Better than Germany. Beyond San Francisco. This project is attracting a host of administrators and experts wishing to study and analyse it. It is Italy’s pride and joy. The subject of such attention is Milan’s programme for organic waste management. Launched in 2012, it is now the world’s most efficient and sustainable organic waste collection system, involving families and private businesses (restaurants, canteens, etc.). Once a back-marker among main European cities, Milan has jumped ahead in less than two years. If in 2012 less than 30 kg of wet waste per capita per year were collected, in 2013, it soared to 56 kg and in 2014, it is expected to exceed 95 kg per person per year. An impressive amount, over 120,000 tons of organic waste per year. More than any other city in the world with a population of over one million.

|

|

The communication at the heart of the project: detailed information in the kit for the collection plan, simple and effective explanations to encourage citizens. |

The urgency of tackling the organic waste issue is deftly summarized by sustainable economy guru Lester Brown, author of Plan B 4.0 and interviewed by the author. “Soil nutrients geography is changing. The soil is being depleted of substances such as potassium, phosphate and nitrates, which absorbed by fruits and vegetables, flow and concentrate in cities where they eventually end up in the sewage system, altering the balance of rivers and sea waters. This cycle must be broken.”

According to Mr. Walter Ganapini, former Milan councillor in charge of the environment, “organic waste composting could be a strategy for improving Italy’s soil”. Italy, even in the fertile Po Valley, has a low organic substance level in its soil, only 3%. In France, just to give you an idea, it is 6%. So, non-artificial organic material redistribution is essential.

“We must also take into consideration the ensuing climate change issue” explains Mr. Ganapini. “If organic waste is not adequately managed it can contribute significantly to the emissions of climate-changing gases.

According to Prof. Davide Figliuolo, a researcher at Università Statale in Milan, composting of Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste through separate collection (OFMSW in technical terms) is able to capture directly 17.6 kg of CO2 per ton. If avoided emissions are taken into account, deriving from the non use of chemical fertilizers and peat as a structuring material, the total of non-emitted CO2 amounts to 65.3 kg per ton of wet waste managed.

Implementing OFMSW management projects such as that of Milan could easily become a conservative strategy for many other urban areas. Besides compost, from the organic fraction it is possible to generate energy from anaerobic digestion and biogas production. Organic waste, which amounts to a third of Northern Italy cities’ waste, could become an urban asset in its own right. “As long as it is carefully managed and it can produce the hoped-for results.”

In Milan, this process has turned into reality. According to an ISPO survey, 90% of the citizens are backing the project, while a small minority thinks it is useless. This means that OFMSW has become part of the city’s collective imagination. The Municipality involved agencies such as AMSA (Milan’s utility company for environmental services) and Novamont, a company that opened Italy’s first biorefinery, have worked with great professionalism. Let us see how.

Interview with Pierfrancesco Maran

Pierfrancesco Maran is councillor in charge of environmental and transport affairs for the Municipality of Milan and is one of the administrators engaged in the launch of the OFMSW collection project, talked to Renewable Matter to explain the Public Administration’s role in this project.

The Milan model

How was the idea of reintroducing organic waste collection in Milan conceived? Was it initially met with opposition?

Strengthening separate collection and reintroducing organic waste collection was one of the most important points of Giuliano Pisapia’s electoral programme. At city level, we cannot talk about environmental policies without wet waste collection that entails a drastic reduction of waste collection. There was no opposition. Milan had already tried wet waste collection in the past and then it was suspended, so its people were already “used” to the idea of separate wet waste collection.

Wet waste collection is expensive. What are the economic, environmental and social benefits for city dwellers?

Considering that separate collection of recyclable waste is provided for by Italian and European regulations, the benefits of wet waste collection for city dwellers are above all of environmental nature: organic waste does not end up in an incinerator (in Milan, nearly no waste ends up in a landfill) but is processed so as to produce compost to be used in agriculture and energy from the production of biogas.

What is the role of the municipality in the success of this project, considered one of the best the EU? What is the advantages of having private partners such as Novamont?

