Collection of the organic fraction continues to grow in Italy. This gives us a profile of excellence compared to the rest of Europe, and in some cases such as Milan, even compared to the rest of the world. However, more could be done. Much waste is still not transformed into compost or biogas: the circle that the principles and the related advantages of a circular economy require is not completed. Why?

This is due to political delays but also to obstacles put in place by committees who do not want yet another plant on their territory. Now that the European Union seems to have found the right path – after the faux pas of the Junker Commission in recent months – and Italy has provided a new incentive to the market of organic waste through the “Sblocca Italia”, change is looking more likely.

In order to understand the the bigger picture, we need to go back to the numbers of this incredible growth of organic collection in Italy.

In the last decade, the average annual increase has been of about 10%: today, organic waste is the main component of all urban waste collected in Italy. According to the most recent data by CIC, the Italian Composting and Biogas Association, in 2013 it reached 42% of the total, compared to 37% in the previous year. In practice, these percentages amount to 5.2 million tons of organic waste (wet and green) out of a total of 12.5 million tons of differentiated urban waste (of this, 3 million tons are made up of paper and 1.6 of glass).

This is an important result not only in quantitative terms but also as a model to export. “If we look at the European data on ‘biowaste’ – explains Massimo Centemero, Director of CIC – we are in third or fourth place. However, this is a distorted picture, as it is necessary to disaggregate the different flows of green and wet. In Germany, for example, the collection is done door-to-door and considers the two fractions as one. The German wet fraction is indeed very little, while in Italy we have separated the flows, one is for the green and one for the wet fraction.”

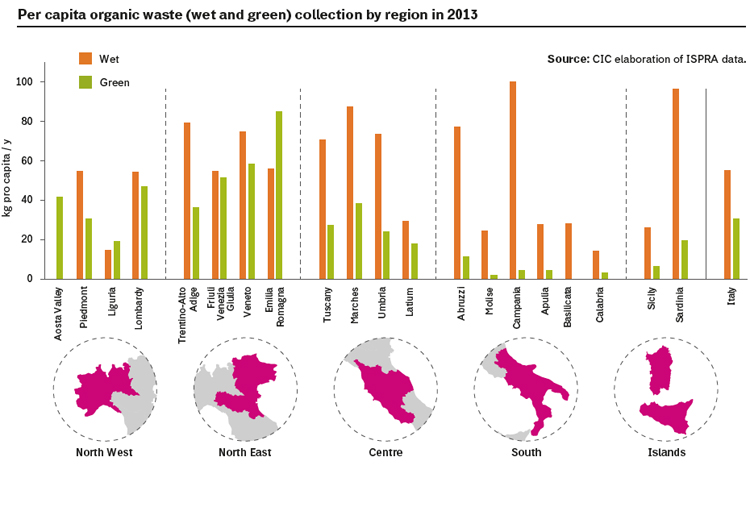

“Another example? Let’s analyze the dry fraction” Centemero continues. “In the Italian dry fraction we have an organic residue inferior to 15%, in Germany this percentage is 30%. Italian per capita collection reaches 80 to 100 kilograms a year in this section, much higher than the German one.”

The national average data for per capita organic waste is 86 kilograms, with highs of 108 kilograms in the North, and levels of 77 in the Centre and 62 in the South. However, the general picture in the South is not at all negative: if we consider only the population effectively served by recycling systems, the average values of recovered organic waste amount to 110-130 kilograms per person.

