This article is also available in Italian / Questo articolo è disponibile anche in italiano

Azerbaijan, the host country of the COP29 climate conference in Baku, is certainly not a positive player in the energy transition, nor is it a country notable for democracy and liberal openness. However, after the Ukraine invasion, and the consequent reduction to minimum levels of oil and gas imports from Russia, Italy radically reorganized its supply sources, among other places strongly wagering (in addition to Algeria) on Azerbaijan itself.

And, according to a study by the climate think tank ECCO, released just on the opening morning of COP29, Azerbaijan allocates 57 percent of its oil exports to Italy, which is the main outlet market for Azerbaijani oil. On the gas front, it exports about 20 percent of its production to Italy, positioning it as the second-largest gas supplier to Italy after Algeria.

A dependence that, according to the research - supported by analysis by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) − is likely to create significant repercussions in the future. Firstly, for Azerbaijan itself, which is an economy heavily dependent on oil and gas exports, and which very soon will have to deal with a European demand that is bound to decrease between now and 2030. This therefore will not justify new infrastructure investments. There are, however, also risks for Italy, which could commit significant resources − including public, through its fossil-sector subsidiaries − to pipelines and works that will be stranded assets, that is, whose costs are unlikely to be repaid.

Oil and gas, the prospects for Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan can rightly be referred to as a “petrostate.” As of today, in fact, fossil fuels account for more than 90 percent of its export earnings, 60 percent of government revenue, and 35 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). 95 percent of Azerbaijan's exports are oil and natural gas, and European Union countries, primarily Italy, account for more than half of the country's total exports. According to ECCO's study, however, no stable demand conditions emerge in the European gas market to justify new infrastructure investments in addition to limited availability of Azerbaijani gas supply volume.

The increase in Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) transport capacity, which is expected to rise from a capacity of 10 to 20 billion cubic meters per year, does not seem warranted within scenarios that see Italy and Europe pursuing a path consistent with national and European climate goals to 2030, as well as the international commitments of the Paris Agreement. The scenarios in the report The State of Gas, and specifically the Fit-for-55 decarbonization scenario built on a gas demand as given by the National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (NECPs), show how the existing infrastructure can already cover the required consumption volumes, and even ensure Italy's export volume of more than 7 billion cubic meters per year.

Regarding supply, however, according to a study by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES), by 2030, under the assumption of the lowest plausible level of Azerbaijani gas production and with domestic demand remaining stable, there would be no residual volumes of gas available for export to Turkey and European partners. If the maximum plausible level of production is assumed instead, a total of at most 15 billion cubic meters per year of incremental gas could be available by 2030 in addition to the volumes already contracted. This estimate could decline again by 2035 due to the natural decline of the deposit.

In sum, ECCO's analysis concludes, Italy should consider three aspects in its political and economic relations with Azerbaijan. First, betting on gas means risking generating investments that will be lost once they are no longer profitable. In this respect, investments by major investee companies would also involve and put public capital at risk. Second, it reads, setting a gas-focused report without providing measures to support economic diversification means condemning the country to a future of uncertain and risky revenues, with repercussions for the exporter's budget sustainability and economic health. Finally, Italy, as the first trading partner, should champion measures that can accompany Azerbaijan's process of economic diversification: for example, through the activation of new forms of economic and industrial diplomacy for the identification of zero-emission projects that can foster the development of alternative sectors to oil and long-term planning.

What risks does Italy face?

These considerations are only partially supported by Massimo Nicolazzi, an in-depth industry insider with nearly 35 years of experience in the hydrocarbon world. Nicolazzi worked for Eni and Lukoil before being appointed managing director of Centrex Europe, he is a freelance energy consultant, senior advisor to ISPI's Energy Security Program and professor of economics of energy sources at the University of Turin, as well as a member of the scientific committee of the geopolitical magazine Limes. The first topic the professor highlights is that, from Italy's perspective, we cannot realistically talk about our country's energy dependence on Azerbaijan. “About a third of the gas that comes to Italy from Algeria comes from that country,” he explains, “and if we want to discuss gas in general, the biggest supplier to Europe this year was the U.S., through liquefied natural gas. Certainly, we can expand the infrastructure that brings us the Azerbaijani gas from over there, but it will still be a reasonably limited share of Italian consumption.”

When thinking about the political aspects, however, considering the certainly not exemplary democratic record of the immovable President Ilham Aliyev who succeeded his father Heydar Aliyev, is it not a danger for Italy to put itself in the hands of another authoritarian leader, moreover engaged in a military and diplomatic conflict with Armenia over Nagorno Karabakh? “All scenarios are always possible: just consider that for a couple of weeks in 1914 after the murder of the Austrian Archduke in Sarajevo no one thought war was likely,” is Nicolazzi's retort. “But I hardly see any risk to Italy's supplies. A country like Azerbaijan, which has a heavy dependence on oil revenue, may temporarily suspend supplies, yet then for anyone governing, the export of hydrocarbons is the first element of cash for welfare, social spending, investment and domestic budget.”

