The circular economy concept is becoming increasingly widespread, but it is not easy to apply to the operational and everyday run of businesses. Indeed, by definition, the circular economy requires careful redesigning of a product life cycle. Its application has to overcome great barriers, especially in smaller companies due, on the one hand to partial awareness and knowledge of all different opportunities of saving, reusing, recovering and recycling of resources and materials; on the other, due to the difficulties in identifying and involving in this chain partners able to support the company in actions aimed at “closing” the loops, thus optimizing the use of resources while minimizing waste.

In this framework, the European Commission has intensified its commitment in this field, in particular with COM (2015) 614/2 allocating huge financial resources to this topic: European funds to support the necessary investments promoting a turnabout from a linear to a circular model.

This framework has offered Assolombarda the great opportunity, thanks to the technical support of GEO-IEFE Bocconi, to start a project to help partner companies acquiring awareness of the different possibilities offered by the circular economy. This is how the CERCA (Circular Economy – Una Risorsa Competitiva per le Aziende) project was created, with the aim of turning Circular Economy into a Competitive Resource for Companies (the meaning of acronym “CERCA” in Italian, editor’s note), ready to get involved and reconsider their processes and activities with a new critical approach.

The project has a threefold objective: helping companies identify opportunities through a check-up process and the ensuing definition of action plans and operational solutions at company level and within a specific value chain; promoting best practices; identifying barriers and obstacles to support their policies. This has meant forefront commitment of companies that have identified trial projects as well as opportunities and barriers due both to a specific case, to the sector and sometimes to the economic system in general.

Business case studies, together with a more academic analysis of literature, have been explored adopting an approach devoted to identifying and promoting certain business models, namely those deemed more efficient in adopting and managing circular economy strategies at company level. Following this logic, specific business models applying the circular economy to the operational run of companies were identified, sharing one or more common points with companies taking part in the CERCA project and presented below.

The Main Business Models

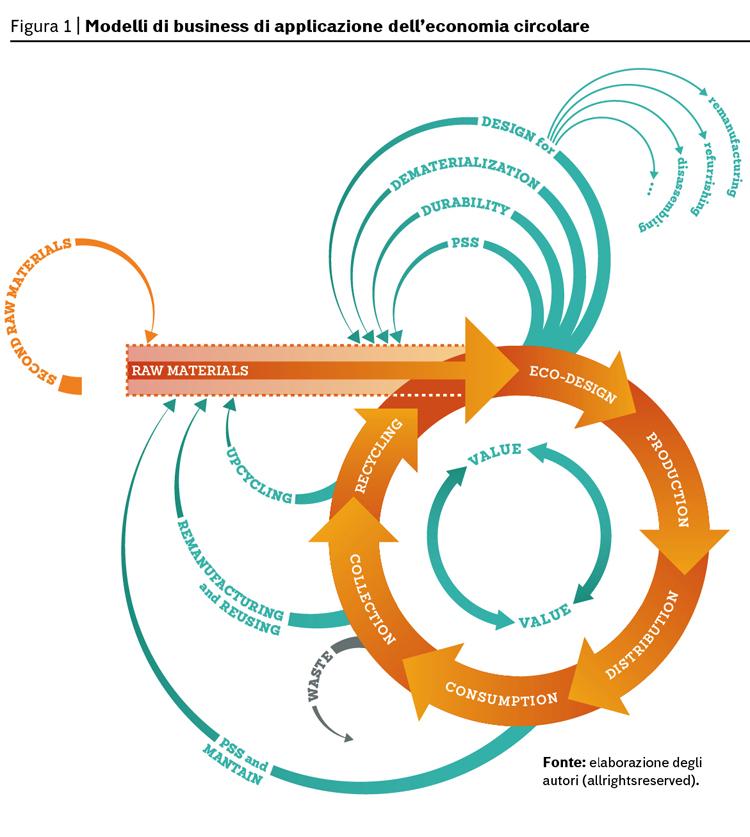

Amongst those characterizing many companies’ experience taking part in the CERCA project, four main business models emerge: dematerialization, remanufacturing, upcycling and durability, representing the different facets of implementing the circular economy at practical level (figure 1).

