Top universities and research centres, innovative start-ups and large companies, clusters, pilot plants, a cutting-edge logistic system and agriculture and chemistry as the economy’s driving forces. There could not be better conditions to develop the bioeconomy. The Netherlands, boasting all such conditions, will hold the Presidency of the European Union, which will host the Fourth Bioeconomy Stakeholder Conference from 12th to 13th April in Utrecht.

Top universities and research centres, innovative start-ups and large companies, clusters, pilot plants, a cutting-edge logistic system and agriculture and chemistry as the economy’s driving forces. There could not be better conditions to develop the bioeconomy. The Netherlands, boasting all such conditions, will hold the Presidency of the European Union, which will host the Fourth Bioeconomy Stakeholder Conference from 12th to 13th April in Utrecht.

Between Amsterdam and Rotterdam the bioeconomy is a well-established concept. It is based on two elements: a medium to long-term strategy “Hoofdlijnennotitie Biobased Economy” (2012) where the sector is at the core of national innovative policies and sustainable growth. Public/private partnerships also bring together – aided by the government – companies, non-profit organizations and research centres (2011 Manifest Bio-based Economy, and 2012 Innovation Contract for the Bio-based Economy).

Considering the impending exhaustion of the Dutch gas reserves (they will only last for twenty more years or so, according to experts), The Hague’s government is committed to finding alternative energy sources. The Netherlands boast a considerable level of competence in the field of renewable energy and are world leaders. The government strongly supports the sector and put it amongst the nine top sectors in the industrial policy’s planning set up in February 2011 by the Ministry of Economic Affairs.

The objective is to achieve a 14% renewable energy production by 2020 and 16% by 2023, thanks to a strategic national programme geared towards three aspects: energy saving, development of renewable sources and efficient use of fossil reserves.

But The Netherlands are also an important hub for biotechnologies, where the government aims for a world leading role by 2025. For this reason, the biotechnological sector has become one of Holland’s priority sectors. In 2013, total funding amounted to about €310 million, of which 143 from private capital and 167 from public funds.

But in the Netherlands, the agribusiness holds the lion’s share, with an added value of €42 billion in 2014 and 641,000 employees. The sector boasts a high innovation level, not least for the close connection with the Agricultural University Wageningen, the world’s most authoritative institution for research and education in the field, a point of reference for Europe’s bioeconomy.

Unilever is half Dutch and half British. The giant owning some of the most famous food brands and founder – together with Coca-Cola, Nestlé and Danone – of Bioplastic Feedstock Alliance (BFA) aims to use bioplastics in food packaging. Again, a Dutch company provides the necessary technology: Avantium, Royal Dutch Shell spin-off, which boasts Capricorn Venture, a Belgian Fund, amongst its top investors. The patented technology is called YXY, thanks to which it will be possible to replace PET with PEF (Polyethylene Furanoate). According to Tom van Aken, Avantium CEO, “YXY is able to create new biobased plastic materials with extraordinary functional properties at a competitive cost, perfectly integrating the production process with existing supply chains.”

Unilever is half Dutch and half British. The giant owning some of the most famous food brands and founder – together with Coca-Cola, Nestlé and Danone – of Bioplastic Feedstock Alliance (BFA) aims to use bioplastics in food packaging. Again, a Dutch company provides the necessary technology: Avantium, Royal Dutch Shell spin-off, which boasts Capricorn Venture, a Belgian Fund, amongst its top investors. The patented technology is called YXY, thanks to which it will be possible to replace PET with PEF (Polyethylene Furanoate). According to Tom van Aken, Avantium CEO, “YXY is able to create new biobased plastic materials with extraordinary functional properties at a competitive cost, perfectly integrating the production process with existing supply chains.”

Another important Dutch company is Friesland Campina, one of the world’s five largest dairy companies (€11.3 billion annual turnover), which is working on a new biobased cardboard for drinks produced with a material obtained from certified organic waste to add to another existing renewable one. The company is committed to reducing its carbon footprint by a further 20% of that generated with current packaging.

