For Europe, 2014 was supposed to be the year of the circular economy: a new paradigm to project development models for society and industry from now to 2050. Those hopes were doused at the end of last year by the new European Commission under Jean-Claude Juncker, who decided to cut a long list of programmes believed to be ineffective or too expensive. Unfortunately, the circular economy package was among them.

However, in 2015, the disconcerted reactions of stakeholders and the disapproval of many member states forced the Commission to review its position, and it subsequently declared that the withdrawal of the first circular economy package was in fact designed to make room for the proposal of a broader and more decisive strategic initiative.

Is that really the case? What is certain at this point is that the Commission’s first package contained many holes and focused primarily on waste management, with little or no concern for all the other fundamental components of this new economic paradigm, such as remanufacturing, the sharing economy, or the bioeconomy.

Remanufacturing

Remanufacturing is a model based on processes organized and optimized to transform old products – whether used or discarded – into new ones, restoring them to their same or in some cases an even higher level, while providing warranties for their use to consumers. Several European countries have invested heavily in remanufacturing. For example, the United Kingdom has a plan to increase sales in this sector from the current 3.4 billion euro to 7.8 billion euro by 2030, a development that would lead to the creation of at least 20,000 new jobs.

With this context in mind, a conference was held last June, where the European Commissioners Frans Timmermans and Jyrki Katainen solemnly pledged to make a more resolute commitment in support of the circular economy, calling it a “fundamental strategy” for the development of the continent.

Thus Brussels has resumed its intensive efforts to put forward a Circular Economy package, which should be ready by the end of the year. But this remains to be seen. However, expectations are higher this time around because investment in the circular economy will have to sustain the development of the European industry and at the same time contribute to achieving the goals that will emerge from the COP21 conference in Paris on the fundamental challenges posed by climate change.

The Circular Economy: The Only Possible Alternative

But what should we expect, exactly? The experts working on programmes in support of the circular economy begin by noting that, at present, around 90% of European manufacturing revenue (without even considering manufacturing worldwide) come from linear processes of procurement, production, consumption, and discarding of waste.

There is, however, widespread acknowledgment – in words if not yet in deeds – that the only real option to provide an opportunity for future generations lies in the rapid transition to industry and manufacturing based on the circular economy: encouraging businesses to rethink production cycles in such a way that they eliminate the concept of waste with processes that maximize the reuse of products and materials through disassembling and recycling.

Such processes will have to distinguish between the different issues that surround consumables and durable goods. With respect to the former, the EU intends to push the use of natural and non-toxic materials that can be safely reintegrated into the biosphere. For durable and semi-durable goods, however, the emphasis will be on ensuring very high rates of reuse and recycling, both to prevent their components from potentially damaging the environment and to maximize efficiency in the use of raw materials.

The competitive advantages that the experts in Brussels seek to exploit through the repositioning of European manufacturing are thus closely linked with the goal of decoupling the extraction and use of natural resources – which has risen from 12 billion tonnes in 1980 to 22 billion today – from the economic growth necessary to guarantee the continent’s continued development and prosperity. This is an enticing prospect, which would allow Europe to tamper the price volatility of critical raw materials, creating greater stability in key industries and reducing risk in terms of procurement. In economic terms, the Commission estimates that by 2025 savings in raw materials for manufacturing due to the circular economy could reach at least 14% of output, a percentage equivalent to approximately 400 billion euro. For Italian industry, this would represent a savings of at least 12 billion euro. Adoption of circular processes could also encourage the creation of new business chains, providing a stimulus to consumption and encouraging job growth.

European Industry Has Already Begun

In some ways, European manufacturers have anticipated Brussels’ move. Several leading industrial groups have already begun transitioning their own manufacturing and maintenance systems toward greater “circularity.” This is happening because the most innovative companies have understood that the adoption of manufacturing processes based on the circular economy encourages business growth and create value for shareholders. The most commonly employed strategies range from remanufacturing of end-of-life products, to the refurbishing of in-service products to fit into the sharing economy or zero-waste policies, all the way to the restructuring of production processes to work in symbiosis with their partners in the supply chain.

The European Commission has declared its intention to incentivize and speed up investments in businesses that adopt forms of the circular economy, privileging the most virtuous actors. We shall see if these intentions are transformed into concrete measures that can push this experimental phase towards a so-called “mainstreaming,” where the most widely adopted manufacturing processes will all be essentially based on circular economy concepts.

