Photography: Fausto Podavini

Research: Marirosa Iannelli

Top image: Witbank. In a coal mine a woman collects coal for personal use. Coal is the only resource for locals.

“Do you know what it means to be close to a power plant? Being close to trouble.” Tiger B., is 41 years old, though he seems sixty. He has always worked as a welder in the coal-fired power plant, Duvha Power Station, near Emalahleni. It’s an appropriate name for a mining city: in the Nguni language “Emalahleni” means “place of coal.”

His life and that of his family’s are in harmony with the rhythm of the 3,600 Megawatt power plant. The owner of the plant is Eskom, the state-owned electricity utility company and for years now the largest in South Africa. The coal mine feeds energy production, and black smog covers both the village and also Tiger’s lungs, which are clogged with phlegm and dust. “Do you see the high-voltage cables and water pipes? They are for the power plant. But in the village we have neither electricity nor water. Hundreds of thousands of litres per minute are used to cool the turbines that generate energy sold to Swaziland and Mozambique. For us, we live in the dark and get three and a half litres of water per day that we carry in a tank.” In the makeshift village, almost 5,000 people live stacked beside a coal wall and a black water well, waiting every week for the small community cistern to be filled. “People often argue furiously for a few more litres,” says Lucky, who prefers not to use his full name for fear of retaliation, passing a dirty cigarette to Tiger. “Coal is stealing our right to water and air.”

|

|

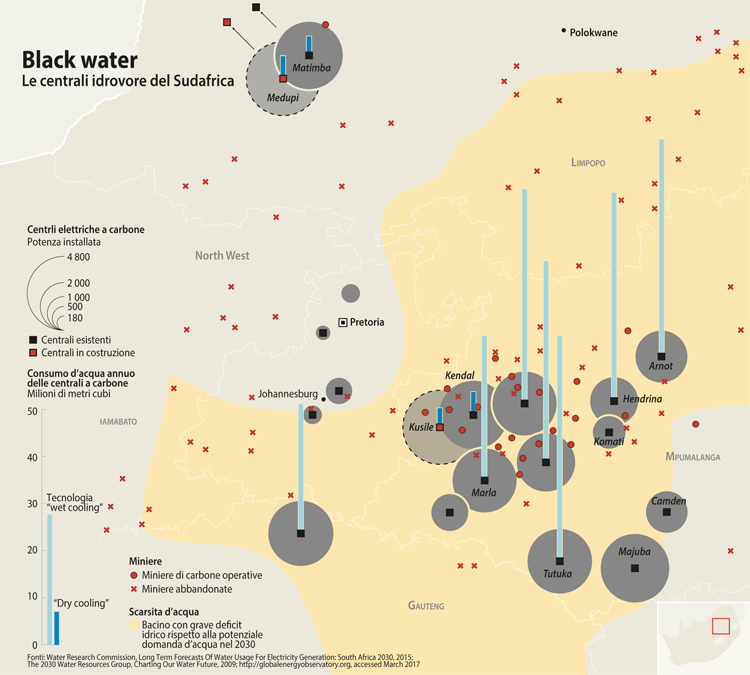

Graphics: Riccardo Pravettoni and Federica Fragapane Source: Water Research Commission, Long Term Forecasts Of Water Usage For Electricity Generation: South Africa 2030, 2015; The 2030 Water Resources Group, Charting Our Water Future, 2009; globalenergyobservatory.org, accessed March 2017.

|

South Africa and water

The country of Nelson Mandela and Kruger National Park, the last preserve for lions and rhinos, has in recent years become one of the least sustainable countries on the African continent. The main offender is the mining industry, which accounts for about 8.3 percent of the country’s GDP. South Africa extracts 8 million carats of diamonds each year, owns more than 80 percent of platinum and 12 percent of the world’s gold. Both are extracted from giant South African mines, the largest over 3,900 meters deep. But on the throne of the most impactful materials “given” by the Earth, sits coal. Coal is the main culprit for global warming (South Africa ranks thirteenth for CO2 emissions) and water use, consuming around 10 percent of the country’s total.

