Wachstum und Stabilität. Germany has based its economy on this formula since the Weimar Republic period. Growth and stability for a country that for years has been recognized as the driving force of the European economy and that today is determined to establish itself also in the bioeconomy sector through a strategy and teamwork involving businesses, universities, research centres and institutions. Of course, the Dieselgate that hit Volkswagen could be very costly for the whole German industrial sector. It is a hard blow for a country that has always been proud of its reliability and runs the risk of becoming a burden for the future development of the bioeconomy, above all as Manfred Kircher, Clib2021 Cluster Advisory Board, stated, “in terms of authorities and public opinion’s perceived reliability.” But it could also have a positive effect, for example boosting the growth of advanced biofuels. At least, this is what is envisaged by Hariolf Kottmann, CEO of Clariant, the Bavarian chemical colossus that produces biofuels from agricultural waste.

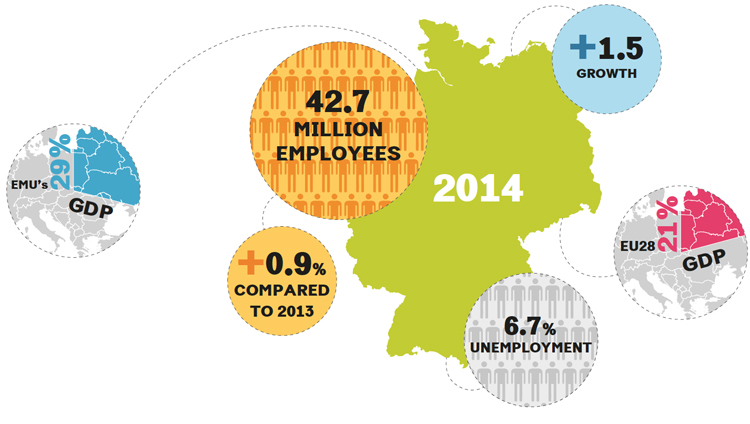

Figures speak for themselves: Germany’s GDP represents 29% of the total monetary Union’s GDP and 21% of that of EU28, with a growth rate of 1.5% in 2014. As for public finances, 2014 ended with the second best budget surplus since reunification, about €12 billion. As a consequence, the job market keeps sending very healthy signals, representing a stabilizing factor for the economy: in 2014 employment reached the highest level in the last eight years, 42.7 million workers (+0.9% compared to 2013) with an unemployment rate of 6.7% (February 2014).

Germany is the richest and most industrialized country in Europe. It looks to the future with strength and vision, copied by many other European governments. Its industry keeps innovating, collaborating with universities and vice versa. “In Germany, the opposition between science and philosophy,” the great Italian historian Carlo M. Cipolla wrote, “was solved in the 19th century with Technische Hochschulen (Technical Universities),” creating characters such as Franz von Baader, the Munich mining engineer whose philosophical works influenced Friedrich Schelling’s philosophy of nature. Or Rudolph Diesel, the inventor of the eponymous engine protagonist of the Dieselgate, also known for his internationalism.

In 2010, long before the European bioeconomy strategy was announced (February 2012), Berlin allocated €2.4 billion to fund bioeconomy R&D until 2016 within its “Bioeconomy 2030 National Research Strategy” that laid the foundations for a change both in society and in the industrial sector based on the use of biological resources. Teamwork that involved the Ministry of Research, Food and Agriculture, Economics and Technology, the Environment, Economic Development, Health and Internal Affairs with the awareness that the bioeconomy as a meta-sector requires a holistic strategic vision.

An example? Using research funds to stimulate greater sustainability in agriculture through soil protection and preservation. Furthermore, supporting within the Strategy “Biotechnology 2020+” new forms of cooperation between life sciences and engineering to create the bio-based products of the future.

The collaboration between the Ministry of Research and the Ministry of Food and Agriculture, promoted by the creation in 2009 of the Council for the Bioeconomy as an independent advisory body led to the definition of a biorefinery roadmap in Germany, offering a very accurate representation of the most important technologies for using renewable resources for energy production and industrial purposes, and identifying at the same time the main obstacles and what is needed to implement suitable research policies.

In summer 2013, the Federal Government led by Angela Merkel presented its National Political Strategy for the Bioeconomy, with which it defined “objectives, strategic approaches and measures to fully exploit the useful potential to create added value and employment as part of sustainable management and to support a structural change towards the bioeconomy.” The Council is now assisted by an interdepartmental working group, a control room for the development of policies on research, innovation, industry, energy, agriculture, the environment and climate change able to make Germany competitive internationally.