Pisapia’s town council will and vision were determining factors in strengthening separate collection and the operational and financial support of private partners was crucial to carry out this project. This collaboration resulted in a very important cultural revolution.

How important was it to find a way to explain the collection to both Italians and immigrants?

Communication in nine foreign languages is vital in a multi-ethnic city such as Milan. Here many foreigners work as cleaners and keepers. The PULIamo app has proved to be a useful tool for reaching the young and students coming from other cities where separate collection is not widespread or other people not used to this activity.

Are you promoting the Milan Model in other Italian municipalities?

Across Italy there are small municipalities that are doing very well in separate waste collection but the Milan Model is very interesting for other major cities. We are particularly proud because foreign cities delegations (Paris, London, Shanghai, Berlin, Saint Petersburg, San Francisco, Barcelona and Oporto) have often expressed an interest in knowing our door-to-door separate waste collection, especially for organic waste.

Will there be other urban composting projects such the experimental one carried out at Cascina Cuccagna last year? Are there projects for this purpose in urban vegetable gardens?

Yes, absolutely. There are several projects either underway or about to start, especially in schools. Milan is adapting very well to this new lifestyle. Not only at home, but also in offices, in public spaces, in restaurants and bars separate collection is becoming more and more popular by the day.

A Story of Waste

Milan had already launched an experimental project on OFMSW collection in the mid-1990s. Nevertheless, in 1999 it was suspended because the quality of collected waste was unsatisfactory. A commercial waste incentive (canteens, restaurants etc.) was preferred.

“The project took off in the Bonola area” explains Mr. Ganapini, who at that time was responsible for managing the 1995 waste emergency in Milan. “But the council led by Albertini made a huge mistake deciding to close down prematurely the wet waste collection. This created the perfect conditions that led Milan to overshoot the targets of the EU Waste Directive. And probably the biggest mistake was to close down the model composting plant in Muggiano in 2005 commissioned by the Letizia Moratti’s administration”, mayor of Milan and famous for her wild promotion of incinerators, including the much-disputed Acerra plant in Campania.

In 2011, with the new Milan Mayor, Mr. Giuliano Pisapia, his campaign very much focused on environmental issues (waste, cycle paths, urban parks, pollution fighting), organic waste collection was given new impetus, thanks also to the commitment of Mr. Pierfrancesco Maran, councillor in charge of environmental and transport affairs.

“There was an immediate concurrence of interests between AMSA and the Municipality of Milan which, in early 2102, led to a four-step project, dividing the city in as many areas to carry out experiments in order to evaluate the feasibility study of such process”, explains Ms. Paola Petrone president of AMSA, interviewed by Renewable Matter. The process took off rapidly without any problems in one area after the other. Wet waste collection in the North-West area, the last to be launched, started on 30th June 2014, thus offering 100% coverage of the Municipality of Milan’s area. A result than many thought impossible.

The Mechanics of a Project

The rapid implementation of OFMSW collection is based on a careful mix of managing skills and a global strategic vision. According to Mr. Enzo Favoino, teacher at Parco di Monza Agricultural School, and one of the experts who took care of the implementation of the project, “in this kind of projects logistics is crucial. To this end, a preliminary study was carried out to optimize collection, identifying what strategies to adopt and how to lay out equipment (buckets and bins) with a detailed census of the area carried out by AMSA to map existing facilities and possible issues”.

AMSA seized the opportunity of implementing its own mapping of collection points and went from house to house to decide where it could locate its bins, assessing blocks of flats’ space and suggesting solutions where space was limited. The company registered and classified in its database as many as 55,000 collection centres.

“In some cases we had to ask neighbours to provide space for ad hoc collection areas or we had to provide communal collection boxes.”

According to Mr. Favoino, besides a study of the collection context, in blocks of flats it was crucial to find a door-to-door collection strategy able to maximize people’s comfort and to meet caretakers’ and maintenance companies’ requirements.

Micro-composting and Short Supply Chain

In Milan, there are several wet-waste micro-recycling initiatives. The most interesting is that carried out in 2013 for six months by Cascina Cuccagna. The Cascina (farmstead) is already located in an area served by AMSA door-to-door wet waste collection. Nevertheless, the consortium, led by Mr. Andrea Di Stefano, came up with the idea of trying a zero-km compost production model to show people “the fruits” of wet waste collection. They created a composter to produce a fertilizer to be used in the Cascina’s vegetable garden, by residents and in local urban vegetables gardens, gardens and balconies.