South Africa possesses 3.5 percent of global coal reserves but accounts for over 6 percent of global exports. The coal that remains feeds 81 percent of electricity production, which is controlled almost entirely by the state-owned power utility, Eskom.

Coal has an extremely heavy water cost: each ton extracted requires over 10,000 liters of water. Large power plants, such as the one in Kusile, opening in 2017 near Maheleni, will use 71 million liters of water per day. Consumption is similar at the Duvha plant, home to Tiger and Lucky.

|

|

Witbank. Aerial view of the Duvha Power Plant of Eskom, the second biggest power plant of the whole Africa. Eskos is a South African electricity public utility, established in 1923 as the Electricity Supply Commission (ESC) by the government of the Union of South Africa in terms of the Electricity Act.

|

“South Africa is a dry country, with only 490 millimeters of precipitation each year. Shortages of water for domestic use are characteristic of the country. Yet the economy is structured as if there is a lot of water,” explains Stephen Law, director of Environmental Monitoring Group, a group of environmental analysts based in Cape Town. “Seventy-five percent of water resources are already completely booked, and no water for daily use remains. According to our projections, by 2030 the country will have a 17 percent water deficit. That means that many people will go without water, especially the poorest. How does all this coal make sense?”

“The battle for water is a battle for rights,” says Kumi Naidoo, ex-director of Greenpeace and now an environmental activist in South Africa. “Jacob Zuma’s government uses the logic that investing in coal creates job and economic development. Actually, no miner wants his son to do his job. And nobody wants to be deprived of breathable air and drinking water. South Africa can create new jobs in renewable energies, like solar and wind energy.”

For now, coal is king. The industry is worth $22 billion, according to data from the Chamber of Mines, the promotional organization for mining companies. President Zuma’s family – his son Duduzane – is involved in the coal business. “No one in Pretoria will do anything to stop coal. The interests are too high and they are all involved,” continues Naidoo. Under pressure from citizens and environmentalists, mining companies such as Anglo-American and Exxaro have begun implementing sustainability policies to reduce water consumption for dust suppression and to minimize impacts on the environment of mines at the end of life. Even Eskom, the leading producer of South African electricity that controls 95 percent of the market, is trying to reduce water impacts.

According to Eskom’s spokesman, the company has decreased its water use by virtually half: from 2.85 l/kWh in 1980 to 1.44 l/kWh in 2015. “It is important to note that Medupi, similar to its sister power station Matimba nearby, uses direct dry-cooling technology, meaning that it uses air for cooling purposes and thereby uses less water in the process. The choice of dry-cooled technology for Matimba and Medupi was largely influenced by the scarcity of water in the area. Both stations use a closed-circuit cooling technology similar to the radiator and fan system used in motor vehicles. Water consumption is in the order of 0.1 litres per kWh of electricity sent out, compared with about 1.9 litres on average for the wet-cooled stations,” explains Eskom’s spokesman, Khulu Phasiwe, via email. Attention is also given to supply: to ensure water supply in the Waterberg region where the Medupi Power Station is located, Eskom will construct a pipeline from the Crocodile river at Thabazimbi. Excess water exists in the Crocodile River catchment area due to the high return flows from treated effluent from sewage treatment plants in Guateng.

“These are only cosmetic operations,” contends Dean Muruve, WWF South Africa’s Water Source Area Programme Manager, in his Johannesburg office. “When a real water crisis comes, we will find ourselves simultaneously facing an energy crisis because the mega-power stations will have to be turned off. Coal should stay in the ground and we should favor use of renewable energies.”

|

|

Witbank. Inside a coal mine, a woman is picking coal that she’ll take to her family and that it will be used to cook. As there’s no electricity, coal is the only means to cook.

|

Little and Poor Quality

In the villages of Coronation and Driewater, two slums on the outskirts of Emalahleni, stands a Dickensian landscape: mountains of coal, dusty slums immersed in black smog from heavy vehicles used for extraction, fine black dust and rocks with white crust formed from acid mine drainage. Smoke even spools from underground, where coal from an old, abandoned mine burns slowly by spontaneous combustion. The smell of sulfur infests the huts huddled around the steaming coal mountains. The water available is scarce and often undrinkable. Nearby are twenty-two mines – many already exhausted. It is impossible to think that this is a healthy place.