The national strategy was followed by regional measures that put the bioeconomy at the heart of research funding. And the bioeconomy has become the focal point of research carried out by universities and institutions such as the Helmholtz Association, the Leibniz Association, the Max Planck Society and The Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft.

So, is it all a bed of roses? Obviously not. “It is true,” a manager of a great German company complains, “that we have planning and a vision, but then institutions waste a lot of time in implementing effective policies for the sector. For instance, we are still waiting for a law such as the Italian one banning plastic bags, despite being discussed for years. In the end, what really matters is the power relations between the industry using fossil resources and that using bio-based resources.”

Anyway, the Ministry of Research portrays Germany as a bioeconomy hub and funds are allocated with priority to the “bioeconomy as social change” within a framework called “Research for sustainability” based on four pillars: transforming research into technological innovation, developing social monitoring, promoting junior research groups, funding interdisciplinary research groups on social, economic and related scientific topics. Once again, a holist approach aiming at grouping together all the prominent actors of the innovation chain through platforms and networks that promote knowledge and expertise sharing: small and medium-sized enterprises, large industrial groups, universities, research centres, clusters, farmers but also consumers, investors and certifying bodies. This collaboration is made possible by “Innovation Alliances”, strategic cooperation forms between science and business focusing on areas of specific application or on markets of the future. They aim to create investment leverage committing businesses to a long term investment of €5 for each euro for research they obtain from the Federal Government.

Clusters are a symbol of this German collaboration system. Germany has the only cluster in Europe that directly mentions the bioeconomy, the BioEconomy cluster in Halle grouping a wide variety of academic and industrial actors from different sectors integrating them in a chemical hub already established in the area. The Leuna industrial park is the biggest chemical centre in Germany and the first demonstration biorefineries were built here.

While Clib2021, based in Düsseldorf (North Rhine-Westphalia), focuses on industrial biotechnologies and combines both interdepartmental and across-the-border value chains, 30% of its members are based outside Germany.

The Driving Role of the Chemical Industry

The chemical industry is the driving force behind the German bioeconomy, sharing the objective of gradually getting away from using fossil resources and oil price volatility but above all reducing greenhouse gas emissions. According to data provided by VCI trade Association, in 2013, Germany, for its turnover, was the fourth global market for chemical products, overtaken only by China, the USA and Japan. It is by far the first European market; its share (about €200 billion) exceeds 25% of the total turnover. At global level, it is the first exporter of chemical products: with €160 billion in 2013, it overtook the USA, Belgium and China. In the same year, investments in R&D activities reached €11 billion (up from 8 in 2010). Germany has the largest chemical manufacturer in the world, BASF with a global turnover of €74.326 billion in 2014. But Germany also has Bayer (42.239 billion), Henkel (16.428), Evonik (12.917), Merck (11.501) and Lanxess (8.006).