All these strategies – starting concept reassessment and product redesigning through all stages – explore innovative ways of managing the life cycle, from raw material mining to recovery and reusing methods.

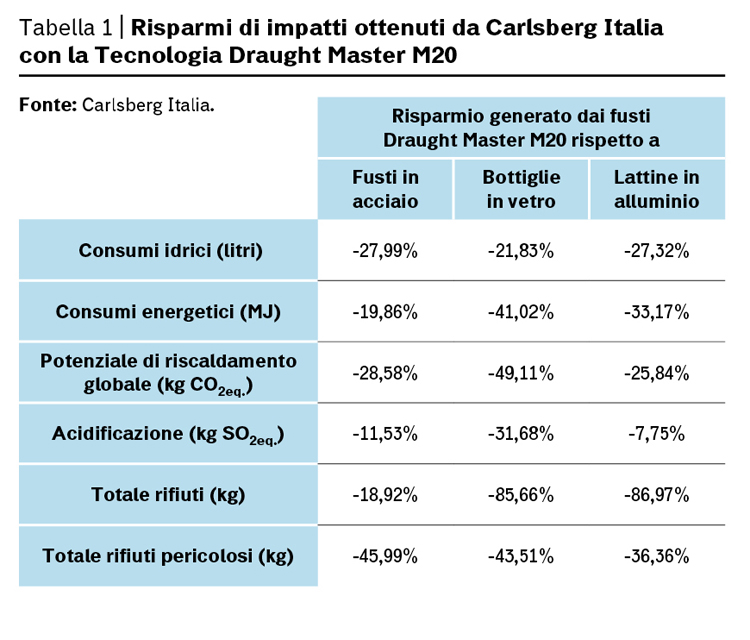

Carlsberg Italia represents the dematerialization model having revolutionized its beer tapping technique through the introduction of the DraughtMasterTM system, a radical innovation replacing the traditional steel cask with a recyclable PET one and allowing Carlsberg to do away with CO2 as a propellant for tapping. The aim of dematerialization is to use less material resources and/or in a better way and materials as production input and product components (“doing more with less”) and is based on innovation and rethinking of a product or its packaging, production and consumption cycles. The revolution of Carlsberg Italia’s tapping system, even before representing a dematerialization model, implements an inclusive strategic vision going beyond the simplistic approach where the circular economy is seen as a mere question of managing waste and end-of-life. Design innovation has an important impact on all upstream stages – it pays particular attention to supplying, process and product input and packaging – promoting environmental and economic sustainability, while downstream it influences logistic and modes of consumption.

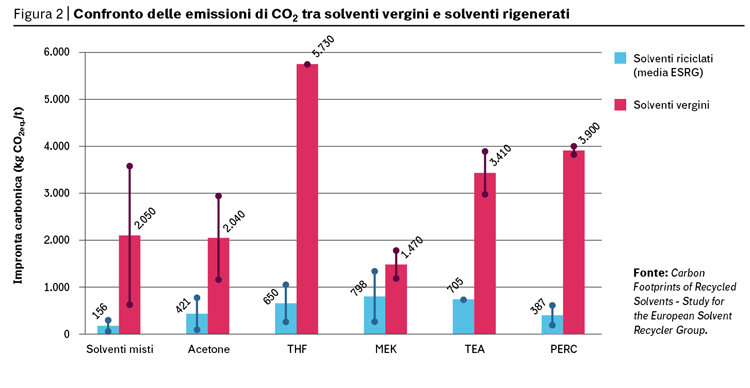

NitrolChimica represents an application model of remanufacturing, based on the logic of transforming “waste” into resource. The production of solvents is carried out through the regeneration of processing waste from different sectors where solvents are raw materials (pharmaceutical, chemical, cosmetics and automotive). The recovery of solvents manages to drastically reduce CO2 emissions compared to the production of the same substances from fossil sources while achieving excellent quality performances. Remanufacturing involves disassembling the used product and recovery in order to keep the same specifications of the original product: performances are at least equal or can be even better compared to those of the original use and for consumers the product thus manufactured not only conforms to technical and safety standards, but it is as good as a new product.

