True, not all objects around stemmed from a designing mind: a great deal of anonymous design (just think of the “Hidden Forms” exhibition held in 2014 at Triennale di Milano) has made quite an entrance into our lives, but from “the spoon to the city” designers were able to produce many things.

This is precisely what – more than any industrial revolution – transformed human life: big and small innovations available in the USA during the first half of the 20th century generated an astounding increase in wellbeing and quality of life.

The criticism raised from the Seventies onwards – suffice it to think of giants such as Victor Papanek and Enzo Mari – has been relegated to an intellectual area, within a debate for a limited number of people. Then, during the 80s, worn out by “everything” that was designed, designers took it upon themselves to redesign everything.

At the time, the supply market did not ask itself too many questions, it only asked for shapes: this was the design’s task. The diktat was to interpret shapes, which had to be seductive and impressive: a sort of vanity fair untouched by the early debates in Italy and Europe on the limits of development. Designers went undisturbed inventing sensual and silky surfaces, mystifying matter, making cool any type of veneer of pattern. So, our matter universe has become more and more mixed, varied and confused. The economy was taking its course: it generated deficit and public debt, but it did work and no questions were asked.

The Onset of Doubt

The Onset of Doubt

The early debates on separate waste collection of materials – dating back to nearly 20 years ago – were also an attempt, rarely fully understood, to simplify an obese, omnivore and therefore complex reality.

Meanwhile, directives on waste were introduced that changed the face of public policies and also private responsibilities in the field of waste management (that at the time were not yet defined as resources). In particular, the 2001 Green Book on integrated product policies (IPP) called upon the importance of the life cycle and therefore the value of ecodesign.

Actually, already in the late Nineties, Europe urged people to reflect on the need to integrate environmental policies to improve products and services within their respective life cycles. The key issue was how to obtain, in the most efficient way, more ecological products: back then, there was a lot of talk about the imminent revolution produced by recycled materials that were supposed to re-enter our lives as re-matter and about how consumers could use them.

In order to hope for a brighter future – with less consequences to manage – that was the game to play. Sadly, designers sensitive to those issues were few and far between because there were few entrepreneurs in that environment willing to hire them; design was still an exotic concept, so in those years green products were ugly, very few, poor and often too leftist.

They had no appeal and were ideological. Nor were they democratic, since they were too expensive and rarely affordable by the masses.

However, in the 90s, designers were entrusted with a new task: designing new ecological processes and services, not just mere products. With the end of hedonism of the Reagan years, designers were able to reinvent themselves – in the role and function – in a sustainable way. Ezio Manzini became the famous prophet that ushered in the passage from products to services. These were the years when the need to express creativity not just in the designing not only of goods started to take shape. Such creativity was also applied to interactions, reciprocity, new paradigms, itineraries and sustainable functions.

Today the ecodesign principles defined for products linked to energy consumption of energy efficiency (Directive 2009/125/CE) look like literature. However, despite their predictability and unable to make news, their application has introduced large benefits for the environment and the wallet. Moreover, best practices, that up to 10-15 years ago were only a few dozens, are more and more ingrained in businesses: a proliferation of training programmes are proof of that, as well as the debates at the European Commission, at national and even at local level.

The green economy, now the circular economy, employs an increasingly higher number of people: according to the EU Commission estimates, European jobs in this sector have now reached 400,000.

Circular means the ability to produce and consume goods so as to generate a kind of wealth that does not disperse, that does not generate useless output and that regenerates and uses all (or almost) that it encounters in its way.

An autotrophic economy which takes inspiration for its roots and creativity from the recent crisis.

But, almost simultaneously, the Third Industrial Revolution makes its entrance, i.e. the digital society. The latter is bound to disintermediate with more and more ease production codes and dematerializes knowledge only to recompose it according to other paradigms, designing a challenging future, unthinkable up until the day before yesterday.

So, on the one hand, we have the crisis, making matter recycling advantageous, by also regenerating the idea of the gift economy and services. On the other, digital innovation, characterized by its bits instead of matter.

In this way, the designers’ role becomes increasingly important because, together and thanks to new entrepreneurs, must shape change... and not just mere products!

Some designers manage it by becoming self-producers, other by introducing eco-innovations (sometimes even digital ones) in traditional businesses, often designing processes of access to goods rather than ownership. And others still by intervening at social level redesigning relations and interactions against the backdrop of urban contexts where civil society becomes a protagonist, in search of more contemporary relationships and developments.

Circular Actions

What are the distinctive features of the circular economy that underpin designers’ actions?