Willonah Noudo Kubeka, 33, is on dialysis for kidney malfunction. “I don’t drink water anymore, only juice. Water’s drinkability here is uncertain.” Willonah is one of many residents with health problems related to the mining industry and water contamination. In some areas water toxicity is higher than any recommended levels. “We have measured the pH of water discharged from the mine,” says Rudolph Sambo, a young activist from Emalaheleni who works to generate awareness of the health risks related to water among the miners. The result? The water is highly acidic, with a pH lower than 2.2. “You can’t drink it, you can’t irrigate, you cannot even wash in it. Anyone who does runs the risk of skin, kidney or liver diseases.” Medical data does not exist. In Emalaheleni hospitals the doctors interviewed speak of diseases, but prefer not to give figures. Despite several requests of data from the Health Department of the Nkangala district, no reply has been received to-date.

“On paper, we have good regulations in South Africa. The problem is implementation, which is nonexistent. Several water treatment plants are either in partial or total noncompliance. Many mining companies, especially smaller ones, extract without any water controls at all,” illustrates Stephen Law, pulling out papers and documents. “Just look at acid mine drainage, which is becoming increasingly common and critical.” In Africa the intense mining activity has caused abundant runoff of minerals and metals that react with water to contaminate it and make it corrosive. The effects on aquatic environments, drinking water and infrastructure are devastating. “The problem,” continues Law, “is that the more water is used for extraction, the less of a chance that the acids will be diluted. Not to mention the piece that closes the circle: more coal means more emissions, which means significant impacts on climate and less rainfall. A perfect storm is brewing in South Africa.”

|

|

In one of the shopping centres near Witbank built thanks to the profits of investments in coal. Two women study current offers. Shopping centres are the only recreational areas for Witbank, a truly industrial town.

|

Assault on the Environment

Multinational and small, local mining companies alike seem little interested in water issues. Stimulated by a laissez-faire government, they are pushing for development into unexplored areas, in particular those of the Limpopo region. Like the Waterberg Project, with 8,000 hectares of platinum extraction, or Makhado, a new mine of 5.5 million tons of coal developed by Coal of Africa Ltd.

One of the areas lesser known to the media – and to investors – is the southern area of Mpumalanga, on the border with the state of Kwalazulu-Natal. Ahta-African Ventures, Ltd., part of Atha Indian Group, has submitted a request to the Ministry of Mineral Resources to create a mine in the heart of a protected area, the Mabola Protected Environment, according to documents obtained by the author. A desert ready to be exploited? Not at all, the Mabola is a critical wetland at the confluence of three water reservoirs: the Vaal, the Tugela and the Pongola. The area is part of a strategically important system of protected areas. The territory covers eight percent of the nation’s total area, but collects 50 percent of all precipitation.

|

|

Witbank. In a mine. A digger excavates the soil to extract coal.

|

Oubaas Malan, a sixty-six year old man with dry, white legs covered by pair of khaki shorts, leans on his Toyota pickup. He watches from a distance his 3,000 sheep grazing in a valley, green from December’s rains. The air is fresh, the hills perfumed by chlorophyll. A jeep of tourists armed with binoculars and professional 700 mm telephoto lenses move slowly along the dirt road, hoping to spot rare birds like a Blue crane, Rudd’s lark, or the rare bald ibis. A group of boys walk barefoot in the pastures, on ground still soft from last night’s rain. “The mine will be built exactly here,” he says, pointing to the valley, “and I will have to leave. The water for the cows will be at risk. I have a friend who had cows near a mine and they all got sick,” says Oubaas, in an English heavily marked by a strong Afrikaans accent.

