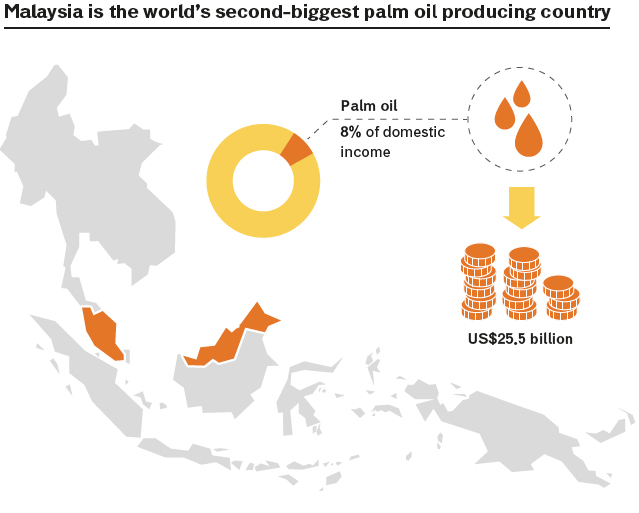

Nevertheless, are agricultural waste and refuse able to feed the whole bioeconomy? The global situation we are faced with at the moment is very complicated: on the one hand, the demand for biomass is on the rise not just for bioenergies but for the so-called biomaterials and biochemicals, on the other, there are countries offering great amounts of biomass to the bioeconomy’s world market such as Malaysia, Canada, Brazil, as well as countries of Northern Europe and Russia boasting huge forest resources. It’s no coincidence that Biochemtex, a company of the MossiGhisolfi Group, after the inauguration of the biorefinery for the production of second generation bioethanol in Crescentino (Vercelli, Italy), is planning to repeat the Italian plant in Brazil, China and Malaysia. The government in Kuala Lumpur has included biomass at the very core of its economic development plan for the next few years. In 2011, a National Biomass Strategy 2020 was presented, with a focus on palm oil, already contributing to 8% of GDP: almost 25.5 billion dollars (Malaysia is the world’s second largest producer and exporter of palm oil). The objective is to raise the bioeconomy’s contribution to GDP from the current 2-3% to 8-10% by 2020.

Michael Carus, CEO of nova-Institut – a private research centre based in Hürth, near Cologne, Germany – has analysed this subject in quite some depth. Nova-Institut is regarded as a very prestigious institution and represents a benchmark in Europe and the United States, often quoting its research data in their support scheme to the bioeconomy “Biopreferred”.

But what is the correct definition of biomass? Experts define it as the biodegradable fraction of products, waste and biological residue from agriculture (including plant and animal substances), from silviculture and deriving industries, including fishing and aquaculture as well as the biodegradable share of industrial and urban waste.

According to Carus, nowadays the real problem is not so much its scarce availability but rather its “improper allocation”. Mostly in Europe. Overall, the bioenergy and biofuels should represent approximately 60% of the whole of renewable energies envisaged by the European Directive (RED, Renewable Energy Directive) and about 90% of the transport share by 2020. If those percentages were reduced to 40, 50 and 80 respectively, a significant amount of pressure would be lifted from biomass.

Michael Carus, managing director of the nova-Institut, at EFIB 2012, Dusseldorf

Such regulation would be more useful compared to limiting the share of first generation fuels; indeed they can prove more efficient with regard to the employment of local resources as opposed to those of second generation. The missing percentage – as the German researcher suggests – could be obtained by a higher share of solar and wind power as well as other renewables. As to other biofuel percentages in the transport sector, it should be borne in mind that alternative means such as electric and carbon-dioxide powered cars are not yet sufficiently available on the market.

They must nevertheless be adequately promoted in order to limit the use of biomass.

Carus is one of the very few in Europe who strongly believes that the contrast between first and second generation biofuels is useless. In one of his studies – “Food or non-food: which agricultural feedstocks are best for industrial uses?” – the German physicist explicitly writes that “all types of biomass should be accepted for industrial use”.

The choice should depend on how sustainable and efficient can the process to obtain biomass be. Political actions should not only distinguish between food and non-food crops, but they should rather employ criteria such as the availability of land, resources and land efficiency, optimization of by-products and emergency food reserves. There is an abundance of studies demonstrating how many food crops are more efficient in the use of the local resources compared to non-food crops. This also means that less land for the production of a certain amount of fermentable sugar – crucial for biotechnological processes – is needed compared to the amount required to produce the same amount of sugar with the allegedly “non problematic” lignocellulosic second generation non-food crops.

Carus explicitly criticizes the EU’s bioenergy and biofuels policy, as provided for by the ambitious objectives set by RED, because it entails systemic allocation of biomass for energy production to the detriment of materials. RED (in the future it will be linked to FQD – Fuel Quality Directive [Directive 98/70/EC] – in the transport sector) has triggered the development of national action plans and support systems for bioenergy and biofuels. And in turn this has caused both biomass prices and agricultural land lease to rise, making it more difficult for other sectors to get hold of biomass.

There is improper allocation of biomass since this is blocking the development of “high value” materials such as chemical products and plastics. Therefore the development linked to RED will have a deep impact on the availability of biomass for the materials industry. An unfavourable regulatory framework combined with high prices and unsteady supply of biomass discourage investments in the chemical sector and in biobased plastics – even if they could generate a higher value and better resource efficiency.

