Structural funds are an intervention tool created and managed by the European Union, sever-year programmes so that member States can embark on smart, inclusive and sustainable growth where the sustainability principle will have to inspire across the board the actions of all countries funded. They are the biggest source of funding for both national and regional projects: they take up to 35% of EU’s total budget.

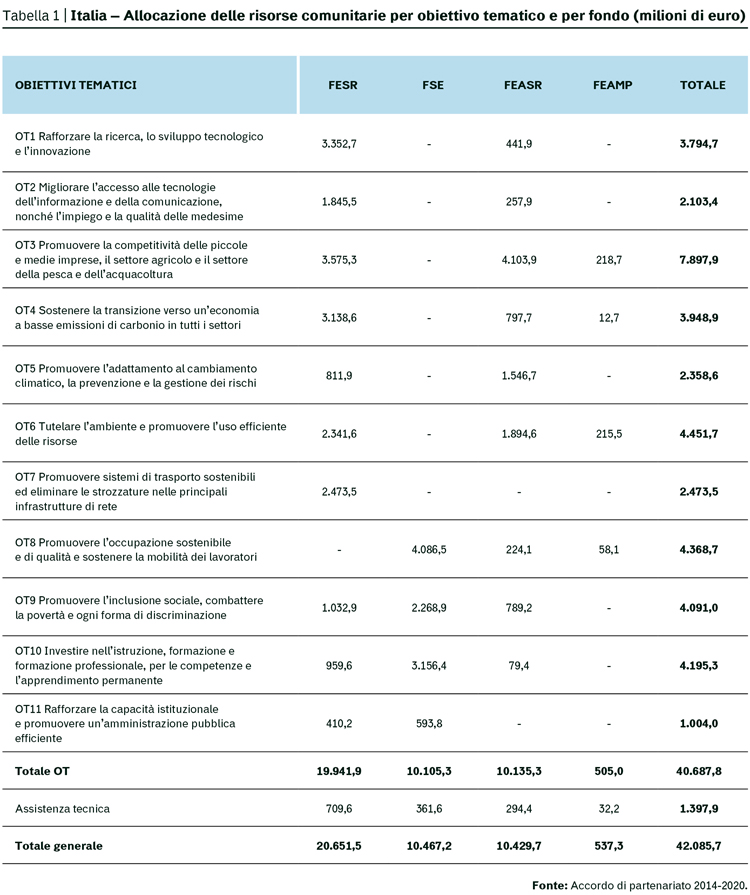

In Italy, the partnership agreement, adopted on 29th October 2014, represents a reference framework for the operational planning of EU resources between 2014 and 2020 through national and regional programmes (PON and POR respectively), and it is structured in 11 thematic targets. Each target attracts the allocation of financial resources relevant to one or more reference funds (see table 1).

In particular they can be divided into EFRD – European Fund for Regional Development (financing mainly production activity in the industrial and service sector), ESF – European Social Fund (people and training), EAFRD – European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (agriculture), and EMFF – European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (coastal areas, fishing).

Some targets pursue purely environmental aims (water and waste management, risk forecasting and adaptation to climate change, reclamation of polluted sites, production of renewable energy and energy saving, biodiversity), while others will only fund actions partly linked to the environment. This is the case of the transport sector where a share of the funds will be assigned to sustainability (rail/sea transportation) or to research and innovation envisaging the inclusion of actions supporting process of technological transfer and cooperation in companies based on low carbon-emission economy. Or education and training where there are clear references to environmental and sustainability themes.

Another opportunity that must not be undervalued for the promotion of the green economy is the sizeable investments included in the national programmes such as, for instance, “Enterprises and Competitiveness” and “Research and Innovation.”

In this complex planning, fund managing bodies (each region has identified one for each fund, at national level as well, a body has been appointed for each fund) will be asked to interface with the new procurement code that as we know envisages compulsoriness of green public procurement (GPP) for commissioning bodies. Environmental Minimum Requirements (EMR) issued by the Ministry of Environment thus become an important fundamental and reference document for procurements that will be envisaged by structural funds, but this will give rise to both opportunities and criticalities.