When it comes to chemistry, large companies such as Royal Dsm, AkzoNobel, Royal Dutch Shell, Corbion are often mentioned. These companies are investing large capitals in the bioeconomy. In the Netherlands, the chemical industry is traditionally favoured by both the availability of necessary raw materials and an excellent multimode transport system using ships, lorries, trains, oil and gas pipelines. According to the data by VNCI, the Dutch trade association, in 2013 the sector’s net sales volume generated approximately €57 billion (51 billion excluding pharmaceuticals). Still in 2013, overall exports reached €75 billion, while imports were €52 billion (+3% compared to 2012), with a positive balance of €23 billion.

Dutch companies are characterized by the formation of “groups” enabling the presence of important economies of scale, mainly with regard to transport costs and disinvestments in raw materials, thanks to the excellent infrastructure developed around the port of Amsterdam, Delfzijl, Flushing-Terneuzen, Heerlen-Geleen and Rotterdam-Moerdijk.

It is no coincidence that Dutch ports are the bioeconomy’s major protagonists. Rotterdam stands out amongst them and is determined to become the logistic hub of biomass used in Europe and together with AkzoNobel is involved in a project experimenting with the possibility of using urban solid waste for the production of biofuels and biochemicals, using Canadian Enerkem’s technology.

Furthermore, two giants of the new economy using bio-based resources as raw materials have their headquarters in the Netherlands, namely DSM and Corbion Purac. Both companies are developing biobased succinic acid through joint ventures with two other European chemical colossi. DSM with French Roquette created Reverdia, producing its own Biosuccinium in the Italian plant in Cassano Spinola (Piedemont). Carbon Purac with German BASF formed Succinity GMbH, with its production plant in Montmelò, Spain.

Through another joint-venture with the US POET, DSM started the production of an advanced fuel in the US: in September 2014, in Iowa, they opened their first commercial plant which using agricultural waste: “A historic day – as Feike Sijbesma, DSM’s CEO defined it – which marks the passage from the fossil to the biorenewable era.”

In fact, the Netherlands know how to best exploit their historical bent for internationalization. The great willingness of local clusters to collaborate with foreign partners is a proof of this.

In fact, the Netherlands know how to best exploit their historical bent for internationalization. The great willingness of local clusters to collaborate with foreign partners is a proof of this.

Last October in Brussels, during the European Forum for Industrial Biotechnology and the Bioeconomy, Biobased Delta launched Intercluster 3BI, together with French Iar-Pole, German Bioeconomy Cluster in Halle and British BioVale. It is a partnership amongst the four major European clusters that includes biorefineries for converting biological resources into food, feedstuff, materials, chemicals and fuels. Their drive is to share research, development and implementation of new highly technological approaches to convert biomass, renewable raw materials and waste into added-value products and applications.

Biobased Delta is a cluster based in the Southeast of the Netherlands; it promotes itself with a slogan combining the country’s strengths: “Agriculture Meets Chemistry”. Agricultural residues are seen as the base of the biobased industrial innovation. Especially for chemistry because the Dutch cluster is part of the world’s biggest cluster created by Antwerp, Rotterdam and Ruhr Regions.

Biobased Delta also harbours Biorizon, a shared research centre (that works in partnership with Bio Base Europe, a bioeconomy educational centre based in Ghent), specialized in the development of technologies for the production of aromatic compounds derived from renewable sources to be used in high-performance materials, chemicals and coating. They have an ambitious goal: to become in the next years one of the world’s top three research centres in this field. To this end – besides having started an intensive activity of international relationships with Brazil and Canada – a memorandum of understanding was signed in 2014 in Reims at the Iar-Pole headquarters by Willem Sederel, Biobased Delta CEO, and French President François Hollande in order to facilitate French industry’s access to Biorizon.

But there is more. Amongst the Dutch cluster’s initiatives it is worth mentioning the Green Chemistry Campus, a business accelerator for innovations using renewable sources. In the headquarters of Sabic Innovative Plastics (a company controlled by Sabic, Saudi Arabia’s petrochemical colossus) in Bergen op Zoom, small and medium enterprises, research centres, universities and government institutions work side by side in a welcoming innovation atmosphere to develop new technologies, strictly biobased, through the utilization of waste flows from food and agriculture.