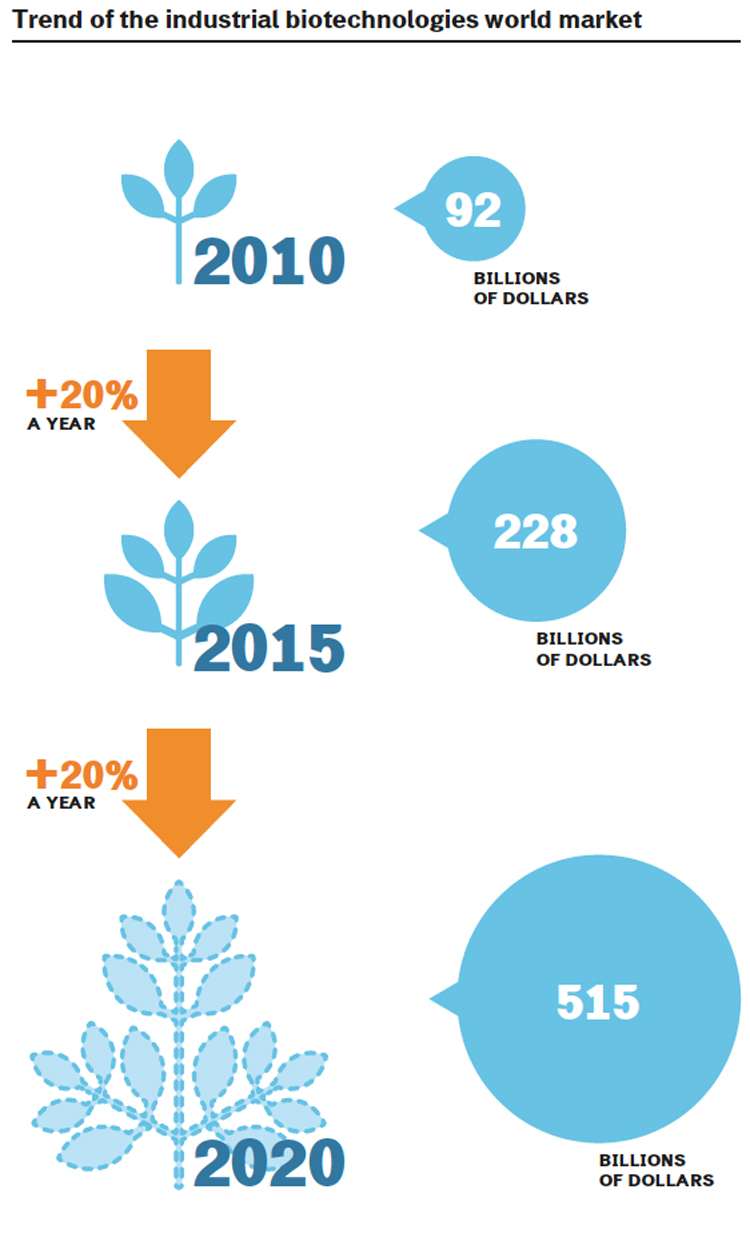

According to Gunter Festel, founder and CEO of Festel Capital, the global market of chemical products derived from using industrial biotechnologies is destined to grow from $92 billion in 2010 to 228 billion in 2015, reaching 515 billion in 2020. This means an annual increase of around 20%. Chemistry then will be increasingly biobased. And German companies are livening up the market not only by investing in R&D but also by stimulating Mergers & Acquisitions operations.

In November 2013, BASF bought the USA enzyme manufacturer Verenium for €48 million, thus entering the crucial enzyme market until then dominated by Danish Novozymes and American Dupont. A market that according to ReportLinker’s forecast, a French research company, should grow from $4.2 billion in 2014 to 6.2 billion in 2020.

In January 2012, Ludwigshafen’s chemical colossus invested $30 million in American Renmatrix, owner of the Plantrose technology for producing industrial sugar from lignocellulosic biomass at very competitive costs. At the end of 2013, with the same company it signed an agreement for the industrial scaling up and the future marketing of this technology. Still on the other side of the Atlantic, the German chemical company signed an agreement with Genomatica for the production of bio-based 1,4-Butanediol (BDO). The licencing agreement allows BASF to build a global-scale manufacturing plant for the production of 75,000 tonnes of bio-BDO per year. Butanediol and its derivatives are used for producing plastics, solvents, elastic fibres for packaging and the car and textile industries. BASF also signed a partnership with Dutch Corbion Purac, thus creating Succinity GmbH, a joint venture for the production of bio-based Succinic acid. In March 2014, the two companies announced the positive opening of the first plant for the production on industrial scale in Montmelò (Spain).

Still in the field of bio Succinic acid, Covestro (former Bayer Material Science) announced in October 2015 a partnership with Reverdia (also a joint venture between French Roquette and Dutch Royal DSM) for the production of a thermoplastic polyurethane material (Desmopan) from renewable sources that can be used in footwear and consumer electronics sectors. Specifically, in its production process Covestro will use bio-Succinic acid Biosuccinium by Reverdia that last year in the USA obtained the USDA Certified Biobased Product Label certifying its contents are 99% biobased. Biotechnologies are an integral part of Evonik’s growth strategy whose product portfolio already includes amino acids, biocatalysts for the production of biofuels and biochemicals, bio-based polyamides and polyesters.

Investments’ Attraction

But Germany also attracts foreign investments. French biotech company Global Bioenergies built in the chemical hub in Leuna its demonstration plant for the production of isobutene from renewable sources, receiving a €5.7 million grant for the German Ministry of Research. Tests are carried out in collaboration with Audi.