The ECCO study recalls how the government's National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) calls for a doubling of the capacity of TAP, the pipeline linking the Balkans to Italy under the Adriatic Sea. In prospect as of 2026, there will be more gas import capacity, but there will also need to be an upgrading of the network of methane pipelines connecting TAP to the Adriatic line. Do they risk being unprofitable investments, soon rendered useless by declining gas demand? “My premise is that as the post-2022 world scenario has shown, the only form of energy security that we have been able to develop so far is redundancy, with strategic oil and gas stocks,” Nicolazzi replies.

According to the expert, “some redundancy is useful, especially if it is carried out with venture capital from private companies. It's one thing if the state, and therefore taxpayers, were to finance this infrastructure. But if someone is willing to take the risk of investing in what could become a stranded asset, let them.” What about state-owned enterprises, such as Eni and Snam? “It seems to me that they distribute profits,” is the conclusion.

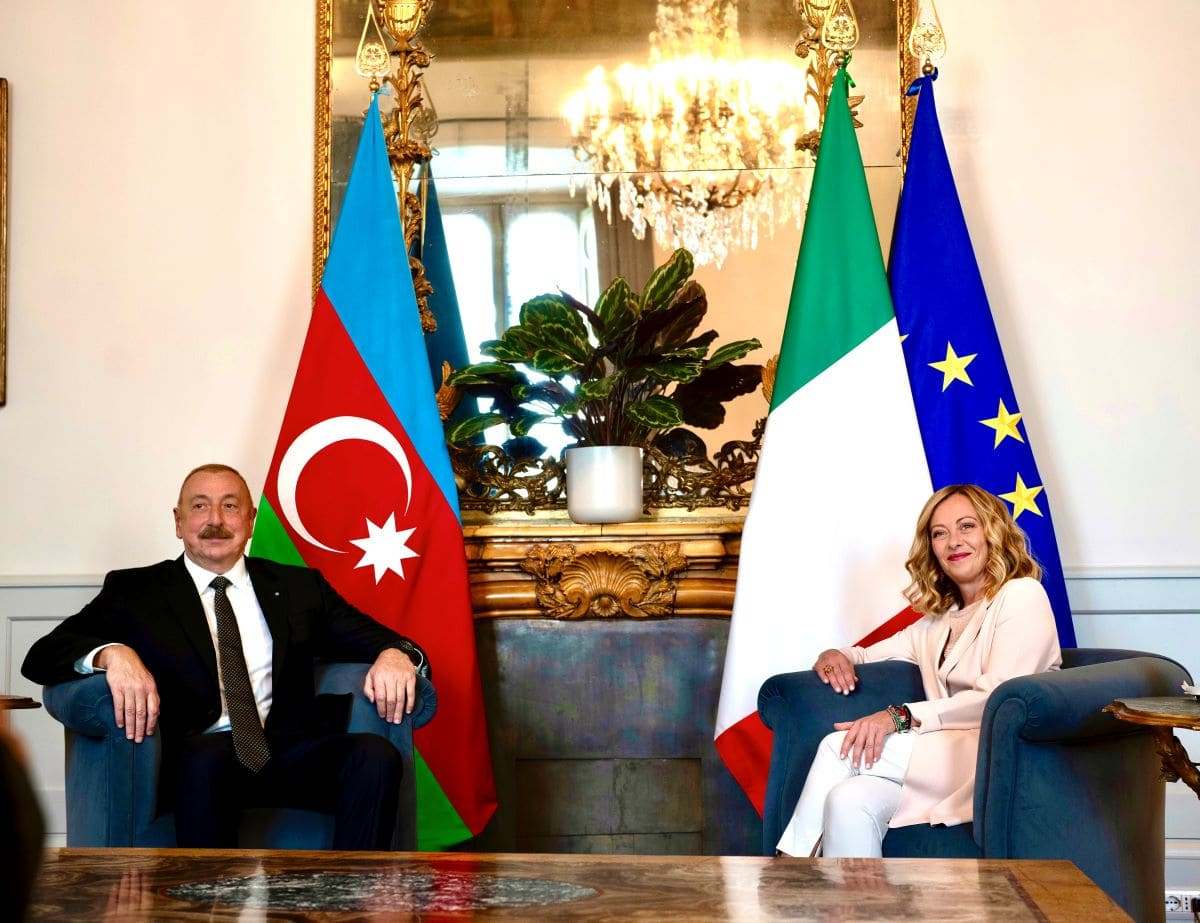

Image: Giorgia Meloni and Ilham Aliyev © Palazzo Chigi