Virtually, the aluminium of the beer can you had last night is everlasting, even if its use is a very recent application. Aluminium is not found in nature, for centuries its value rivalled that of gold. Only at the end of the 19th century, its extraction became sufficiently cheap to start its commercial use. Once extracted, aluminium can be used for a plethora of applications. A “permanent” material – like glass and steel – that is not consumed and can be used and reused endlessly.

“The Italian aluminium industry,” explains Cesare Maffei, chair of CiAl (Italian Consortium for the Recovery and Recycling of Aluminium Packaging), uses material derived quite exclusively from recycling. Aluminium is increasingly seen as a permanent material, nearly unbeatable when it comes to performance and industrial, environmental and energy costs. In our case, the closed loop approach, or endless recovery, enables us to keep chemical-physical performance unchanged and to recover it with every recycle. What other material can boast such characteristic? Surely not materials derived from fossil sources.”

|

|

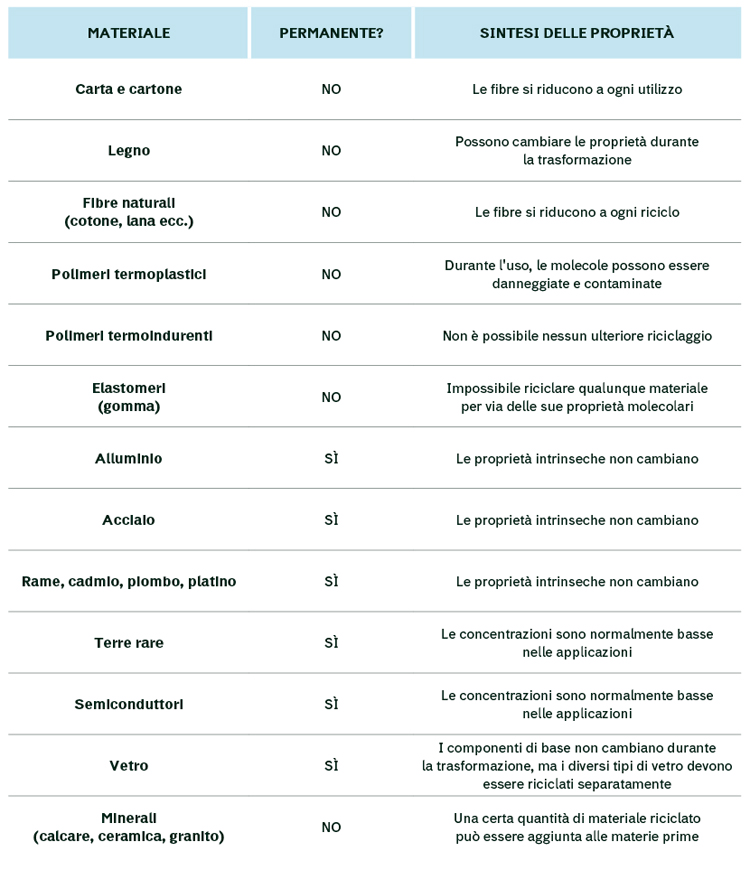

Source: “Permanent Materials – Final report,” Carbotech, 2015.

|

Aluminium cycle starts with bauxite extraction, a normally red mineral that got its name from Les Baux-de-Provence, a French area where in 1822 the it was mined for the first time. Despite being one of the most abundant substances on our planet, aluminium is not available in its pure form and must be extracted from rocks. A simple process but requiring industrial technologies and, on a global scale, a considerable amount of energy. An aspect that, unless we resort to renewable sources, requires fossil fuels. This is what went on for nearly a century and a half at global level: decades in which aluminium, in energy terms, had very high costs no longer sustainable today. And not only in economic terms, but above all from an environmental point of view because, due to energy production, millions and millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases were emitted into the atmosphere. For instance, it is estimated that at European level, the current recovery and recycling of 28 billion aluminium cans used every year offers a saving, in terms of greenhouse gas, of 3.2 million tonnes, equivalent to the emissions generated by cities such as Bilbao, Cardiff or Nice. This is because the recycling of aluminium offers an energy saving amounting to 95%. The remaining 5% is what is needed to manufacture aluminium products from aluminium already in existence.

In other words, this tantamount to saying that aluminium extracted over the last century is nearly enough for all our uses and needs. And since aluminium does not deteriorate, we have enough aluminium for times to come and we could no longer need bauxite mines.

To this end, “European Parliament resolution of 24th May 2012 on Europe’s efficient use of resources” – overcoming the distinction between renewable and non-renewable resources, including durable or permanent materials – becomes particularly significant. Letter G of this resolution calls for a conceptual revolution: “Whereas a future holistic resource policy should no longer merely distinguish between ‘renewable’ and ‘non-renewable’ resources, but should also extend to permanent materials.”

