Until recently, the very effects of climate change could be described with tables and scientific papers, but at the same time it was hard to offer a clear picture. How can a century-long global phenomenon be explained? The colossal work by Fabiano Ventura, “On the Trail of the Glaciers,” analyses historical photos of mountain glaciers taken in the Karakoram, the Caucasus, Alaska, the Andes, the Himalayas and the Alps. It compares these with pictures of the same places as they are today using the same vantage point (repeat photography).

Comparison and the visual power of images reveal the dramatic transformation of glaciers due to climate change. In Spring 2018, Fabio Ventura completed his Himalaya expedition together with geologist Andrea Bollati and documentary director Federico Santini. The team – led by a large group of Sherpas – explored the section of the Himalayan range bordering with Nepal, India and China; comparing the current state of glaciers with photos taken in the past during some of the greatest expeditions on Mount Everest and Kangchenjunga, two of the three highest mountains in the world. The historical photos used (some of which you can see on these very pages) are those of the 1899 expedition by English mountaineer Douglas W. Freshfield, which also included Italian photographer Vittorio Stella, and those taken in the 1920s and 1930s in expeditions that included George Mallory and Edward Oliver Wheeler, two of the first Britons to lay their eyes on Mount Everest.

“We use image comparison as a tool combing the communication power of pictures and the rigour of historical and scientific research,” explains Fabiano Ventura. “Images witnessing the shrinking of the biggest mountain glaciers in the world together with scientific data collected, provide an immediate picture of the extraordinary climate change that our planet is experiencing and confirm the urgency of all possible actions to contain its consequences.”

“On the trail of glaciers,\" sulletraccedeighiacciai.com

In 2020 the final stop of the project will take place: “Alps 2020.”

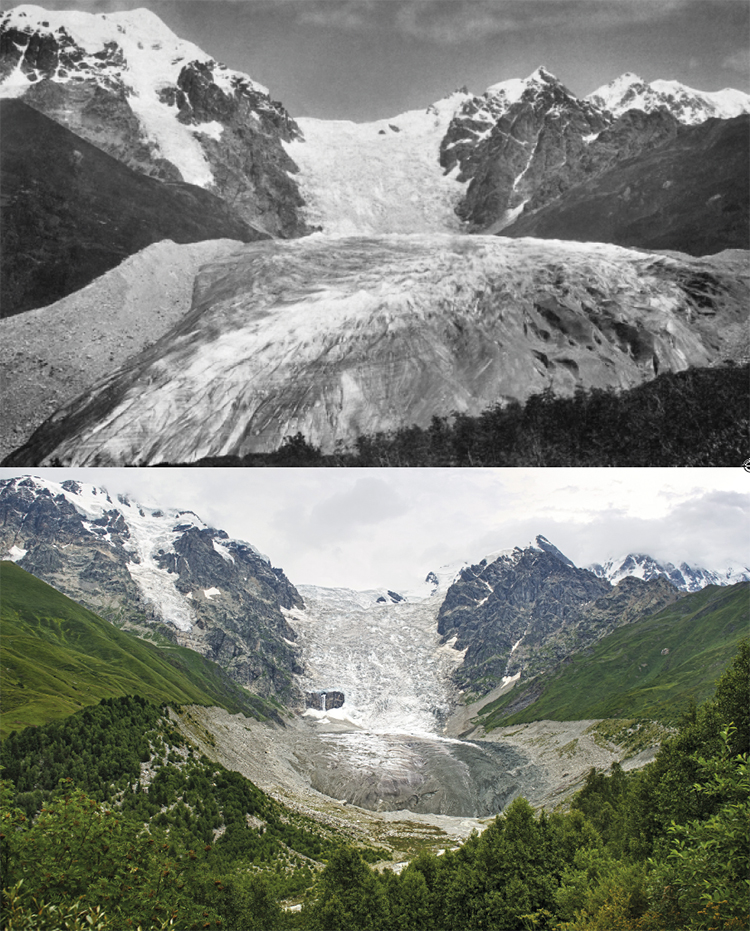

Caucasus

The Adishi glacier in Suanezia

To the right, a frontal view of the Adishi glacier, situated in the central part of the Great Caucasus mountain range in the region of Svaneti, Georgia. From a comparison of the images it is quite clear that there has been a collapse of the entire frontal surface area of the glacier. The length of the Adishi glacier is of 9 kilometres and its surface area spans over 12.9 kilometres squared. The glacier’s tongue stops at 2,298 metres above sea level, with a drop of over 1,000 metres, making it one of the most spectacular glaciers in the region. The Adishi glacier, that takes its name from the nearby village, is the source of the river Adishichala, an important water basin for the region.

