The picture of a cemetery for refrigerators – cannibalised and discarded in an abandoned industrial site just outside Rome, a stone’s throw from Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli – perfectly describes the effect of today’s circular economy black market piranhas. They feast on anything valuable (compressors and metals) and spit out the rest (the polyurethane body and refrigeration gases), wherever they find room. In 2013 alone, Rome’s Municipal police discovered around thirty sites like this. And, its not just Rome: in other areas of Italy – such as Modena – more than fifty were identified.

In this orgy of waste traffickers, WEEE is undoubtedly one of the most desirable types of waste. Why? It has a high intrinsic value, legal systems for its management struggle to intercept it due to the countless channels through which it passes, and because of the impressive and increasing quantities we continue to produce.

According to the most reliable estimates, in Europe we produce between 9 to 10 million tonnes of WEEE per year. In contrast, according to the WEEE Forum (the international association that unites Europe’s main e-waste producer responsibility organisations), only 3.5 million tonnes are collected per year. The rest ends up on the black market. In Italy, things are even worse: WEEE going through informal channels exceeds 65%.

According to Lega Ambiente’s dossier “Pirati dei Raee” (WEEE Pirates), published in collaboration with Centro di coordinamento Raee in 2014 (Centre for the coordination of WEEE), in Italy, about 74% of WEEE ends up in illegal markets and between 2009 and 2013, nearly 300 illegal WEEE dumping sites were discovered. Striking data that unfortunately seems to be confirmed by other figures. For example, the surprising coincidence between 2016 figures for WEEE seized by police at Italian border controls (due to illegal exporting), and the quantity of WEEE collected by the Italian municipality network in the same period (Ispra 2017). Incredibly, the two figures match perfectly and amount to approximately 235 million tonnes. This does not mean that all WEEE collected by Italian municipalities ends up being exported illegally, but rather that there is a black market, equalling the official one and swarming with WEEE piranhas. Furthermore, this doesn’t even take into account the amount of WEEE circulating in distribution supply chains, which is actually the majority.

In addition, the figures for 2017 do not add up and WEEE amounted to over 38% of waste seized by the Italian border protection agency. The drain continues.

Perhaps, in order to understand how the black market operates, we must briefly describe how the legal system works in Italy. The chosen model of governance is the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) where manufacturers/retailers are directly responsible for collecting end of life products. To comply with this requirement, manufacturers usually create consortiums (private law entities) which then become the main actors in ensuring the proper functioning of the legal mechanism. In the WEEE sector, as many as 15 consortiums were set up, thus making it necessary to create a WEEE Coordination Centre (Cdc Raee), which is mainly in charge of coordinating the individual entities, while becoming a point of reference for the entire network. Who funds the EPR system? The famous eco-contribution paid by consumers when they buy a new product.

Since there is no legal requirement for municipalities or dealers to give WEEE to collective Systems, this has practically led to the creation of at least two markets: one managed by Cdc Raee and one managed privately, where only market rules apply. This is because both municipalities and retailers can sell their WEEE to the highest bidder (as long as they have a WEEE treatment authorisation). While the Cdc Raee System (despite its many bottle necks along the supply chain) can offer some degree of supply chain traceability and an annual census on collected and treated quantities, the same cannot be said for channels operating outside this system, which, in all likelihood, represent the largest market share.

As Giorgio Arienti (Ecodom DG and Cdc Raee President) explains, “When consumers buy a new fridge, 9 times out of 10, they throw the old one away – it is a replacement market – but Collective schemes, members of Cdc Raee, only receive 5. The same is true for washing machines, where only 3 out of 9 are intercepted. Which begs the question, where do these home appliances end up, and above all, in whose hands?”

The truth is that in this sector there are too many famished sharks, both on the supply and demand side, trying to systematically hide the costs of treatment processes. If on the one hand, WEEE sent on by businesses and Municipalities to be handled by the Cdc Raee System is regulated by public national programme agreements stating, for instance, that for each tonne of Category 1 waste (large household appliances cold and non cold) handed over to collective systems by waste municipalities and retailers, they receive €50, and €100 for each tonne of Category 2 (Small household appliances); on the other, it is very difficult to know the economic agreements and extent of compliance with environmental regulations, guaranteed by those operating outside this system.