Thus the Erica Cooperative set up a prototype of “community composter” that in six months “digested” a total of 2.6 tons of organic waste (mainly donated by the Esterni Group’s restaurant called “Un posto a Milano”) transforming them in its fermentation and sterilization chambers in sustainable compost. Residents were able to see how organic waste fed into the composter was ground and mixed with a dry structuring agent (pellets) and then stored in a chamber where fermentation took place, accelerated by the presence of material already fermenting. Forty days of “transformation” and then the product is ready to use.

In six months, Cascina Cuccagna transformed 2.6 tons of wet waste, producing 40 kg of compost for every 100 kg of wet waste in 3-4 weeks. A good example of composter that citizens’ associations, urban vegetable gardens groups and other “urban agricultural” contexts can implement cheaply. A real short waste supply chain.

“Although the whole project had been carefully planned, it can be argued that communication was key to its success.” Ms. Paola Petrone and Mr. Pierfrancesco Maran are convinced of this as well as all interviewees. Without a detailed communication campaign, such surprising results would not have been achieved. An actual campaign to conquer “citizens’ hearts and minds”: convincing about one and a half million people, with different social and cultural backgrounds, is no mean feat.

The adopted strategy was one of great operations: exploiting every available channel with simplicity and pragmatism. “The first action was to send two letters to every family living in Milan presenting the project and illustrating in a simple way how to collect organic waste”, Mr. Petrone explains. “Then we opened a dedicated telephone service to solve any doubt or puzzlement. Data show that in the first few months AMSA and Comune (municipality) hotline received and average of one hundred calls per week. The joint venture acted directly meeting citizens, caretakers and condominium managers to illustrate the project in details. We organized meetings with all district committees; we set up information stalls in neighbourhood fetes and demonstration composting projects.” Even in the most difficult and degraded districts, trying to explain the project to foreign families that have often very little information on correct waste management.

This is why all information literature was made available in nine languages. On amsa.it website instructions are available in Spanish, French, Sinhalese, Arabic, Ukrainian, Chinese and Romanian. A careful choice made taking into consideration Milan’s ethnic make-up. However, paper communication played the most important role: leaflets were hung up in all waste collection areas and provided to all home units during the painstaking distribution (defined as “Habsburg-like” by AMSA) of OFMSW starter kits. In the 2.0 era, there was also an app to illustrate how to make efficient use of the brown bin.

Private sector support was also crucial. Novamont, a bioplastics colossus, donated one million Mater-Bi bags, a type of plastic patented by the company. “This was a very important collaboration for AMSA” Ms. Paola Petrone explains, “that was crucial for the carrying out this project”. Compostable bioplastics bags, which are waterproof, hygienic and breathable, are essential when using anaerobic digestion and composting plants. Bag compostability is a fundamental characteristic in order to guarantee the quality of collected material. Although today, thanks to the law banning plastic bags, many people use bioplastic bags, supplying 25 Mater-Bi bags helped educating people. In many towns, the main problem facing OFMSW collection is non-compostable plastic bags. Thanks to this supply, citizens start to get used to bioplastics.

According to Mr. Christian Garaffa, Novamont managing director, the majority of small shops still uses bioplastics bags correctly. A thorough application of national regulations on carrier bags would improve the service (for further information on carrier bags, please read Mr. Francesco Ferrante’s article in this issue of Renewable Matter.)

