non-food sectors, so as to diversify income sources while strengthening resilience, development of sustainable markets for bio-based products, enhance research particularly in the possible synergy or trade off effects between the production of renewable resources for food and non-food sectors, response to socioeconomic problems, including those of small owners and young farmers. All this through the adoption of solutions and strategies adapted to various local conditions. This is also another significant step that indirectly questions the land grabbing activity and more generally the dynamics of global markets of forest and agricultural products.

Besides the local aspect characterizing the bioeconomy’s models, the other important pillar they stand on is their sustainability. This must be guaranteed through the dissemination of suitable production practices, aimed at a sustainable management of resources and greater protection against the risks of climate change, by transferring technologies and implementing voluntary standards and certifications, providing there is a consensus. And last but not least, by raising awareness of consumers with regard to bio-based sustainable products.

A reminder of “food supremacy” is mentioned again at the end of the document, with a series of predictable recommendations reiterating the above-mentioned concepts, referring to what will be discussed at Expo 2015. How the Charter of Milan – the document which should be ratified by the participating countries at the end of the event, will pay attention to the prospects highlighted by the GFFA – remains to be seen.

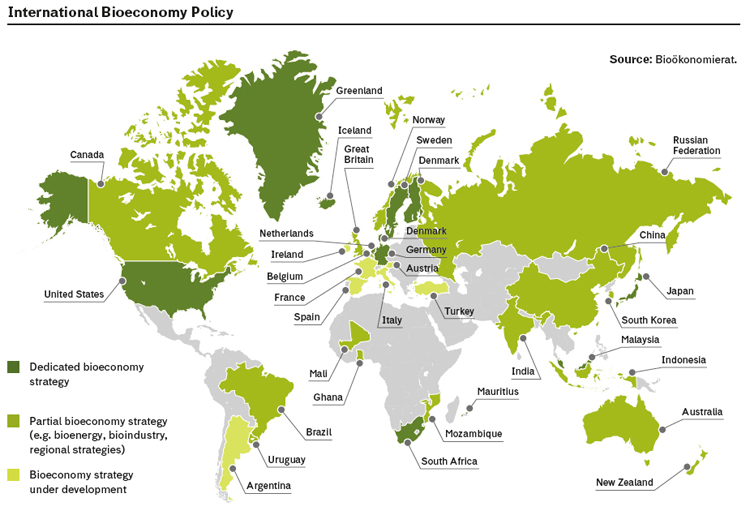

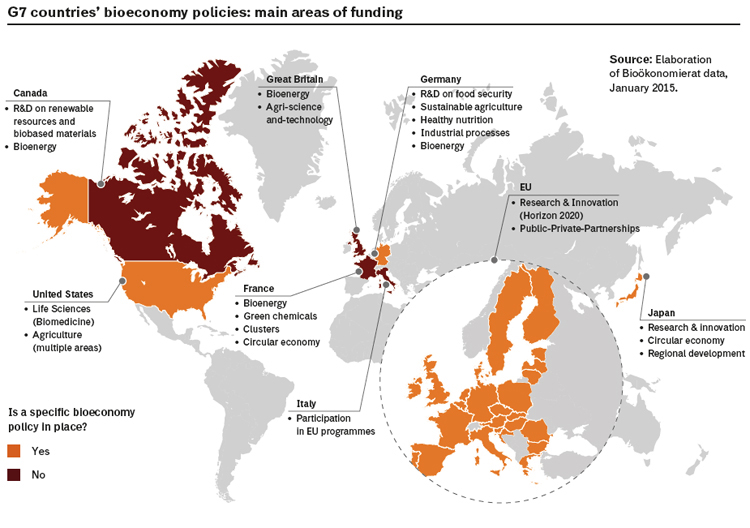

Meanwhile, another recent study conducted by Bioökonomierat in Berlin (the Bioeconomy Council of the German Federal Government) analyses the viability of the vision proposed in the GFFA’s final declaration, where the strategies for the bioeconomy in the G7 is analysed.

Besides confirming the consolidation of a vision where agriculture does not only entail food, feed or biofuel – where the idea of the cascade use of renewable resources has reached wide consensus – the situation is a mix of top-down and bottom-up strategies. It is not a homogeneous picture, not least because of the endowment of bioresources of the various nations. The US and Canada, two bioresources super powers adopt different strategies that – it is quite safe to say – stem from the political orientation of the two federal countries. While within the European Union there are significant differences (there are those who direct their efforts to innovation of their own industrial sector and those concentrating on network building, trying to coordinate their policies with other countries), countries with scarce raw materials such as Japan feel the need to devise a national strategy in this regard.

In general, considering the bioeconomy no longer as a promising research sector, but rather as an important component of strategies for innovation and industrial development with substantial elements of growth and sustainability, has gained consensus.

The identity of what the bioeconomy is now and will be in the future is therefore emerging: a key element of an economy looking more and more closely at a sustainable use of resources.

Its potential ranges from bulk chemicals to innovative materials such as polymers or bio-based fibers, applicable to products with a highly sustainable life cycle.

Moreover, the development of bio-based products acknowledges the growing demand for natural, healthy and sustainable products.

By way of conclusion, the Bioökonomierat Study states that so far it has not been possible to ascertain if adopting a strong top-down coordinated effort is more productive than leaving the single industrial sectors to act on their initiative. Undoubtedly, the resources on which these new sectors base their development limit the technological advantage of the industrialized countries over emerging ones, richer in bio-based resources.

Gaps are closing and a new global economic geography is being outlined. Countries rich in raw materials such as Malaysia, Brazil, China, India, South Africa and Russia can become suppliers of end products.

Once again they state, “the bioeconomy is acting as a strategy for growth or for industrial regeneration.”

And what about Italy? Italy is amongst those who rely totally on the ability of companies to renovate. There is significant resistance from those sectors who regard the development of an advanced bio-based economy as a kind of threat.

But, of course, this aspect is omitted in the Bioökonomierat Study.

For an update on the subject: video interview with Lester Brown “Crop yields can’t be increased anymore: world hunger imminent”, tinyurl.com/lwas8ud

Global Forum for Food and Agriculture 2015 final communiqué, The Growing Demand For Food, Raw Materials and Energy: Opportunities for Agriculture, Challenges for Food Security: tinyurl.com/omsv4t4

The Future We Want, tinyurl.com/czenz9g

Millennium Development Goals: 2014 Progress Chart, tinyurl.com/mn9nzqd

For further information on Charter of Milan please consult: tinyurl.com/ndergsl

Bioökonomierat Study, Synopsis and Analysis of Strategies in the G7: tinyurl.com/nk7lx8v