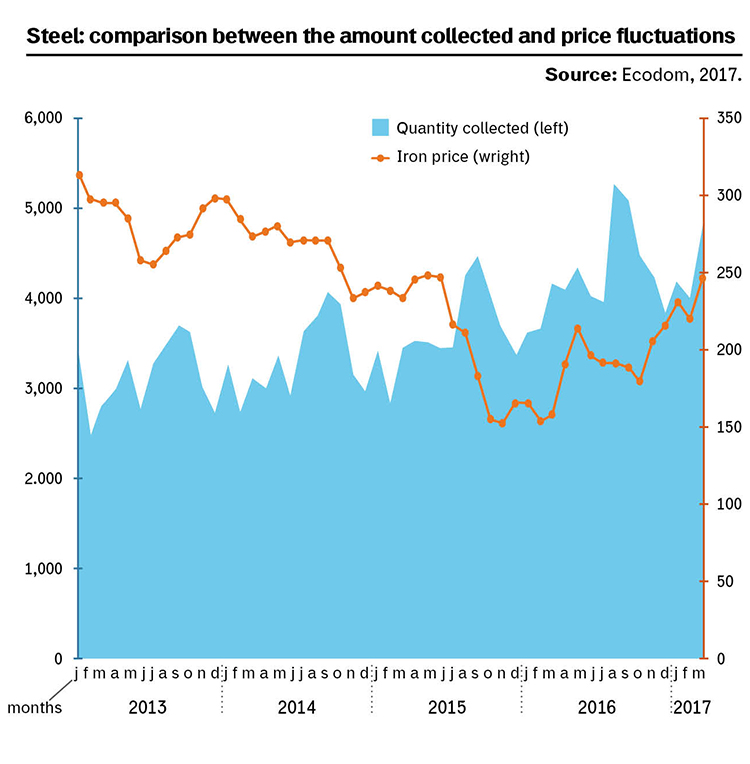

One thing is for sure, the illegal market thrives in the loop-holes of legal models and it is heavily influenced by raw material price trends on the international market. For instance, when the price of iron or copper increases, flows to Cdc Raee (and vice versa) decrease in accordance, while those on the free (and also illegal) market increase. As Italian customs officers and police know only too well.

One last observation on municipalities’ waste collection systems. They are often the victims of raids, on their communal recycling centres and depots, that are carried out to feed illegal markets. In fact, it is not rare to see groups of people loitering outside communal recycling centres to spot potential customers even before they enter the site. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that companies operating legally experience shortages of materials to process.

And, what about the eco-contributions paid by citizens and consumers? Collected by businesses, they are then paid to manufacturers and then passed on to collective systems to fund the share of WEEE they manage. Whereas remediation activities and social and environmental degradation caused by illegal disposal, are paid by all citizens, with no exception

Probably, a shortfall in the general system of governance is down to the lack of synergy between the management of Municipalities and distribution systems. They do not communicate with each other and each of them goes their own way, even passing the blame onto each other. This has led some European countries to understand that this is where the problem lies. Thus, thanks to particularly willing administrations, some network initiatives have been put in place to intercept as much WEEE as possible (especially small items that are difficult to catch) and meet the EU’s ambitious collection targets (65% by 2019).

In Germany, in the Saxony-Anhalt Region, and more precisely in Halle (Saale), they have attempted a mixed waste collection system, integrating traditional collecting centres (consignment model) with mobile units for the collection of hazardous waste (collection model) and 34 depots for containers to intercept very small WEEE items (consignment model). Together with the extension of operating hours for consignment in collection centres (open 80 hours per week, when the average in Germany is about 60), this synergy has boosted the collection performance.

Similarly, in the Swedish town of Gävle, roughly 200 km north of Stockholm, they have “seen the light” enlarging collection points in all shops and signing agreements with the Coop network. Good communication with citizens, more frequent emptying of containers, and guaranteed fast and efficient collection from retailers, by paying a small contribution (about €20), has done the trick. Public and private sectors teamed up: in 2013, over 1 tonne of small electrical and electronic devices ended up in the Municipality’s virtuous network, preventing them from finding their way into informal channels.

Small examples of strategic forward thinking serving the community and a win-win situation thanks to networking; that leaves only waste thieves behind. While in Italy they continue to thrive.

Legambiente, “I pirati dei Raee” (WEEE Pirates); www.legambiente.it/sites/default/files/docs/raee_dossier_i_pirati_dei_raee_02.pdf