The local population is against the project. In case of an accident or acid drainage from the mine, not only the valley but also the entire area would be affected. The mine would be at the highest point of the triple reservoir.

“The mine threatens to devastate this area,” explains Andrea Weiss of WWF South Africa. “This would not only impact biodiversity, but also local tourism at Wakkerstroom, which is strongly focused on eco-friendly trips and bird-watching.”

These are some of the reasons why environmentalists are up in arms. “This area is protected, classified by the South African National Biodiversity Institute as one of the twenty-one strategic water resources,” explains Melissa Fourie, executive director of the CER, the center for environmental rights in Johannesburg. “We cannot allow Atha to win this legal battle.” Stopping the Mabola mine does not mean being hostile to coal production, but, as Andrea Weiss explains, “it means deflecting the thirst of mining companies towards less vulnerable areas and areas les central to water security. Moreover, the country should implement a coordinated strategy to avoid harmful impacts of acid drainage and contamination of resources for agricultural and human use.” A verdict on Mabola is expected this summer.

|

|

Witbank. A man crossed a small bridge that divides the the area on the coal mine near the Duvha Power Plant and the township where many workers of the power plant live.

|

New energy, new water crisis

If the battle over coal seems already destined for a lengthy conflict, two new challenges are emerging to further complicate the confrontation between water security and national energy development. The affected area is southern Karoo, a desert area in the heart of the country – the mining provinces. According to prospectors, under the rocks of the sunburned Karoo are significant uranium mines, which are essential to support the renewed and controversial South African nuclear program. There are also important shale gas resources, an unconventional natural gas extracted by fracking, which means fracturing the rock under the surface using water and chemical agents at high pressure. According to think tank Transnational Institute, fracking is considered “a system that is seriously jeopardizing the community and causing a troubling diversion of water use in favor of mining companies.”

At present, an environmental campaign begun in 2011, Unearthed, by Jolynn Mynnaar, has put a temporary stop to developing shale gas extraction. The prospect of nuclear energy and uranium mining, however, continues. The government is set to invest more than 70 billion with Russia’s Rosatom for a new nuclear power plant. The plan is the daughter of an agreement between Russian President Vladimir Putin and his African counterpart, Jacob Zuma. The project has stirred up mining companies to file mining claims related to uranium, including in the Southern Karoo.

|

|

Witbank. Inside one of the townships. A woman checks backlights the deposit of heavy materials in the water she took in a fountain present in the township. In later years, coal mining made water highly polluted. In this area, water is used to extract the coal.

|

“It’s madness,” said Bill Steenkamp, while parked in a desert valley just outside Beaufort West, in the heart of Karoo. The temperature rises to 37 degrees Celsius, the heat blurring the horizon, altering the light’s trajectory. “There is no water in Karoo. You can see it with your own eyes. To extract uranium water will be imported by train from the coast, while taking advantage of every drop that we have here now. The companies interested have already done their numbers. In the region the population uses 7 billion gallons of water a year. The uranium operations alone would require 14 billion liters. Maybe the water is coming from the coast, but what happens if they contaminate the few reserves of fresh water we have here with radioactive elements?” Climate change has already made its mark. Precipitation has been dangerously low for the past few years, and for years many basins around Beaufort West, one of the main urban centers of southern Karoo, have remained dry.

In Beaufort West unemployment exceeds 40 percent. For many, the new mining boom could be an opportunity to get out of poverty. “They should be investing in solar and wind energy. There’s plenty of wind and sun here,” says Bill kicking the dust with his shoe to emphasize the northern breeze. “As long as they stop continuing to dig in this poor country.”

|

|

Witbank. In one of the many townships of Witbank, near a depleted coal mine. Kantigi waits for the coal to turn into ember in order to use it to cook. In the township one can use only coal to cook or to get warm and it can be found, in small quantity, in the depleted coal mine.

|