Traditional forest industry products (like pulp and paper) are a vital part of the bioeconomy. Here we take a closer look at other emerging products.

Forest resources are becoming an interesting alternative for the bioeconomy as the acceptance of food chain biomass reduces. The transition from first generation to second generation is well under way and we have already seen the first commercial investments in 2G (Second generation) biofuels: Beta Renewables came on stream in Crescentino, Italy, last year and the next wave of investments is already in the pipeline in the USA. All of these are still based on 2G agriculture biomass, but woody biomass is also becoming an option.

And the bioeconomy is not only bioenergy – although all too often we see it as the main use for biomass. Nowadays shale gas is distracting interest from bioenergy. The USA is already heavily deploying shale gas resources and the EU is gradually acknowledging it as an alternative for energy generation with European Commissioner for Energy Günther Oettinger referencing it as he presented the new EU energy and climate targets. This could create an opportunity to drive biomass for more valuable conversions too, including chemicals and materials.

|

|

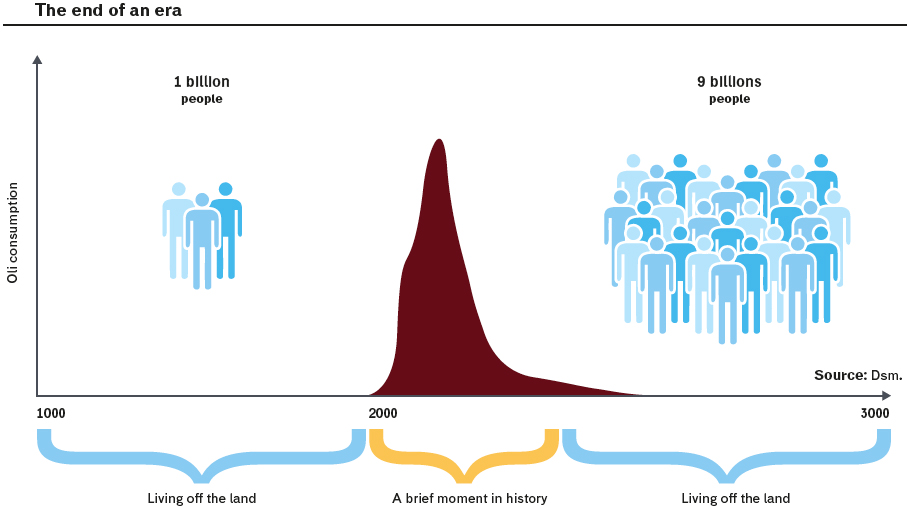

The Oil age will end long before we run out of oil. And while running out, it will become much more expensive. |

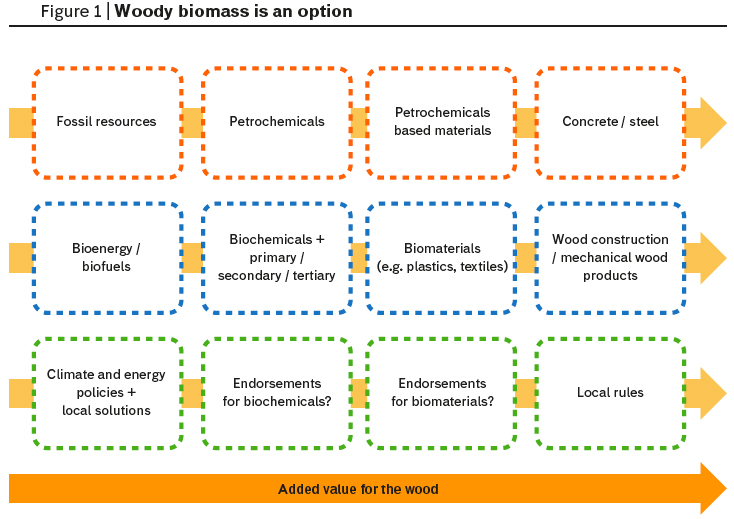

Woody biomass is an alternative source for various applications and commodities as depicted in the figure 1. At the moment the EU regulatory framework is directing biomass for energy use and forgetting opportunities in the other biosectors – such as chemicals, materials and the mechanical forest industry.

|

|

Source: NISCluster. |

The European Commission has recently issued a new proposal for energy and climate targets. The key difference compared with the current approach is that there will be fewer binding targets. Indeed it seems that the only binding target is a 40% reduction in Greenhouse Gases (GHG). The former renewable energy source target of 20 % has now been superseded by an EU-wide target of 27% with no specific obligations for member states. This could result in a slowing of investments in bioenergy unless member states take the initiative in imposing adjusting measures.

