In 1924 the expression “planned obsolescence” did not exist, but the phenomenon was already there. Indeed, during the same year, a few light bulb manufacturers signed a non-aggression pact: no competition amongst them and products on sale with the same reduced life expectancy. Decades after the so called “Phoebus cartel,” there was a proliferation of high-mortality products. From printers impossible to repair to the early IPod Apple, with a fast-degrading and very expensive battery to replace, so much so that it was cheaper for users to buy a new MP3 reader. If these are the most glaring cases, premature aging affect all types of devices and most manufacturers. According to data mentioned in a report on this subject carried out by UN Environment in late 2017, between 2000 and 2005 in the Netherlands, a laptop’s life expectancy dropped by 5% and that of small electronic devices by a staggering 20%. In Germany, most appliances are replaced in less than five years from purchase.

“Before, the design of a product was studied so as to optimize the production phase with that of performance during its use, with various repercussions for economies of scale, quality and durability. A number of products that up until a few years back were mere assembling of plastic and metal have now become a concentration of hardware and software encapsulated in a captivating bodywork and, when systematized, grab the potential customer’s needs and attention,” explain Damon Berry and Matteo Zallio, researchers of the Dublin Institute of Technology. If this evolution is the result of a new way of designing objects in response to customers “with an increasing power in making their needs felt,” the effects on the environment are not always positive. When the electronic components increase beyond measure, so does the probability of faults, and wherever there is software, if the manufacturer stops updating, the product ages instantly, thus becoming waste. In many instances, the very designers are asked to elaborate products with a definite life expectancy, both for corporate commercial strategy and because over the last decades lifestyles have had a tendency to frequent consumption of electronics, as testified by Dutch and German data.

If designers and consumers are part of the problem, they can also be active promoters of the solution. On the basis of a scenario already appearing on the horizon: “It is important to concentrate on designing flexible, modular, adaptable devices, simple to mend and update, moving from a design of a product to one of services,” explain the two researchers, according to whom in this evolutionary process of the market, a key role will be played by consumers: “Today, it is the users who hold the power, they have the opportunity to express their concepts and needs in a much more effective way compared to last century. Design will evolve hand in hand with people because design is still made by human beings and is a consequence of the demand from the market.”

So, in order to solve the problem of planned obsolescence, one of the smartest things to do is to start from people. This is also the approach adopted by the best initiatives at global level to stop premature death of electronic devices. As a result, by repairing a toaster, irons and smartphones, relations between people and objects are also altered and a consumption model more compatible with the Earth’s limited resources is also promoted.

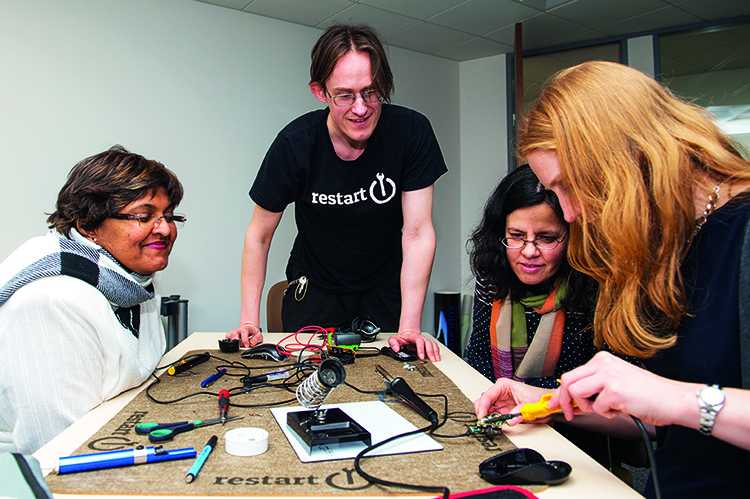

So far, one of the most successful experiences is Restart Project, an association created in London in 2012 by Janet Gunter and Ugo Vallauri. She is an anthropologist and activist with experiences from Brazil to Timor East and he is a researcher and an expert in international cooperation. Together they started out with an idea to do something against the proliferation of electronic waste that in many instances is disposed of in the Global South, amongst thousands of environmental criticalities. “We were extremely frustrated at the large amount of electronic devices being thrown away in Europe and the United States. So we started to organize restart parties in London, events where people bring their own broken devices and repair them with the help of volunteers,” tells Vallauri. The initiative was successful and became popular the world over, with affiliated groups organizing parties in the US, Canada, Israel, Tunisia, Spain, Italy and Argentina. The first 200 parties organized involved almost 8,000 people, with over 6,200 devices, of which only about a thousand proved impossible to repair. All the remaining ones are now back up and running or soon they will work again, thus avoiding the production of 8,500 kilos more waste and an amount of emissions equal to that necessary to produce 26 cars: “We don’t want to take the place of the repairing economy, but we would like to offer training and help people to share and exchange knowledge.”

Some research carried out by Restart Project in collaboration with the university of Nottingham Trent showed that 48% of Restart’s partygoers has little or no faith at all in home repairs and 45% cannot even recommend a repairer. Here the planned obsolescence phenomenon appears in all its complexity: “It’s not merely a question of companies planning products to last a certain length of time, but many devices are so difficult to disassemble and repair that many manufacturers do not divulge repairing information to users and spare parts are not always easily accessible to everyone.” All these fronts need tackling, restoring the will in each individual to try and get one’s hands dirty before opting for the easier solution of buying a new device.

Last autumn, Restart Project launched the first edition of the International Repair Day and organized the first FixFest. Also, the Open Repair Alliance was born, a group of organizations aiming at building an international standard to exchange information on repairs at global level. It will help repair objects and plan more durable devices, easier to repair.

iFixit is also part of the alliance, a project born in 2003 in California, also from some frustration: Luke Soules and Kyle Wiens studied Engineering at the polytechnic university and wanted to repair an old iBook, but nowhere could they find the instructions on how to do it. “They fiddled, tinkered with it, broke some keys and lost a few screws but in the end they managed to repair it. They tried to repair more laptops but they would not find the parts. So they bought an old computer on eBay and obtained the components from it,” tells today Kay-Kay Clapp from Headquarter in San Luis Obispo. That’s how the idea of iFixit was born, a platform for both e-commerce where spare parts are sold and a community where people from all over the world exchange repair manuals for free and reply each other’s questions. “Today iFixit boasts over 35,000 free online repair manuals accessible to anyone. Last year it helped over 100 million people repair their things.” The project motto is: “If you can’t open it, you don’t own it:” iFixit allocates a score from 1 to 10 to each device according to the level of reparability and ease of repair of the components and the accessibility of the repair information. Sometimes, adds Kay-Kay, “technological companies complain for the score we give them, but some now work with us during the design processes to have advice on how to plan easier to repair products.” The change has already begun.

Restart Project, therestartproject.org

Open Repair Alliance, openrepair.org

iFixit, www.ifixit.com