Another international project is Big-C, the BioInnovation Growth mega-Cluster, an international smart specialization initiative aiming to transform the mega cluster created by the Flemish Region of Belgium, the Netherlands and North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany) into a world leader of the bioeconomy. This is not only the largest chemical cluster in Europe, but it is also a very important agriculture and silviculture cluster. Above all, it produces the highest levels of CO2 emissions and the largest quantity of urban waste of the entire Old Continent. Here, the bioeconomy combines perfectly with the circular economy paradigm.

Big-C is supported by the BE-Basic Foundation, the umpteenth public-private partnership coordinated by the Deft University of Technology with the aim to support R&D in new sustainable bioproducts. At the start, at the begging of 2010, it received funds for €120 million by the Dutch government to support its activity, in this case as well strongly oriented to internationalization. Several European universities collaborate with BE-Basic, including Imperial College London and Dortmund University of Technology. It also has partnerships in Malaysia, Brazil, the USA and Vietnam.

Big-C is supported by the BE-Basic Foundation, the umpteenth public-private partnership coordinated by the Deft University of Technology with the aim to support R&D in new sustainable bioproducts. At the start, at the begging of 2010, it received funds for €120 million by the Dutch government to support its activity, in this case as well strongly oriented to internationalization. Several European universities collaborate with BE-Basic, including Imperial College London and Dortmund University of Technology. It also has partnerships in Malaysia, Brazil, the USA and Vietnam.

Bioprocess Pilot Facility is the flagship of the project, a pilot plant made available to start-ups and big companies for the industrial scale-up of processes using biological resources. Establishing whether an idea developed in a laboratory can really become a new bioproducts is indeed a very important step. Bioprocess Pilot Facility allows companies to share the investment required for the plant. “Investing in a pilot plant used only by one company” Arno van de Kant, BPF Business Development Manager, argues, “can be very costly (€15-20 million) and, something perhaps even more importantly, there is a need for qualified process experts and operators able to improve the process.”

For the Netherlands, the development of the bioeconomy is strategic. “Taking into consideration our strengths in the chemical, agribusiness and logistic sectors,” Mr van de Kant claims, “we are trying to be the first to successfully implement a sustainable circular economy.”

BioEconomy Utrecht 2016, www.bioeconomyutrecht2016.eu

Bioplastic Feedstock Alliance, bioplasticfeedstockalliance.org

The Dutch post system (PostNL) boasts a long tradition of issuing communication or graphic high-quality stamps, famous the world over.

In this article:

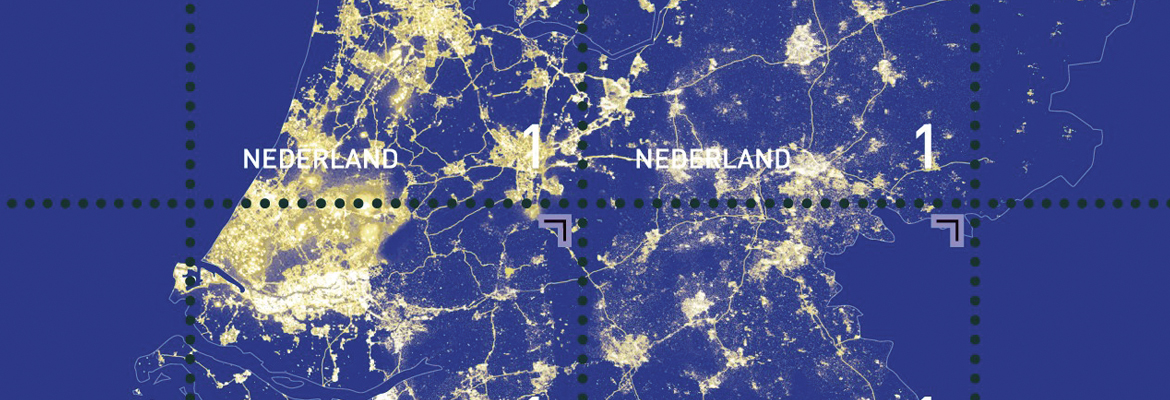

- a complete sheet of stamps by Daan Roosengaarde, a puzzle representing the Netherlands as a network of lights seen from space;

- a stamp designed by Tod Boontje Studio;