What the European “Package” Means for Italy

A solid package of measures to support the adoption of the circular economy would also be extremely important for Italy, where all the ingredients to do well are already in place but the culture of and investment in innovation are sometimes slow in developing. This is not a concern solely for this transitional phase, which must be carefully managed, but it also represents a risk in terms of Italian manufacturers’ ability to attract investment from abroad. In fact, global enterprises that have already committed to the circular economy could possess an extra incentive of their own to express skepticism toward Italy. It is thus urgently necessary for Italy also to begin creating a more favourable context for the development of new industrial processes inspired by the circular economy, eliminating the impediments that could well end up penalizing the country: starting with the deficit in skills within the worlds of business and government, and consumers’ scant sensitivity to environmental issues, all the way up to the lack of a holistic vision necessary to develop a modern recycling sector.

For this reason the circular economy package soon to be offered by the European Commission may provide the necessary tools to tackle and remove these current obstacles. Italy needs measures designed to favour businesses that invest in the design of products, services, and processes that demonstrate a systemic vision of innovation, with a particular focus on small and medium sized businesses. To this end, it will be important to identify them, study their strategies, and make available stimulus mechanisms that are both fair and effective. Incentives for businesses that commit to refurbishing in-service products, for example, maintaining ownership of the goods they sell in order to manage the end of their life cycle more effectively, in part through the introduction of financial services capable of responding to the specific needs of consumers. Furthermore, stimulus measures for the circular economy could be inserted into a much broader revision of fiscal policy to support the green economy and eco-innovation.

Disownership

The concept of disownership that resides at the roots of the emerging sharing economy represents one of the most innovative and interesting aspects of the circular economy. The sharing economy reduces the environmental footprint of manufacturing activities, creates jobs, and increases the value of human capital by turning the sale of goods into increased public use and access to services with value added. In this particular context the new business models that are based on the sharing economy create interesting job opportunities tied to the development of modern service networks, technical assistance, consulting, financial services, and logistics. In Europe and throughout the world there is a shift underway in consumer preferences toward access to services on a pay per use basis, as an alternative to permanent individual ownership of durable goods. This transition offers substantial advantages to businesses from the point of view of the productivity of their assets, in that it allows them to create economies of scale, optimize the use of productive and service infrastructure, and hire highly specialized personnel. Several European countries have led the way in this transition. Sweden, for example, is fine-tuning a 12 billion euro investment plan for the circular economy, which places an emphasis precisely on the idea of a society of sustainable services.

The Circular Economy and Waste

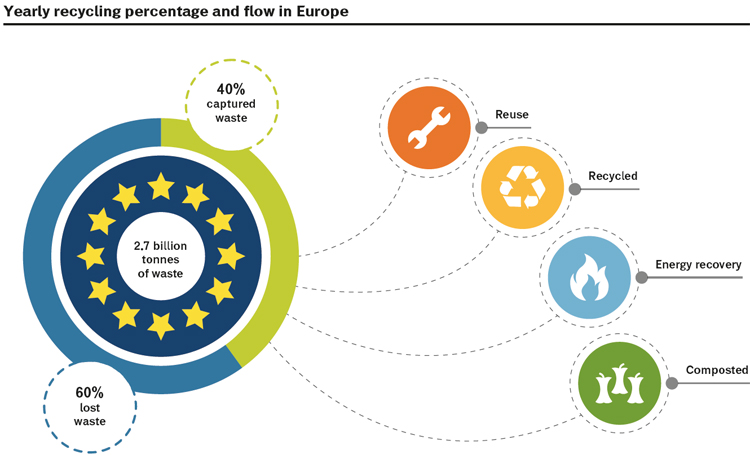

The circular economy package should also come up with innovative and organic solutions for products life cycle management. We know that Europe generates 2.7 billion tonnes of waste per year, and that only 40% of this waste – limited primarily to a few flows – is captured and processed for reuse, recycled to recover energy, or composted. There are thus significant margins for improvement, especially in Italy, where the situation is worse compared to the European average. Much waste escapes and end up being exploited abroad, and frequently, even when processes for recovery and recycling are in place, the raw materials are subjected to downgrading compared to what can be achieved today with the best technology available. Italy’s collection systems are in general expensive and inefficient, and do not help businesses to abandon traditional linear manufacturing processes or the treatment of finished products recovered after consumption. The Commission is assessing the possibility of introducing further simplifications to encourage increasing efficiency in collection systems, integrating them with upstream industries that make use of recovered components and raw materials from products at the end of their life cycles. Another topic Brussels intends to address is that of the development of professional networks specializing in the refurbishing of end-of-life machines that can be returned into production cycles for further use, thus avoiding the creation of waste and encouraging the development of new technical skills that can also be advantageous in terms of job creation.