|

|

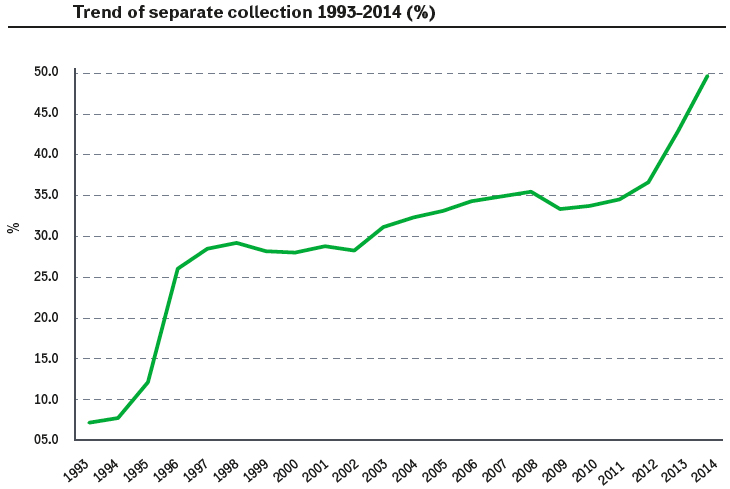

Milan on top of the world: the introduction of staff has accelerated the share of separate collection for years struggled to increase. |

Where Waste Ends up

Approaching the tipping area that every day receives articulated vehicles with 30-ton loads, a careful visitor is surprised that the private plant in Montello (Bergamo) – a 35-hectar plant with a 12-hectar roofed area – does not give out the strong smell characterizing so many waste collecting plants. Here, through an isolated system, Milan’s organic waste, as well as other areas’, is transformed into biogas and then into compost.

The method adopted at this plant consists of a pre-treatment of waste followed by anaerobic digestion (in order to produce biogas used to generate electricity and thermal energy) and by a final aerobic composting stage of sludge deriving from dehydrated digested material in order to produce quality organic fertilizer.

Thanks to its digesters, the plant’s emission reduction amounts to 75,000 tons of CO2 per year.

All the thermal energy produced by the Montello plant is used to run its services and facilities (i.e.: to warm up its digesters); electricity is also used to run the plant while the surplus is fed back to the grid. The Montello Plant has a 10-MW generation capacity. Compost is given to farms free of charge.

Economy of Waste

It cannot be denied that collecting and reusing OFMSW through separate collection entails extra costs. Nevertheless, according to a 2010 official study carried out by Regione Lombardia, costs tend to fall with higher separate collection rates, this is due to savings in waste disposal and revenue from recyclable materials. However, according to AMSA and local authority interviewees, in reality it is seen as an extra cost. “But if we take into consideration positive impacts on the environment and on public health, we can identify some savings” Ms. Paola Petrone argues.

|

|

Bad habits: despite the project’s success there was a decrease of attention of the citizen in correct waste separation. |

These are not easy estimates. But when taking into account emissions of greenhouse gases and particulate, nutrients given back to the soil thanks to the distribution of compost to local famers and biogas production as a source of renewable energy representing an alternative to fossil fuels, it is easy to understand its advantages.

According to Mr. Favoino, changes in costs of alternative methods to organic waste collection must also be taken into account. “Thirty years ago, landfill disposal was cheap, but today landfill costs have risen due to compulsory pre-treatments to avoid biogas and leachate production. In the medium term, incineration costs also show an upward trend due to emission regulations requiring more and more sophisticated treatment technologies.” In reality, the more we recycle, the more we save. The situation though varies from country to country according to Michael Kern, a waste management expert at Witzenhausen-Institut. “In countries where incineration costs are low, incinerating competes with organic waste collection and it is more difficult to promote OFMSW management.”

“Italy though” Mr. Favonio adds, “has introduced intensive and optimizing models of separate collection that offer the chance of containing collection costs compared with traditional Central European models. As shown by official sector studies, this is a strategy that enables to increase separate waste collection by 20 to 70% without entailing a real cost increase. Of course, this is true in the medium and long term, when operative models can be optimized; in the short term pre-existing conditions can reasonably become conditioning elements.”

In Milan, for citizens and local government officials alike, this is undoubtedly a positive experience and it does not really matter if it is slightly more expensive. It is something to be proud of and it helps the environment. The project has risen a great deal of interest both at national and international level. “We have received delegations from Paris, Stockholm, Shanghai and Berlin. We have had many exchanges and we are often invited to illustrate the project” Mr. Petrone says.

Rome seems to be one of the few cities that has not yet contacted Milan.

Info