It is possible, through simple actions and small changes in our daily routines, to make a real difference in reducing the environmental impact of plastic. This same outcome, however, is much more difficult to achieve in certain sectors. The healthcare industry is an example of this problem, with single-use plastics constituting 85% of instruments used. This has been considered essential to ensure hygienic and sanitary standards required to guarantee safety and effectiveness.

It is possible, through simple actions and small changes in our daily routines, to make a real difference in reducing the environmental impact of plastic. This same outcome, however, is much more difficult to achieve in certain sectors. The healthcare industry is an example of this problem, with single-use plastics constituting 85% of instruments used. This has been considered essential to ensure hygienic and sanitary standards required to guarantee safety and effectiveness.

Plastic made its appearance in hospital wards in the 1970s, slowly replacing many existing instruments that were originally made of metal or glass, and which had to undergo expensive sterilisation procedures in order to be safe to use. The advent of plastic allowed for a series of benefits, including time optimisation for sanitary personnel, the reduction of costs and, most importantly, a reduction of the incidence of nosocomial infections. A truly revolutionary innovation, therefore, that greatly improved safety and working conditions in the healthcare industry, but with a big caveat: the lack of consideration for environmental consequences. Nowadays, in fact, a large majority of the plastic that enters a hospital doesn’t end up being recycled. This is because hospital waste is regulated by strict norms (such as the EU’s 2008/98/CE) which don’t allow for it to be mixed with any other refuse, given the high risk of contamination.

In fact, part of the plastic that gets sent to the incinerator could instead be recovered, as it is clean and recyclable. This has been demonstrated by a pilot study that began in Denmark in 2016. Research was conducted at Aarhus University Hospital, in collaboration with the Healthcare Plastics Recycling Council (HPRC), and here recycling was increased while new solutions for bolstering the circular economy were explored. To learn more about this we talked to Susanne Backer, Project Manager for Circular Economy at the Danish institution, which has 10,200 employees, a bed capacity of 1,150 and produces about 3,200 tonnes of waste every year.

How does the Aarhus University Hospital deal with its waste and what are your objectives going forward?

“In 2017, 16% of the waste produced by our hospital was recycled, while 83% was sent to be incinerated and 1% to landfill. Our objective is to recycle 50% of waste by 2024, thus reducing the amount sent to incinerators to 49%. In particular, we are trying to become more circular. The path we have to follow is very complex, because we need to develop a model with criteria that must be enforceable across the entire sector.”

|

|

The study shows that one of the wards that uses the most plastic is the operating room. Credit: Michael Harder |

What were the findings of your pilot study?

“We ran a small test by examining a 500 kg sample of solid waste. To do this, we asked healthcare operatives to separate plastic from all other types of waste and deposit it in separate containers. After this was put into practice, we were able to determine that 90kg were made up of clean packaging, originating from 162 different suppliers.

Subsequently, the collected plastic was analysed to determine the typology of its constitutive polymers. 500kg is undoubtedly a relatively small sample, but it still allowed us to determine that clean plastic packaging makes up 18% of solid waste. Therefore, it can be estimated that 300 tonnes – out of a total of 3,200 – are plastic packaging.”

What is the most common type of packaging?

“What emerged from our study is that the largest group of plastics is made up by sealed packets in which many sterilised instruments are delivered. This type of packaging is made of different polymers that make recycling more difficult. For this reason, it is critically important that we collaborate with both the procurement department and the suppliers, so that we can request specific recyclability requirements for candidates interested in making bids for procurement. Changes to plastic design – that make it more recyclable or, even better, reduce its use – will only be induced if hospitals alter their purchasing practices.”

How were you able to get suppliers involved in the project?

“The data collected from our analysis was uploaded to a database. After this, we compiled a list of the five most frequent suppliers. These were then invited – along with other representatives – to a meeting in which we presented our requests and objectives. We asked them to take part in a pilot scheme with the goal of finding better solutions. Together, we analysed one of the most simple items of packaging present in hospitals: bottles containing solutions for physical hydration (e.g. saline or glucose solution). Recycling these bottles presents a number of challenges: first of all, they would have to be made of a single polymer – ideally polypropylene (PP) – and the plastic used would have to be virgin. Most of these bottles, however, are made of multiple polymers and also have a label glued on, as well as a rubber membrane acting as a lid. All of this makes recycling more difficult.

Our analysis followed the guidelines set out by Plastic Recyclers Europe, a body that was founded in 1996 to promote plastic recycling in the European Union. We also adapted these criteria (see box) into minimum entry requirements to participate in a recent invitation to tender for the supply of bottles for hydration solutions to all Danish hospitals. None of the participants achieved the minimum required recyclability score of 50%, which only constituted 5% of the overall evaluation. Nonetheless, because the competition was so fierce, the points gained in the recyclability category were crucial in determining the choice of supplier.”

|

|

A AUH nurse as she puts on sterile gloves contained in double layer packaging, the most common type of plastic analysed. Credit: Michael Harder |

What are the best strategies for reducing packaging?