We thus expect that the circular economy package will contain more effective strategies than those of the past with respect to encouraging demand for materials from the reuse and recycling of end-of-life products. By now it is clear to the experts on the Commission that the generation of demand by industrial chains downstream from production processes that generate scrap with the potential to be transformed into resources for reuse, is perhaps the best way to feed a virtuous cycle inspired by the circular economy. It is not a coincidence that in the last 24 months, Europe has witnessed the birth of several enterprises that have created brokerage models able to connect supply and demand for secondary raw materials or end-of-life products, creating benefits for the market and significant profits for investors. From this perspective, the new package of measures will seek to encourage the creation of new industrial chains based on a greater integration of enterprise on a Europe-wide scale, exploiting modern information and communication technologies more efficiently to reduce asymmetries in knowledge that can throttle trade and the development of cooperative processes.

European Funds for Innovation and Skills Development

It is imperative that the European strategy for the circular economy fully exploits the available assets in European funds for eco-innovation (Horizon 2020 and other structural funds) in order to support the investment necessary to create a critical mass in certain high-profile industries. It is worth emphasizing how, here, Italy possesses several strong points that could be exploited, which could allow the country to pursue leadership positions on the international level if they can be sustained by targeted investments in innovative businesses. It would thus behove Italy to focus on very specific skills in areas where it has a real opportunity to step forward and where contemporary Italian industries already appear to possess a real vocation. One might, for example, encourage the development of hydrometallurgy and biometallurgy for the recovery of precious metals and rare earths as an alternative to the great pyrometallurgical plants of Northern Europe. These plants employ innovative technologies with low environmental impacts (in comparison to the “old” technologies that work with very high temperatures), an area where Italy could play an important role. From this point of view it would appear important for Italy to represent itself in Europe with a clear vision, submitting robust and credible project proposals to pursue the necessary funding. In this realm, one might identify certain “champions” that are capable of leading a network of partners toward the realization of a new industrial system reinforcing the integration of the circular economy.

The new European circular economy package will almost certainly focus on the development of entrepreneurship and a culture of innovation through the support of more decisive interventions regarding education both theoretically and in the field. As previously noted, the Commission is well aware that the lack of skills and professional development in government and enterprises hinders a brake on the adoption of innovative models of circular economy.

Simplify to Innovate

Let us hope, then, that the package from Brussels manages to modernize the regulatory environment. In modern economies, the environment represents an essential resource to be protected, but not solely and not especially through a formal approach of binding agreements, compliance rules, and other onerous obligations. Rather, we must understand how to measure, in a more precise and efficient way, environmental externalities (environmental costs tied to the use of ecosystems by private parties), penalizing those who do not act to reduce them and incentivizing those who manage their business in such a manner as to mitigate their impact on the ecosystem. Today, such efforts are very often undermined by a rigid and obsolete regulatory framework, which sees “waste” as an exclusively environmental problem and not as an opportunity to create value throughout the manufacturing process.

A Question of Priorities

As we await the details of the circular economy package, which will acknowledge the input of consultations with stakeholders (a process that just concluded), it seems that the time has come for the Commission to define certain priorities, indicating which high-potential sectors Europe should focus on. With respect to goods with lengthy life cycles (construction and infrastructure, for example), one might undertake interventions with greater potential over the long term, while in the short term the most interesting initiatives could concern consumer durables, particularly more complex products like machinery, electrical appliances and electronics, furniture, machine tools, motors and vehicles. The annual sales attributed to these types of product are approximately 2.6 billion euro, testifying to the importance of the recovery of raw materials from them at the end of their life cycle. If we assume that the cost of raw materials makes up an average of 25% of a product’s price, we might expect the economic value of the theoretical complete recovery of such materials to amount to at least 500 billion per year, a figure that is certainly food for thought for the Commission’s decision makers. Only time will tell...