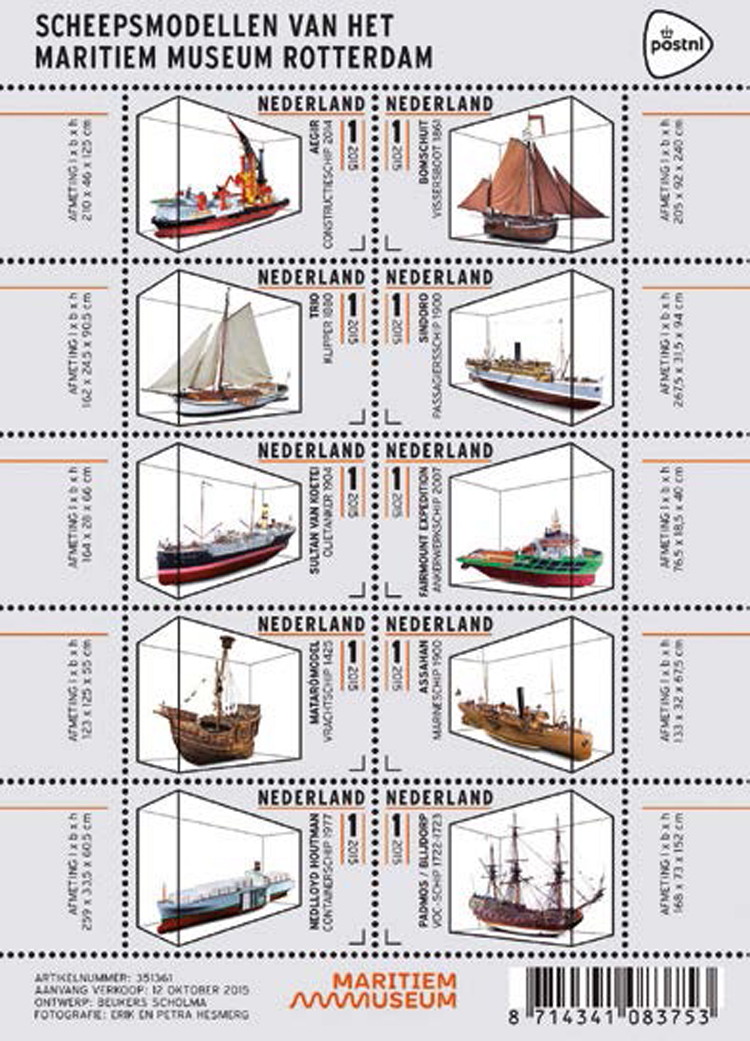

- a sheet of commemorative stamps celebrating Rotterdam’s Sea museum;

- stamps designed by Irma Boom for Rijksmuseum in 2013 where every stamp represents parts of the work of art that can be completed sticking on the side the next stamp

- from the series Nederlandse Molens (2013) by Loost Veekkamp, a graphic designer and illustrator;

- from the series Kinderpostzegels (2013) by Anton Corbijn, photographer and film director.

See the website: www.iconenvandepost.nl

Interview with Yvonne van der Meer, head of the Biobased Materials department of Maastricht University.

Interview with Yvonne van der Meer, head of the Biobased Materials department of Maastricht University.

Edited by Mario Bonaccorso

Dutch Bioeconomy: From Biomass to Business

“The Dutch strengths in industry and knowledge infrastructure in the top sectors chemistry and agriculture & food are a good starting point for the development of a flourishing biobased economy. Almost all Dutch Provinces have developed biobased economy programs to exploit regional opportunities in a national context.” To say this – in this interview with Renewable Matter – is Yvonne van der Meer, head of the Biobased Materials department of Maastricht University. With her we talk about the Dutch bioeconomy: The role of biomass, logistics and universities. “The value chains of the biobased economy – she says – are being established and complex logistic issues need to be addressed to create viable business cases.”

The Netherlands was one of the first countries in Europe to adopt a national strategy for the bioeconomy. What are the main aspects of this strategy? And how has a strategy facilitated the development of the bioeconomy?

“The national strategy identifies that the transition to a sustainable biobased economy is largely based on internationally distinctive knowledge and innovation. A large number of industries and research organizations from different sectors and disciplines have jointly developed an innovation contract ‘Green growth, from biomass to business.’ It describes how to build on current strengths in the Netherlands to gain economic advantage and competitiveness from the transition to a biobased economy. The transition needs testing of new concepts, strategic alliances for further development and upscaling to commercial exploitation. In 2015 a national research agenda ‘Biobased Economy 2015-2027’ was presented by the top sectors chemistry, agro & food, and energy. Top sectors are collaborations of industry, science and government.”