Taking all this into consideration, Carus asks for a reform of RED into REDM, where “M” stands for materials. And he demands – followed more and more by the main actors of the European bioeconomy – a level playing field, that is equal opportunities for all sectors. Even OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) – as the nova-Institut highlighted in its latest report devoted to this issue and published last October – has emphasised how “generally biofuels enjoy much greater public support than biobased plastic and chemical products. This could jeopardize the development of the bioeconomy, making it unsteady and it could hamper the use of biomass for bioplastics and biobased chemical products. It could also limit the development and the operation of integrated biorefineries”.

A new political framework for a more efficient and sustainable use of biomass is desperately needed. More specifically, it means equal opportunities for energy and materials industries. Until 5 or 6 years ago this was a worldwide problem, but nowadays it is manly a European issue. In America and Asia, the regulatory framework is much more favourable to biobased chemical products and plastics than in Europe.

Consequently, the USA, Canada, Brazil, Thailand, Malaysia and China are attracting most of the new investments.

For Europe, still grappling with the worst postwar economic crisis, this is not encouraging.

As far as biofuels are concerned, the EU is still stalemating

First or second generation biofuels? After many years of animated discussion on this topic, last June EU energy ministers agreed on reducing the use of first generation biofuels for transport to 7% by 2020 and encouraging the transition towards second and third generation biofuels (which should represent at least 0.5% of the 10% goal).

But the issue is far from solved: now an agreement must be found between the Parliament and the Council to reach a common position on the legislation. In September 2013, the EU Parliament set the upper limit of first generation biofuels from food crops to 6% in contrast with 5% previously suggested by the EU Commission.

BASF: The Chemical Company becomes Biochemical

BASF: The Chemical Company becomes Biochemical

Interview with Michael Nettersheim, investment manager at Basf Venture Capital

The Chemical Company is the simple and catchy slogan of BASF, a German company, world leader in the chemical sector. We are talking about a colossus that in 2013 had a turnover of €74 billion and employs 112.000 people worldwide. There is no chemical department where the Ludwigshafen Group is not present: chemical products, plastic materials, high performance products, agrochemicals, oil and gas.

But for how long will all this be petroleum based? Oil prices and above all limited fossil resources are pushing even the chemical company par excellence towards the use of renewable raw materials such as sugar and plant waste. Because even if in the coming decades the chemical industry will remain mainly petroleum based, due partly to the cost and the limited availability of biomass, there is an enormous potential for increasing the use of bio raw materials. According to OECD by 2030, 30% of all chemical products will be biobased. Is The Chemical Company destined to become The Bio-Chemical Company? Renewable Matter will discuss this topic with Michael Nettersheim, BASF Venture Capital investment manager, a pillar of its innovation strategy who has been given the task to find the world’s best start-ups.

Mr Nettersheim, why did BASF decide to set up its own Venture Capital?

In 2001 BASF decided to implement BASF Venture Capital. We invest in start-ups developing innovative technologies, based on new chemical materials as the relevant factor of success. Our goal is to facilitate access to for BASF new areas of technology. Consequently, our activities are very much focused on executing this strategic aspect. We do this by facilitating cooperation between BASF group and external partners – and of course by investing in promising start-ups. We invest preferentially in start-ups which have innovations for existing BASF Group activities, work in project areas of BASF New Business GmbH, or that are active within BASF Group growth and technology-fields.

Is the bioeconomy a driver in the investment decisions of BASF Venture Capital?

Industrial biotechnology, raw material change and agricultural products are technology fields of high relevance to BASF. Therefore, we closely look into these sectors. Over the years we have invested in several start-up companies that are active in these technology fields and develop innovative products and solutions. In addition, BASF cooperates with several external partners in order to develop new products and technologies.

Could you mention the start-ups you have invested in?

BASF has made two investments in the bio-based chemicals area: Allylix and Renmatix. Both of these are US-based, Allylix (last November the company was acquired by Evolva Holding, a global leader in sustainable, fermentation-based approaches to ingredients for health, wellness and nutrition, editor’s note) has a platform technology for the production of complex molecules for the flavour and fragrance industry through a fermentation approach. Renmatix is developing a technology for the beginning of the chemical industry value chain, namely cost efficient and sustainably produced industrial sugars, which can be used as feedstocks for a vast array of fermentation processes. This technology, combined with upcoming fermentation technologies for the production of basic chemicals, monomers, complex molecules etc. will give cheap and green solutions for the chemical industry, both “drop-in” solutions and new bio-based alternatives. Indeed, this technology could be seen as providing the feedstock for the whole (bio)chemical industry. Crucially, the Renmatix technology is based on using non-food/feed competitive raw materials, e.g. wood.

It seems that your investments are focused on the US market. How do you consider the perspectives of growth of bioeconomy in Europe?

In principle, the growth perspectives are positive. Leading companies such BASF and some of our competitors have significant operations in Europe. Academic players are also competitive with some room for improvement. Key challenges for many of the start-up companies are attracting experienced and skilled management as well as accessing venture capital especially in the early phases of development. Compared to the US this is the major bottleneck for emerging European high-tech companies.

According to the OECD, in 2030 30% of all chemicals will be bio-based. How heavy is this provision in the strategic investment decisions of a chemical giant as BASF?

In a very dynamic market environment we do see renewables also in the long term as one of several options in helping to ensure a sustained supply of products and are exploring new applications in many areas. Our customers are more and more requesting products from renewable resources. Therefore, this field is from a technology and investment point relevant for the Corporate Venture Capital activities of BASF.

BASF steam cracker at Ludwigshafen, Germany

© BASF