“The most efficient method is to reduce weight and volume: it would unquestionably save on costs and resources. Cutting down on packaging also reduces the workload of hospital staff, freeing up precious time that can be spent with patients.

A second strategy consists of using recyclable plastics wherever possible, such as in the second and third layers of plastic packaging (the first layer needs to be new plastic in order for the high safety standards to be met, editor’s note).

The final possibility is recycling. If something can’t be reduced or reused, it may be recycled, but to make this possible we have to establish criteria for procurement. The recyclable polymers are PE, PET and PP, and it is essential that our suppliers mark the plastic with the international recycling symbol, as well as reducing the use of mixed materials as much as possible. Even the combination of paper and plastic makes things a lot more complicated. Unfortunately, we are still at the beginning. We need time, at least ten years.”

A Pilot Scheme: Infusion Bottles

On the basis of the Plastics Recyclers Europe guidelines, Aarhus University Hospital has defined some minimal necessary requirements to take part in invitations to tender for the supply of bottles for physical hydration to all Danish hospitals.

The bottles must have clear markings indicating how to recycle the constitutive polymers, by using the 7 international recycling symbols. The preferred markings are ones conforming to Recommendation CEN WI 261 070, but ones that follow the European Commission’s 97/129/CE decision are also deemed acceptable.

95% of the total product must be made of a single constitutive polymer.

The lid must be made of HDPE, LDPE or PP. Any coating, seal or valve must be made of HDPE, LDPE, PP or PE+EVA.

The tamper ring must be made of PP, PE, EPS or OPP and have a density of less than 1 g/cm3.

The label must be made of PP, HDPE or LDPE. The glue must be soluble in water at less than 80OC. The label must be laser-printed with non-toxic ink, following EUPIA guidelines.

What difficulties have you been encountering?

“The problem with medical plastic is that the finished products have to be made according to specific procedures, and adhere to very high standards. This means that at least three years are needed in order for any design change to be approved. Time and constant dialogue are necessary to achieve results. Furthermore, suppliers of medical and sanitary products distribute on a global scale: this means that the changes they make must be relevant to the entire global market.”

How have waste collection companies responded?

“We have also been collaborating with waste management companies, and devoted time to ensuring they understand that the plastics coming from hospitals are safe. Otherwise, it is often the case that these companies are wary of hospital waste because they believe that it contains contaminated items.”

Do you have any contact with hospitals in other European countries?

“We have been communicating with some clinics across northern Europe, in Norway, Finland, Sweden, the UK, the Netherlands and Belgium. Unfortunately, we have yet to expand our reach to other European nations.”

Aarhus University Hospital, www.en.auh.dk

Plastics Recyclers Europe, www.plasticsrecyclers.eu

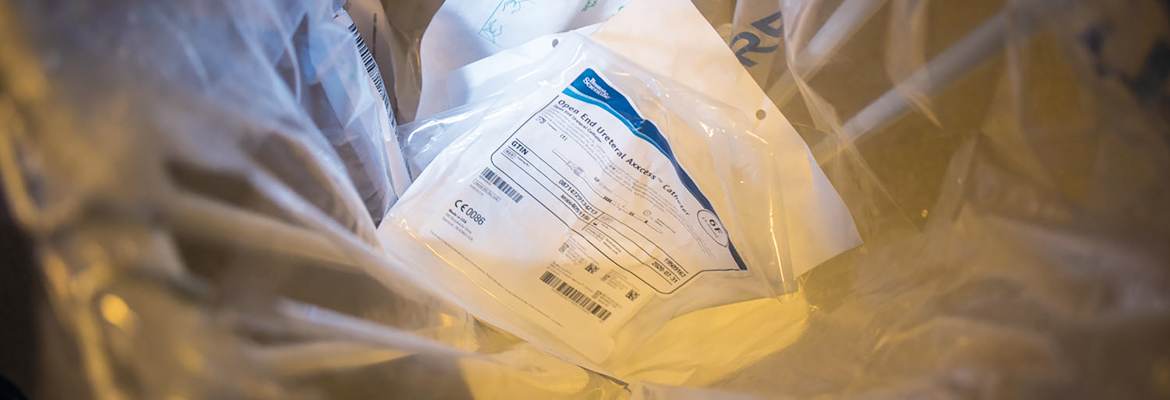

Top image: Hospitals all around the world have to deal with the problem of recycling their plastics. Whether these are single use, double-layer or complex plastics most end up in the general waste category and are not recycled. Credit: Michael Harder