What does it mean in practice? That these resources are not consumed. Once introduced into the cycle, the same resource can be reused many times, because this is its intrinsic nature. While for instance, oil is burnt or chemically transformed to produce energy or plastic materials and it cannot return to its original state, aluminium can. And this is one of the reasons why today the concept of “permanent material” is spreading, a material that cannot be consumed and can be reused ad infinitum, conserving, in all its numerous applications, the necessary energy for future and new uses.

The assessments on which the European Parliament resolution is based, explains CiAl, derive from some considerations put forward by metal packaging European representative systems. In particular, they state that when considering the sustainability of different types of packaging, we must be clear about the link between natural resources used to produce materials that are then transformed into each packaging item.

Indeed, a very important point must be taken into consideration. We often say that natural resources are dwindling. Technically this is true. Aluminium itself, despite representing 8% of all matter present on the planet, is not infinite. “Normally,” explains Gino Schiona, the Director General of CiAl, “we do not take into account that materials such as aluminium and iron are elements and therefore they cannot be destroyed. Earth has not undergone any loss of metallic elements: they have simply been displaced and appear under different forms. Aluminium and steel are materials that can be transformed into packaging and use in many other applications, for instance in the construction, car, aerospace sectors. At the end of their lifecycle, used aluminium or steel, can be recycled and reused for other products. This creates a virtuous cycle.”

This enables us to fully understand why the definition of permanent material has not only a linguistic but also an economic value in the European debate on the circular economy. It is a further classification of a good that is not regenerated like renewable resources, but neither can it be consumed like non-renewable resources. And it is perfectly integrated into the concept of the circular economy.

Italy in Numbers

According to data from CiAl’s last annual report, in 2014 in Italy the total production capacity of secondary aluminium amounted to 808,000 tonnes, an estimated turnover of €1.87 billion with 1,600 workers. These numbers make the Italian market important at European level from an economic, strategic and employment point of view. Over the last few years, at least since 2010, Italy has regularly overtaken Germany, another big European producer of secondary aluminium. The estimate for 2015 amounts to over 710,000 tonnes, a number that amply exceeds Germany’s 605,000 tonnes. At global level, Italy and Germany rank third and fourth respectively behind the USA and Japan.

Aluminium recycling offers a 95% energy saving. And this datum does not change whether we are talking at global, European or national level. This is the energy gap between the production of aluminium packaging from virgin metal and packaging from recycled aluminium. This is no small difference, neither in terms of energy nor in terms of economic cost e above all the environmental impact due to gas emissions.

Thus, recovery activity becomes crucial. For instance, in 2015, CiAl-managed recovery, together with the activities indirectly managed through “recycled aluminium” smelting works companies and export flows, guaranteed a total recovery of 75.5%, recycling 69.9% of aluminium that entered the market. More than 90% is aluminium for the food industry, with a 4.9% increase of packaging items compared to the previous year.

In 2015, recycling 46,500 tonnes of aluminium packaging prevented greenhouse gas emissions amounting to 345.000 tonnes of CO2eq and offered and energy saving of 148,000 TOE (Tonnes of Oil Equivalent).

In its second life, aluminium has no problem in finding an adequate use. Italy’s data are very similar to European ones, with uses in different sectors, in particular in the production of durable goods. 55% in the transport industry, 19% in mechanics and electromechanics and 26% in the construction and household sector.

CiAl is currently committed in several projects aimed at highlighting the main characteristic governing post-consumer packaging management and aluminium in general: the metal-to-metal loop scheme and the concept of permanent metal. The principles of the circular economy are indeed intertwined with those of aluminium. The fundamental law of Antoine Lavoisier, the French chemist who lived in the second half of the 18th century, postulating that “nothing is created, nothing is destroyed, everything is transformed” is absolutely true for permanent materials and particularly for metals which, once extracted, can be reused ad infinitum. Aluminium is a good example.

And this aspect, as far as the need to reduce waste production is concerned, becomes extremely important. In his speech at the States General of the Green Economy 2016 at Ecomondo, Gino Schiona was very clear: “In packaging, a more intensive use of permanent materials could contribute significantly to preventing waste production. Aluminium in particular has shown for quite some time the highest prevention performance: for each type of packaging, the quantity of material used equals that needed to guarantee the required features. From a few microns (a tenth of a hair) of an aluminium sheet to make drink packs to thicker materials such those used in cans and aerosols. It is clear that aluminium means ‘prevention’ if we take into consideration its complete and endless recyclability. Moreover, aluminium packaging, thanks to its capacity to protect food, drinks and other products from light, air and microorganisms, has the most efficient barrier effect currently available on the market of materials. From design to its use in construction and transport, this metal helps make a product durable, giving it its characteristic of permanent material, overcoming built-in obsolescence and the disposable logic.”

Info