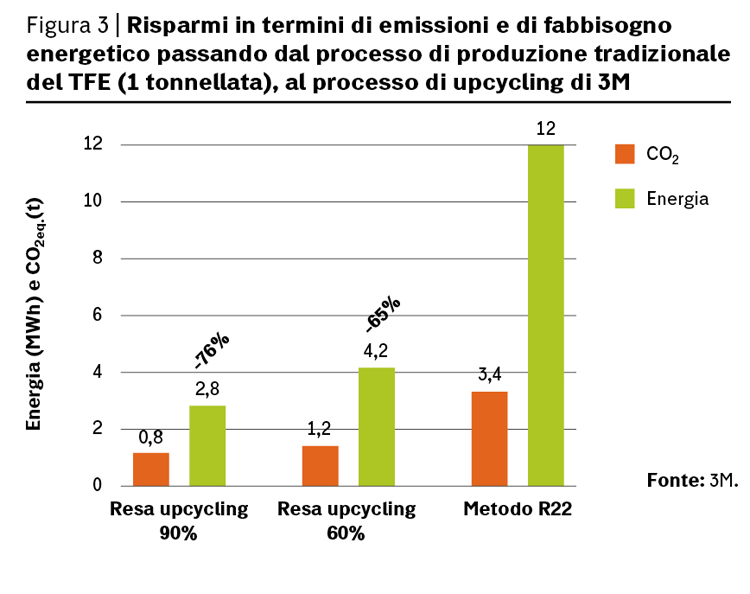

Closing the loop can be achieved also by another business model, upcycling. 3M is a good case in point. Its DyneonGmbh branch has open the first plant for the recycling of fully fluorinated polymers: PTFE present in waste is reduced to its original polymer and used to produce new PTFE, thus eliminating the need for new virgin raw material and avoiding the landfilling of EOL (End of Life) products containing this polymer. Replacing the traditional process with upcycling neutralizes the dependence on virgin raw materials, even critical ones, and reduces CO2eq. emissions and energy consumption up to 76%. Closing the loop means moving from a recycling model, that can cause a reduction in the quality and uses of a product, to an up-cycling model restoring the material to its initial and purer state, ready to be polymerized and re-introduced into the manufacturing process, with no use and performance limitations.

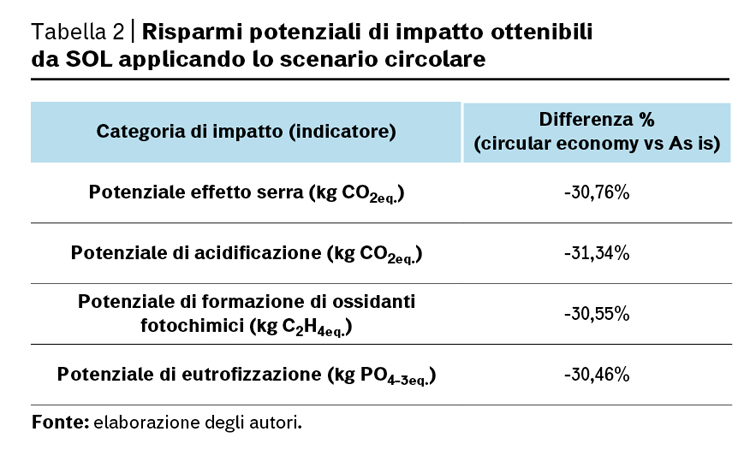

The last approach is durability, adopted in its trial by Vivisol, one the leading European groups operating in the field of home care, in particular with respiratory problems. Through an LCA study on the invasive mechanical ventilation kit, aimed at investigating the extension of the product’s durability to avoid value reduction, a comparison between the current scenario and a hypothetical circular economy scenario where unused components of the kit are returned and redistributed after safety and quality checks was carried out. According to the results, the winner is undoubtedly the circular scenario compared to the current one. By extending the life not only disposal and the ensuing replacement with a new product are delayed, but the value of the very products is perpetuated.