Chemicals, like materials, are currently dominated by derivatives of petrochemicals. The petrochemical industry has been well developed for decades. Petrochemical companies represent some of the largest organisations in the world and their refineries are massive. There is enormous economy of scale in terms of company and refinery size favouring the existing model and biorefinery simply does not have the scale to compete in either the bulk chemicals or niche chemicals market. It would require significant resources to create new products and new demand.

In materials, paper-based products already dominate in the printing, sanitary and partially in the packaging industries. These are all good examples of the bioeconomy.

Similar opportunity exists in industries like plastics and textiles. World plastic consumption is less than 300 Mton and today only a few percent is based on biomaterials.

The picture for textiles is a bit better – with some 5% based on biomass-based viscose. As populations grow so consumption in these sectors will increase and this presents significant opportunities for woody biomass. Woody biomass can be converted into materials in a variety of ways: through further conversions of fibre or via a chemical route. Fibre conversions are the basis for products like dissolving pulp, microcellulose and nanocellulose products. It can be done via mechanical, chemical or biological treatments. This means that conversion products will have functional properties and be able to bring added-value compared with petro-based products.

Another way to tap into biomaterials is to decompose the fibre structure. This is mainly done via sugar conversion but will mean lower yields and less competitiveness against non-renewable sources unless all components of woody biomass, including lignin, can be holistically deployed and utilized.

Sawmills, plywood and mechanical wood products are a vital part of the bioeconomy. It has been said that mechanical wood processing is the backbone of the bioeconomy, and saw mills in Europe are using almost 200 M m3 round wood for processing – accounting for almost half of the continent’s total wood consumption.

The use of concrete in construction contributes some 5% of total global GHG-emissions. Wood construction is a viable way to reduce the greenhouse effect and, with side-streams from mechanical wood processing always 40-50% of the wood intake, would provide a natural source of raw materials for novel biorefining concepts.

Nova Institute has introduced a proposal to facilitate value creation for the biomass sector called “Proposals for a Reform of the Renewable Energy Directive (Red) to a Renewable Energy and Materials Directive (Remd)” (see box). All the ideas outlined above are well in line with it. If the EU is to incentivise the bioeconomy it should not confine itself to bioenergy alone, but also consider the potential of biomaterials.

In summary, a great deal is already underway in the bioeconomy. The forest industry has deep insights into forest management and supply chains and is well positioned to seize the opportunity and play a vital role in the bioeconomy of the future.

From the misallocation of biomass to the renewable energy and materials directive (Remd). The revolutionary proposals of nova-institut

“Which agricultural feedstocks are best for industrial uses?” This is the title of the paper published on July 2013 by the German nova-Institut led by Michael Carus, who is one of the authors, together with Lara Dammer. In less than ten pages the two authors analyze one of the most controversial issues of the bioeconomy, also underlined by the decision of EU Energy Council to limit the share of food-based biofuel used in cars and trucks to 7% of the total consumption. The paper “is based on scientific evidence and aims to provide a more realistic and appropriate view of the use of food-crops in biobased industries, taking a step back from the often very emotional discussion”.

According to Carus and Dammer “all kinds of biomass should be accepted for industrial uses; the choice should be dependent on how sustainably and efficiently these biomass resources can be produced. Of course, with a growing world population, the first priority of biomass allocation is food security. The public debate mostly focuses on the obvious direct competition for food crops between different uses: food, feed, industrial materials and energy”.

However, the authors argue that “the crucial issue is land availability, since the cultivation of non-food crops on arable land would reduce the potential availability of food just as much or even more”.