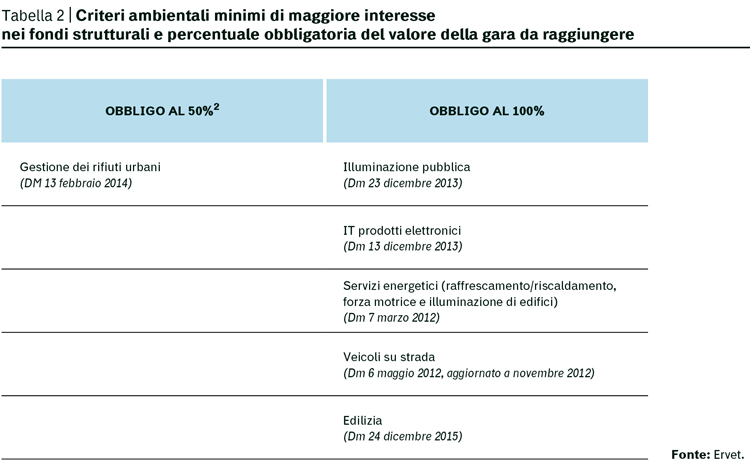

Surely, when structural funds finance directly projects of public bodies, the application of the new procurement code will entail the use of environmental minimum requirements for certain categories establishing thresholds that must be achieved in terms of total value of the bid. Table 2 presents EMRs that will be most used for analysing the typicality of costs allowed in structural funds.

The expectation is that all processes of public works awarding started by public bodies will be green; if EMRs are not applied, these processes might be appealed. Compared to the previous framework, this is a huge step forward since before compliance was on a voluntary basis and only percentages to be achieved at national and regional levels were established (50% for total contracts in the national action plan) and monitored through a system that never took off and that did not provided for any sanction for non-fulfilment.

This is a positive element that will guarantee a stronger application of EMRs and an increase of environmental sustainability in public procurements, but there are still some doubts.

First of all, it is clear that the application of EMRs cannot represent a real incentive towards “radical” environmental innovation. On the one hand, the contents of the very environmental requirements, it is not a chance that they are called “minimum,” despite stimulating low environmental impact products they do not go beyond the threshold of innovation already largely present on the market (even in virtue of the non-discrimination principle). On the other, they stem from the need to renew some criteria issued a long time ago and on the old procurement code and on laws preceding Collegato Ambientale (environmental law promoting green economy measures while reducing the excessive use of natural resources, translator’s note).

Another critical element is the lack of assessment tools of life cycle costing introduced by the new procurement code. Life cycle costing is difficult to carry out because there is not, not even at European level, a clear and realistic assessment method that can be used for different product categories as it emerged from real applications of EMRs in the transport sector. This lack implies a clear difficulty in defining a correct trade-off between economic and environmental costs.

Secondly, it is useful not to undervalue what has already emerged at general level, in other words that drastic cuts of public spending do not stimulate public bodies, and in general commissioning bodies, to invest in “advanced” green public procurements that could entail additional costs. As a matter of fact, although incurred expenses are not included in the Stability Pact when using European funds, it is feared that recipient bodies will use them to meet costs that they will not be able to afford with ordinary revenue.

These elements lead us to say that if we want GPP application to become a driving force for innovation and for achieving substantial environmental results in Italy, we must act quickly on structural funds in order to provide commissioning bodies (and managing authorities) simpler and revised tools and information.

Lastly, it is worth highlighting an element of structural funds synergically linked to GPP: that is the opportunity to finance pre-commercial procurements (PCP). Pre-commercial procurement is a call for tenders only for R&D services in order to buy a service or a product not present on the market, through a series of models of award of contracts. PCP envisages the sharing of risks and benefits between the commissioning body and enterprises, co-financing by participating enterprises, trial on a limited amount of new products and services. PCP takes care of procurements “dealing with R&D services differing from those whose results belong exclusively to the commissioning body so that it can use them while carrying out its activity, on condition that the service is completely paid for by such administration” and could be synergically linked to what the structural funds finance for targets 1 and 3 (research and competitiveness).

Accordo di partenariato 2014-2020, www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/it/AccordoPartenariato/

This article has been made possible thanks to Viscolube support