In 1997, Swiss Clariant incorporated Höchst’s chemical specialities department and in 2011 it bought for €1.4 billion Bavaria-based Süd-Chemie specialized in the development of chemical products for smelting works, special resins, battery components and precision packaging. But above all owner of the lignocellulosic biorefinery in Straubing where Clariant has carried on developing the sunliquid® process for the sustainable production of cellulosic ethanol and biochemicals from agricultural residues.

Süd-Chemie was incorporated into Clariant’s Biotechnology Group, exclusively devoted to industrial biotechnology with particular attention for the development of processes and products from renewable resources. Last October in Planegg, near Munich, they officially unveiled the Group Biotechnology Research Center (6,000 square metres of offices and laboratories completely devoted to industrial biotechnologies) that will collaborate with the Clariant Innovation Center in Frankfurt.

Each year, the Swiss company spends €30 million to expand its Bavaria-based plant’s capacity to produce bioethanol from wheat straw. “If in a few years we assess the environmental impact of the Dieselgate, we will notice that it has promoted the spreading of biofuels,” Hariolf Kottmann, Clariant’s CEO, declared to German newspaper Euro am Sonntag. He also said that he believes that within 2-4 years there will be a leap in bioethanol sales and profit.

Germany at the Centre of the World with the Global Bioeconomy Summit

To reassert its ambition to lead the European bioeconomy, at the end of November, Berlin hosted the Global Bioeconomy Summit sponsored by FAO and the European Commission: 700 delegates from all over the world (including Colombia, Malaysia, Argentina, Brazil as well as the Vatican) discussed strategies to support new economies based on biological resources. Germany knows that the bioeconomy can be developed only on a global scale, sharing vision and governance for a sustainable planetary development.

Clib2021, www.clib2021.de/en

Clariant, www.clariant.com

BioEconomy cluster, en.bioeconomy.de/

Global Bioeconomy Summit 2015, gbs2015.com/home/

Interview with Manfred Kircher, member of the Advisory Board of Clib2021

Interview with Manfred Kircher, member of the Advisory Board of Clib2021

Strategy and Strong Industrial Base: The Ingredients of the German Bioeconomy’s Success

“One consequence of the VW scandal will be that authorities do not believe companies any more. Authorities will check company claims on performance data more intensive. This might become valid for any claim of industry relevance, including GHG-reduction by bio-based fuel and feedstock. The bio-industry should avoid any unrealistic or misleading information to the public and authorities.” This is the observation of Manfred Kircher, a member of the Advisory Board of Clib2021, a German cluster for industrial biotechnologies, one of the most influential bioeconomy voices both in Germany and in Europe. In this interview with Renewable Matter, Kircher talks not only about the consequences that the so-called Dieselgate could have on the bioeconomy in Germany, but also about the strengths of a system that has adopted a strategy for some time now and what Berlin expects from the European Union to further promote the development of this meta-sector.

Mr Kircher, to date, what are the major achievements in the bioeconomy in Germany?

“German bioeconomy industries cover all relevant fields: Pharmaceuticals (Sanofi in Frankfurt is the world leader in insulin), food and feed additives (Evonik is the only company producing all industrially relevant L-amino acids), enzymes for food, feed, consumer care and industrial applications, bio-based platform-chemicals, polymers, lubricants, adhesives, bio-fuel and biogas (with more than 8,000 biogas plants Germany is leading). These products are provided by big industries like for example BASF, Evonik, Henkel and well-known SME such as BRAIN, evocatal and c-LEcta to name just a few. As the bio-economy is also established as a science topic at universities more and more promising start-ups are spinned-off.”

How important is the presence of a national strategy to develop the bioeconomy in Germany?

“The National Strategy plays a key role in harmonizing governmental measurements on federal and state level as well as private cross-institutional and sectorial programs. It also helps the ministries concerned (agriculture, economy, ecology...) to streamline public funding actions. All together the National Strategy serves as a well-accepted guide-line for all stakeholders.”

What role does the German Bioeconomy Council play?

“The Bioeconomy Council serves as the interface between public and private stakeholders. This council not only formulates the National Strategy in consultation with governmental authorities and organizations representing industry, science and civil society; it also communicates the National Strategy to the stakeholders mentioned.”