Carus and Dammer suggest “a differentiated approach to finding the most suitable biomass for industrial uses”. In particular, they suggest to consider some aspects, such as the availability of arable land, the resource and land efficiency, the flexibility of crop allocation in times of crisis. According to the authors, “this means that research into first generation processes should be continued and receive fresh support from European research agendas and that the quota system for producing sugar in the European Union should be revised in order to enable increased production of these feedstocks for industrial uses”.

In conclusion the two scientists of the nova-Institut ask for “a level playing field between industrial material uses of biomass and biofuels/bioenergy in order to reduce market distortions in the allocation of biomass for uses other than food and feed”.

Last May Carus and Dammer, together with Roland Essel (nova-Institut) and Andreas Hermann (from Öko-Institut, a leading European research and consultancy institute working for a sustainable future, based in Germany) published another paper focused on the misallocation of biomass in Europe: “Proposals for a Reform of the Renewable Energy Directive (Red) to a Renewable Energy and Materials Directive (Remd)”.

This paper is a comprehensive analysis of hurdles carried out by the four authors and shows – from their point of view – that the Red (Renewable Energy Directive), which will in future be associated with the Fqd – Fuel Quality Directive 9870 – in the transport sector, is one of the main causes of the longstanding and systematic discrimination between material and energy uses. “The Red – they write – hinders the development of material use and therefore that of the whole biobased economy. Unfavorable framework conditions combined with high biomass prices and uncertain biomass supplies deter investors from putting money into biobased chemistry and plastics – even though these would produce higher value and greater resource efficiency”.

“Misallocation of biomass” is the right phrase according to Carus and collegues, since this is blocking “higher value material uses like chemicals and plastics from coming to fruition. Therefore, Red-linked developments on the ground will have a considerable impact on the availability of biomass for the materials industry”.

As far as nova-Institut’s concerned, Europe needs a new political framework for the most efficient and sustainable utilization of biomass. Five years ago this was a worldwide problem – today it is mainly a problem for Europe. In America and Asia the political framework for biobased chemicals and plastics is much more favorable than in Europe. Accordingly, most of the new investments are going to USA, Canada, Brazil, Thailand, Malaysia and China.

“The reform proposal – the authors write – calls for an opening of the support system to also make biobased chemicals and materials accountable for the renewables quota of each Member State. The basic idea is to transform the Red into a Remd, Renewable Energy and Materials Directive”. The paper does not intend to establish a new quota for the chemical industry. Instead, it proposes that the material use of a biobased building block such as bioethanol or biomethane should be accounted for in the renewables quota the same way as it counts for the energy use of the same building block, e.g. fuel. Other building blocks, such as succinic acid, lactic acid, etc. could be accounted for based on a conversion into bioethanol equivalents according to their calorific value. Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions could also be the basis for such a conversion.

Finally, last October Carus, Dammer and Essel published on the same issues a new policy paper, whose title is “Options for Designing a New Political Framework of the European Bio-based Economy. nova-Institute’s contribution to the current debate”.

“The bioenergy and biofuels sector – according the nova-Institut – finds itself in troubled waters; many member states of the EU are not on track to meet the targets set out in the ‘Renewable Energy Directive (Red)’ and investments are stagnating. Political and public debates focus more on the effects on global food prices, pressure on ecosystems, and direct as well as indirect land-use change, rather than previous growth and future opportunities and investments. This is partly due to the fact that the whole sector (with some exceptions in the wood heating market) is strongly dependent on incentives. If those are reduced, many companies might face bankruptcy and new investments will stop – as can already be witnessed in many member states.

The material use of biomass presents an alternative to energy use. It can create much more added value per tonnes of biomass, innovation, employment and investment and – if done right – can contribute to the economically and ecologically viable future of the European Union. The current framework, however, focuses only on the energy sector in terms of market instruments; biobased materials and chemicals are only considered in research policies without any widespread application of novel biobased materials so far”.

You can download the three papers here: http://bio-based.eu/policy/#top

Image: © Valery Kraynov / Shutterstock