From your point of view, what differentiates the Dutch bioeconomy from others European bioeconomies?

“The top sectors make use of a so-called triple helix approach where industry, science and government cooperate to foster sustainable economic growth. This is typical for the Dutch innovation system: joint agenda setting and cooperation in innovation projects are promoted, resulting in public private partnerships. The Dutch strengths in industry and knowledge infrastructure in the top sectors chemistry and agriculture & food are a good starting point for the development of a flourishing biobased economy. Almost all Dutch Provinces have developed biobased economy programs to exploit regional opportunities in a national context.

“The Brightlands campuses in Limburg (South East of the Netherlands) are prime examples of triple helix cooperation in food, health, smart services and materials. The campuses are supported by the Province of Limburg and are innovation hotspots where public and private partners jointly develop research and innovation programs, R&D and piloting infrastructure as well as teaching programs to educate the innovation leaders of the future.”

The Netherlands aims at being the logistics hub for the European bioeconomy. What is the role of the logistics system in the development of the bioeconomy? Importing biomass from far areas does not mean making less ecologically sustainable the bioeconomy?

“Personally I do not believe in a sustainable bioeconomy where biomass has to come from distant regions. The production routes of the biobased economy are still under development and it is a real challenge to create a coherent sustainable and efficient production system. Such system may have a much smaller scale than the current ones. The value chains of the biobased economy are being established and complex logistic issues need to be addressed to create viable business cases. I see the bioeconomy as part of a circular economy where new integral chains for life cycle of products will be developed that take into account repair, reuse and recycling. This calls for new materials and product concepts, but also for new logistic concepts, with potential big rewards in terms of sustainability.”

What is the role of Dutch universities in the bioeconomy?

“The Dutch universities contribute to the development of the biobased economy with science and technology development and knowledge & technology transfer. There are several public private partnerships, such as the Top Institute Food and Nutrition and the BE-Basic foundation. In our region Limburg, two institutes were recently launched with support of the Province of Limburg that focus on biobased materials and biobased building blocks, respectively: the Aachen Maastricht Institute for Biobased Materials, a joint institute of Maastricht University and RWTH Aachen University (Germany) and the Chemelot Institute for Science and Technology, a joint institute of DSM, Maastricht University and Maastricht University Medical Center, Eindhoven University of Technology and the Province of Limburg.

“Dutch universities also contribute to the bioeconomy by training the knowledge workers needed. As of 2015, Maastricht University offers an international 2-year Master Biobased Materials at the Brightlands Chemelot Campus. This unique multidisciplinary program has active industry involvement in the curriculum and uses problem based learning, a small scale student centered learning method.”

What kind of research are you doing at your University?

“The past years I have been working on setting up a new department Biobased Materials of Maastricht University in the industrial surroundings of the Brightlands Chemelot Campus in Geleen. Currently I am the director of the department, I am teaching three courses in our Master Biobased Materials and Bachelor program in natural sciences and I am setting up a research line on the assessment of the sustainability of biobased materials. The biobased economy is supposed to tackle societal challenges like climate change. However, are the biobased alternatives under development indeed solving these issues? And if not, how can present solutions be improved? Currently we are setting up a research group on this subject and we have obtained the first funds to start research activities, so I am looking for researchers to join my team at Maastricht University.”

In April, Utrecht will host the fourth European Bioeconomy Stakeholders Conference. What are the three main measures that Europe needs to foster the growth of the bioeconomy?

“For me it is important that the biobased economy does not only promote biofuels, since this limits the utilization of the biomass potential. There are sustainable alternatives for energy production, so biofuels are not the only option. It should become more attractive to use biomass in higher-value applications, like chemicals and materials, e.g. by promoting cascading systems. For the use of the full potential of molecules of biological origin, I would also like to see that the development of new biobased building blocks and new production routes are supported. Breaking down biomass to ‘drop in’ building blocks is beneficial for quick uptake by the market, but is not efficient from a resource and energy perspective. Lastly I would like to promote taking into account more environmental impacts than only carbon footprints. If a carbon neutral solution induces another sustainability problem, like (indirect) land use change, we are not developing a long-term sustainable solution after all.”