The Bioeconomy Council

In 2009, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection (BMELV) established the Bioeconomy Council as an independent advisory board to the German Federal Government. The central task of the current 17 members of the council, whose expertise covers the full spectrum of the bioeconomy, is to search for ways and means for sustainable solutions, and to present their insights in a global context. The Bioeconomy Council convenes regularly to prepare position statements and expert advice, organise events on relevant issues, and promote the future vision of the bioeconomy to broader society. The activities of the council are oriented both towards long-term objectives as well as current policy requirements.

The Bioeconomy Council completed its first working period on schedule early in 2012. The following summer, the Federal Government appointed a new committee under the same name, which began work in autumn of 2012. In the composition of members, equal consideration was given to the subject areas of the economy, science and society.

(Source: www.biooekonomierat.de)

Biorefineries are the central point of the bioeconomy. What are the biorefineries located in Germany?

“In Germany there are three types of biorefineries. 1) Individual production facilities like sugar refineries (sugar derivatives), oil mills (lubricants, bio-diesel), chemical production (bio-based polymers), fermentation plants (pharmaceuticals), biogas plants etc.. 2) Chemistry parks with bio-based production units taking advantage of the cascade use of the whole site\'s material flow. Frankfurt-Hoechst is a prominent example where the site\'s material flow ends in Europe\'s biggest industrial biogas plant. It even supplies gas to the public gas grid. 3) New biorefineries to be integrated into chemical parks. The most prominent example is the Fraunhofer pilot plant in Leuna. It targets on fully integrated production of platform chemicals from woody biomass.”

Biorefineries Roadmap

Biorefinery concepts have already been pursued for a number of years in Germany. For example, a range of activities aimed at investigating and developing diverse biorefinery paths are in various stages of realisation. Examples of these are:

- Sugar/starch biorefinery on the basis of cereal crops/sugar beet from the company Südzucker/CropEnergies in Zeitz (Saxony-Anhalt);

- Wood-based lignocellulosic biorefinery operated by a consortium coordinated by DECHEMA as part of the Fraunhofer Society’s Chemical Biotechnological Process Center at the chemical site in Leuna (Saxony-Anhalt);

- Lignocellulosic biorefinery based on straw from the Group Biotechnology of Clariant in Munich and Straubing (Bavaria);

- Grass silage-based green biorefinery from the company Biowert in Brensbach (Hesse)

- Grass-based green biorefinery from the company Biopos in Selbelang (Brandenburg);

- Straw-based synthesis gas-based biorefinery from KIT in Karlsruhe (Baden-Wuerttemberg).

(Source: www.bundesregierung.de)

From your point of view, what makes Germany an attractive country for investment in the bioeconomy?

“Investors evaluate among other factors the home market, access to global markets and production cost. Concerning the domestic market bio-based products are very well accepted and being an export-champion Germany is well established in foreign markets. Although some cost-factors like e.g. staff-costs in Germany are generally higher than in other regions the country can play out other pillars of competitiveness like excellent infrastructure, quality of personell and a reliable and supportive political and administrative framework. Looking from that angle the Bioeconomy Council turns out to act as a competitive factor as well.”

Clariant stated that the Volkswagen scandal will boost the advanced biofuels. What is your opinion? What are and will be the effects of this case on the bioeconomy in Germany but also at world level?

“One consequence of the VW scandal will be that authorities do not believe companies any more. Authorities will check company claims on performance data more intensive. This might become valid for any claim of industry relevance, including GHG-reduction by bio-based fuel and feedstock. The bio-industry should avoid any unrealistic or misleading information to the public and authorities.”

At the end of November Germany hosted the Global Bioeconomy Summit. From German point of view, what should the EU do to support better the bioeconomy and be competitive at world level?

“Firstly, products of the bioeconomy must become competitive by themselves. However, right from the start new bio-based processes and products cannot compete with (fossil-based) alternatives whose cost have been cut down over decades. Bio-based products must get the chance to enter the ‘learning curve’ of process optimization. Funding pilot- and demonstration plants through the current HORIZON2020 program is therefore the right way but the hurdle for private engagement should be lowered.

“Secondly, beside (limited) biomass new bio-processes recycling carbon from gaseous sources are currently providing another option to replace fossil carbon. Although these technologies do not discriminate between bio- and fossil carbon such carbon-recycling should be accepted as sustainable in the regulations and norms concerned.

“Thirdly, although chemicals produce in average by factor 7 more value than energy and in addition generate more jobs EU policies prioritize bio-fuel and -energy. It would be desirable to support both sectors in a more balanced way.”