The CERCA project has offered a lot of food for thought and case studies have highlighted some important data on drivers, results, leverage and barriers.

The path followed by companies taking part in this project presents some common elements that have become the drivers of “circular” strategic choices. First, in all cases there has been an increase in process efficiency that in turn has become an important advantage, namely cost reduction. In the medium and long term, the payoff of this process of internal redesign and check-up translates also in a significant and lasting economic return capable of providing a stimulus for continuous improvement. The base of this return can be savings generated by cheaper supplies (upcycling and remanufacturing), more efficient processes (dematerialization) or extension of the life cycle and value exploitation (durability).

Moreover, the return is not just economic, but it also affects image and competitiveness: the first companies to get involved, thus anticipating the market, can enjoy an advantage, not only from a competiveness point of view compared to competing firms as first movers, but also from an image perspective with customers, users and consumers. This can include customer retention both in B2C relationships and above all in B2B, for instance in the cases of 3M (upcycling) and NitrolChimica (remanufacturing) that have established a virtuous circle of supplying with quality second raw materials to their customers who have also taken up the role of suppliers.

One of the main drivers is still legislative pressure, despite not having set binding or mandatory standards, both at national or international level. The same legislative pressure can turn into a twofold opportunity: on the one hand, preparing and anticipating future legal requirements, on the other hand raising awareness amongst institutions and stakeholders in general thus becoming a promoter of change.

Results achieved by companies offer plenty of food for thought, characterized by an important common factor: in every single case data clearly point to lower impacts leading to ensuing environmental benefits.

Two main elements stand out amongst the leverage factors promoting these paths. First, the network has proved to be of crucial support with multiple roles: optimizing logistic, initially a week link of business circularity that has turned into a strength (NitrolChimica); making durability feasible and real by using something that can still have great value (Vivisol); setting up a direct collection system of their own “exhausted” products (3M).

Second, recognized scientific tools, such as LCA (Life Cycle Assessment) and LCC (Life Cycle Costing) proved their validity in providing efficient and stimulating support in preliminary assessment of the potential efficiency of circularity in one’s business. Carrying out an environmental impact analysis can highlight unknown inefficiencies and impacts thus managing more effectively activities aimed at fully adopting the circular economy strategy.

Nevertheless, closing the loop and the redesigning process can inevitably run into obstacles.

First of all, the return linked to a positive image might not be obvious and consumers’ lack of knowledge and awareness can slow down innovation. Suitable countermeasures are needed, communicating innovation and reduced environmental impacts so that consumers can make rewarding purchasing choices. It goes without saying that communication must be effective and institutions must take up the role of raising awareness.

Moreover, in the current panorama, institutions must eliminate technical and legal-bureaucratic obstacles hindering the full transition towards a new circular model by reducing ongoing difficulties in reusing residues or waste from other productions by promoting better homogeneity in second raw materials considered input and output, thus supporting an active and competitive market and finally, by tackling the logistic management of waste primarily by rethinking and reformulating the concept of waste, first important step towards the elimination of current legislative barriers.

This last consideration can be seen as one of those elements causing difficulties in involving supply chains, in particular those different from one’s own with which to establish synergies to discover possibilities and opportunities deriving from the creation of industrial symbiosis. At the same time, it is not always simple and straightforward to actively involve B2B suppliers and customers to optimize the life cycle of a product to make it “circular.” This commitment must be shared by all the actors and their interest must go beyond the mere economic advantage/disadvantage in the short term.

And this leads us to our last point, inevitable scale and economic barriers that can slow down or prevent investments in innovation processes requiring a clear institutional stance promoting economic and/or tax incentives, or can become transition costs to activate the needed network or implementation costs to support the very innovation process.

Info