Interview with Tom van Aken, CEO of Avantium.

Interview with Tom van Aken, CEO of Avantium.

Edited by Mario Bonaccorso

United We Stand

“From an Avantium point of view, there is strong need for a European approach rather than a national approach, to avoid an inefficient scattering of knowledge and skills.

“Secondly, the bioeconomy would strongly benefit from coherent governmental policies. We are strong believers of ‘a level playing field’ when competing with the traditional fossil-based industries”. Tom van Aken talks to Renewable Matter. In this interview the CEO of Avantium, a spin-off of Royal Dutch Shell and one of the most dynamic and innovative European bioeconomy’s company, shares with us his idea of bioeconomy.

“If the EU – he says – believes in the fundamental need to transition from a petro-based to a biobased industry (see COP21), then governments need to put penalties on undesired behavior (tax on CO2) and/or reward desired behavior.”

The Netherlands were one of the first countries in Europe to adopt a national strategy for the bioeconomy. What are the main aspects of this strategy? And how has a strategy facilitated your business?

“Avantium operates a global business model and looks at region specific investment/support programs. For each region we assess the general support packages (ranging from subsidies, grants, to tax incentives, loan guarantee packages, investment funds, etc.). The largest program in the Netherlands that is specifically tailored to the NL Bioeconomy strategy is called SDE+, for which Avantium would qualify in case we decide a production unit in the Netherlands. Furthermore, there are a number of subsidy programs that Avantium qualifies for collaborations with universities and other development partners, specifically focused on biomass. These programs help us to (partially) fund the necessary ‘groundwork’ to see if there is a business opportunity.

Other programs outside the NL Bioeconomy strategy that we qualify for are related to R&D activities and technology development activities, such as WBSO and RDA.”

The Netherlands aim at being the logistics hub for the European bioeconomy. What is the role of the logistics system in the development of the bioeconomy? Importing biomass from faraway areas does not mean making the bioeconomy less ecologically sustainable?

“This requires a more specific approach to answer properly. Transporting biomass over a certain distance requires a tradeoff between the logistical costs and the economies of scale of the processing unit, and the impact on the ecological system. Also, one needs to consider the longer term business model, i.e. developing the technology may have different tradeoffs when compared to the industrialization of the technology.”

What are the projects Avantium is implementing in the bioeconomy?

“Avantium has developed a revolutionary production process, called YXY technology that enables the economic conversion of carbohydrates into (Furanics) green building blocks. The process is protected by a robust patent portfolio filed by Avantium. The process is a chemical, catalytic process that fits well with existing chemical production plants. YXY is a chemical, catalytic process: a fast, highly efficient and selective conversion of carbohydrates into Furanics building blocks such as FDCA. Avantium operates a pilot plant in Geleen, the Netherlands, where its YXY technology has been validated at 20 ton/year scale. We have publicly disclosed that we – besides YXY – are working on the projects Mekong (converting biomass to MEG) and on Zambezi (converting non-food biomass to glucose).”

From your point of view, what differentiates the European bioeconomy from the American one? Where is it easier to invest?

“Investing in certain regions or technologies is not necessarily a decision driven by ‘easiness.’ For example, the factor time plays an important role. A decade ago, the US had a strong support program in place for developing and commercializing biofuels. Today, the EU has a strong support program in place for developing and commercializing biobased chemicals and sustainable energy solutions.”

In April, Utrecht will host the fourth European Bioeconomy Stakeholders Conference. What are the three main measures that Europe needs to foster the growth of the bioeconomy?

“From an Avantium point of view, there is strong need for a European approach rather than a national approach, to avoid an inefficient scattering of knowledge and skills.

“Secondly, the bioeconomy would strongly benefit from coherent governmental policies. We strongly believe in ‘a level playing field’ when competing with the traditional fossil-based industries. If the EU believes in the fundamental need to transition from a petro-based to a biobased industry (see COP21), then governments need to put penalties on undesired behavior (tax on CO2) and/or reward desired behavior.

“Thirdly, building the bioeconomy will require a transition time, so we have to accept that we can’t solve all problems in one go, and that we have to accept some suboptimal solutions along the way. It also requires consistent policies that can withstand political changes over time.”