Top: Mor von Dechy, 1884 – ©Royal Geographical Society

Bottom: Fabiano Ventura, 2011 – ©Archivio F. Ventura

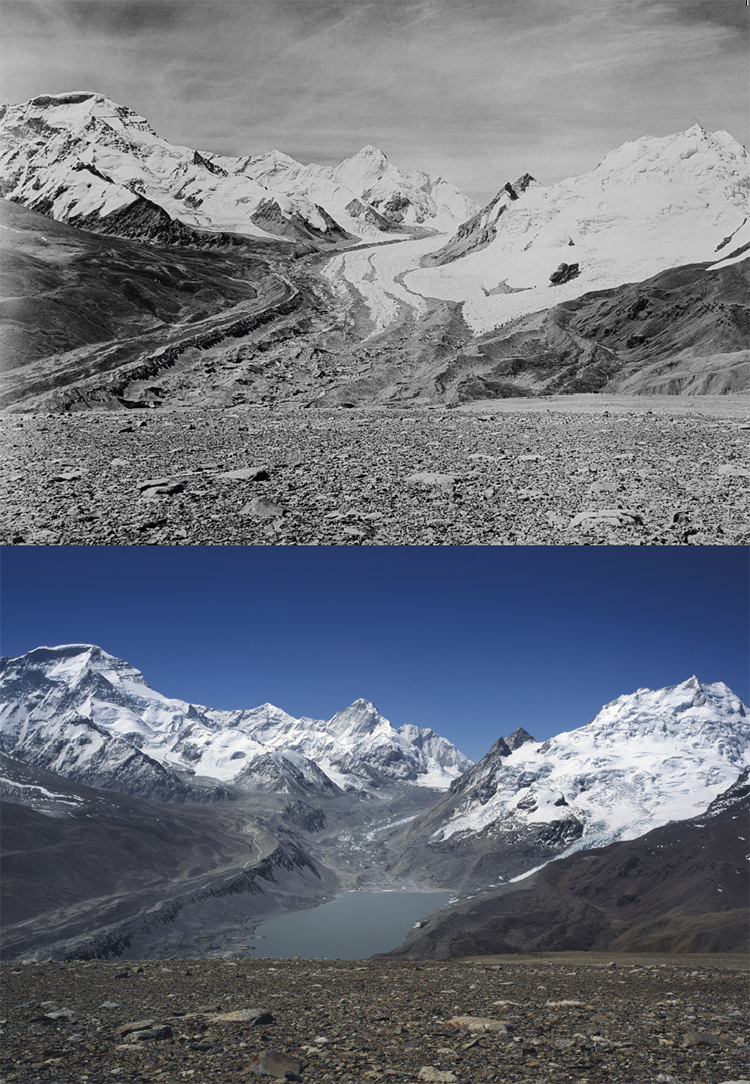

Himalayas

Gyarag Glacier

The Gyarag glacier and Mount Cho Oyu (8,201 m), the planet’s sixth highest mountain. Thanks to the photo’s perspective, which has been taken from a particularly high angle, the comparison highlights the impressive glacial lake that has formed over the last 50 years following the melt of the glacial surface that today spans over 2 kilometres long and 600 metres wide. Unfortunately, the formation of these lakes is now a common characteristic of Himalayan glaciers, often representing a danger to the valley populations. In fact, flash floods have occurred following the rupture of natural dams that hold back the water.

Top: Major E.O. Wheeler, 1921 ©Royal Geographical Society

Bottom: Fabiano Ventura, 2018 – ©Archivio F. Ventura

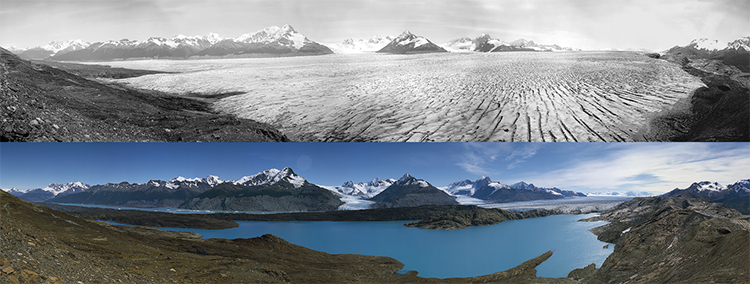

Andes

Upsala Glacierand the frontier between Chile and Argentina

85 years later the Upsala glacier in the Parque Nacional de los Glaciares in Argentina, has retreated over 15 kilometres. The valley pictured in the photo is 90 kilometres long and over 10 kilometres wide.

Its name derives from the Swedish university Uppsala (taking the old spelling, Upsala), that conducted the region’s first glacial studies during the 20th century. The northern part, that works its way down from the ice field, is found in the non-concluded boundary section of the contested Southern Patagonian Ice Field between Argentina and Chile, both of whom continue to place the ice in their official maps.

Top: Alberto Maria De Agostini, 1931 ©Museo Borgatello

Bottom: Fabiano Ventura, 2016 – ©Archivio F. Ventura

Alaska

The point of conjunction between the Muir glacier and its tributary Riggs in the Muir fjord

The image was taken from photographic point number 4, the White Ridge, in the current Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. 72 years later, the terminal part of the Muir glacier in the Glacier Bay National Park has retreated almost 20 kilometres, almost disappearing from the photo. The photographic comparison documents the significant changes in landscape, such as the growth of thick vegetation on the mountains surrounding the Muir fjord, in a very clear way. Furthermore, notice the relationship between the trimline of the mountain in the background and the height of the glacier in the historic photograph, which in the central area was over 700 metres thick.

Top: William Osgood Field, 1941 ©Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks

Bottom: Fabiano Ventura, 2013 – ©Archivio F. Ventura