When it comes to self-production, the ability to use local resources that don’t travel many miles (and therefore they do not pollute much) and become and expression of territoriality, one of the key elements of the circular economy. If such resources are production waste, i.e. of processes that may be used in products and self-products, one of the most important principles of the circular economy is applied: the industrial symbiosis.

Reuse can be done every time a material can be re-processed without compromising its performance and actually improving its value (upcycling). It is also a cultural breakthrough because artisans carry out the process, in small quantities, where imperfections are more and more acceptable, giving up unpleasant plastic surgery.

The circular economy shares also resources, technologies and knowledge because everything that is shared often optimizes production processes and generates efficiency; designers have been pioneers in sharing equipment, creativity and resources.

Sharing 3D printers (through fablabs, 2.0 services etc.) makes us think that another common denominator between product/designer and the circular economy is 3D printing, simplifying processes (planning, development and time to market are shortened), using measured matter (no waste), it can operate with renewable energy, it can employ recyclable matter, generate combinable but separable components from others... and above all contribute to regular reparation.

So, 3D printing that many makers love, activates maintenance/reparation of goods by generating a supporting spare parts service wherever the standard one were not available or inaccessible.

It could be one of the largest enemies of programmed obsolescence and those who believe in a future that regenerates goods rather than cannibalizing them ad infinitum may find this new system to their taste. But 3D printing is also circular where it manages to use local resources (avoiding risks of volatile and geopolitically fragile material supplies) and designers are very sensitive to their local territories, and are particularly able to grasp social nuances, interpreting them with an open mind, often better than an organized business.

Pearls of Ecodesign

The ecodesign principles defined in the Annex 1 of the Directive 2009/125/CE (ERP – Energy Related Products) envisaged:

- Minimization of material and energy consumption > less waste production and reduction of use of resources

- Reduction of use of dangerous goods > less polluting and harmful process output and consumption

- Smooth product and recycling and reuse > less waste production with same performance

- Use of renewable, biocompatible and local resources > effects on quantity and quality of generated waste

- Optimization of product life (therefore their life is extended) through easy updating, maintenance and little functional obsolescence > less waste production with same performance over time

- Simplification disassembling operations of products > improvement of differentiation of waste types and ensuing increase of its quality

Regenerating a Community, not Just a Product

The social role of design should not be underestimated. In this respect, Alvaro Catalàn de Ocòn is particularly enlightening. With his Pet Lamp he teaches us that local traditions, an utmost and outstanding example of self-production, can still renew themselves through a more modern and smart self-production. They should not be destined to remain old-fashioned or kitsch as sometimes it happens in our mind. Quite the opposite, archetypal shapes can be re-connoted thanks to global strategies (PET bottles discarded everywhere) combining with local ones, giving a new sense to makers (who have always known them) regenerating a community and a trade, not just a product.

This is also the power of designing: regenerating a trade, thus carrying out a social role. This factor is in line with the circular economy because it optimizes human and social resources.

Last but not least, the hub revolution must also be mentioned. Such aggregation centres of widespread creativity and new supportive identities. Here designers are employed even less to design matter, but to plan processes and relations on territories, to invent new formulas to stimulate and convey creativity and resources, to think in a disruptive way, and therefor more able to imagine our future.

When we ask a product designer to talk about ecodesign or whether he is sensitive to the theme of sustainability he/she answers: “This is so last century! Today if you have not an eco approach to a project, you are invisible!”

Accessories for the Leuvenhaven table

Project by Sebastiano Tonelli developed in Rotterdam within an Erasmus at Willem de Kooning Academie.

Sebastiano Tonelli graduated in 2015 with “25% Collection” at NABA in Milan where he completed his three-year couse in design and his two-year specialization in Product Design.

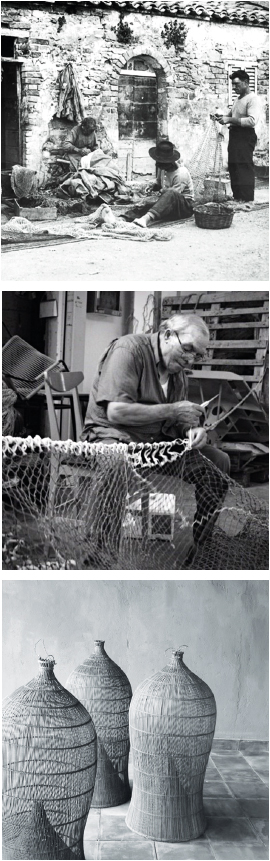

Leuvehaven was born out of a cultural dialogue with local craftmanship and its products. In Holland the lure of embroidery and fishing are still very strong. Leuvehaven is born out the iconic recovery of such tradition and the fishing nets used.