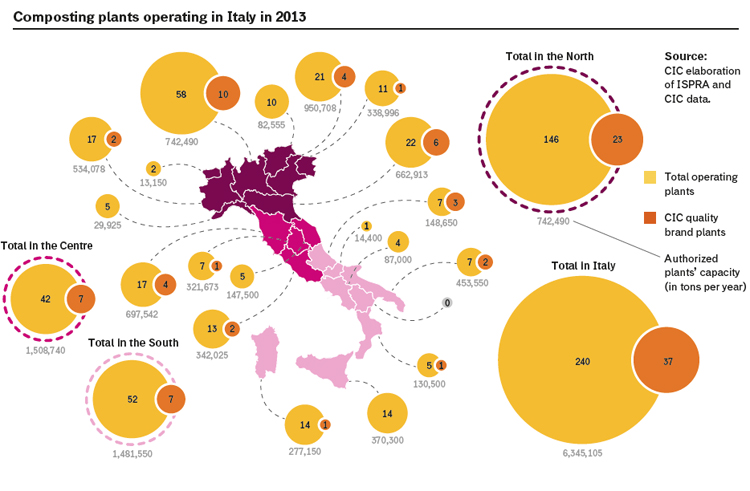

Does this mean then that all Italians are virtuous? There are certainly differences but they relate more to the plants than to the citizens’ response. Let’s analyze the trend of the composting plants: “Growth in organic waste recycling is closely linked to the development of recovery plants” states the latest CIC report presented last November. “In the space of 20 years (the first organic waste collection systems date back to 1993) an industrial system dedicated to the transformation of organic waste has been developed and consolidated. In 2013, this system comprises of 240 composting plants, 130 of them being industrially significant. The number of anaerobic digestion plants also continues to increase. In the three-year period 2011/2013 it grew by 60% with a total of 43 operational plants.”

“Today we have about 4.6 million tons of treated wet fraction but we could easily get to six or seven million in a short time. If the institutions really applied sanctions we could reach this objective in one year. We need more plants, especially in the South, but not only there. All regions have new plants in the pipeline, but how many are still on paper?”

In numerical terms, we read in the report that analyzes the ISPRA data, 61% of plants are located in the regions of Northern Italy, which started recycling the organic fraction of urban waste long ago, while the remaining plants are equally distributed in the Centre (18%) and the South (21%). The operational capacity is distributed as follows: 23% of authorized amounts of waste are in the South, 24% in the Centre and the remaining 53% in the North.

Closing the circle: vehicles fuelled with biomethane derived from “wet fraction”

Technology and necessity have made recovering biogas from organic waste possible and opportune.

If wet fraction collection was widespread over the whole territory, explains the CIC report, we could obtain about 8-9 million tons of kitchen waste. If these residues were then transformed into biogas we would be able to obtain over 450 million cubic metres.

In addition to the future possibility of accessing incentives, today, if all the wet fraction of recycling were to be transformed into biomethane through anaerobic digestion plants, we could fuel 80% of the vehicles used for waste collection. In those parts of Italy where organic collection is or could be particularly high, such as Campania and Sardinia, we could even fuel 100% of the vehicles.

The model envisaged by Centemero and CIC is a mixed partnership where the publicly owned plants are then managed by a private company. “There are cities like Rome – states the Director of CIC – where at least two plants with a capacity of 100-150,000 tons have been needed for a long time, but nothing is happening.” Obviously something went wrong. But what? “In Italy we have had proper technologies and examples of excellence for over 20 years. We only need to look at them and use them as models. Politics is certainly a problem, as well as the many appeals by local committees.”

To have an idea of what Italy is losing by waiting for a more efficient policy, let’s analyze the data gathered by the Observatory Costs of Not Doing, a body integrated by Trenitalia, ACEA, ENEL, Gruppo Hera, Assolombarda, FederUtility and Terna. According to the observatory, if composting infrastructures are not built, this would cost collectively about 3.3 billion euros for the period 2009-2014. Article 35 of the “Sblocca Italia” could be an important turning point. While the first clause relates to incinerators – a very divisive issue – the second clause specifically deals with the organic fraction of urban waste, following the direction that CIC was wishing for.

|

|

ETRA biotreatment plant in Camposampiero, Padua |

But what is happening at the European level? Will Italy be able to demonstrate that its model is a winner, especially after the Juncker Commission put a halt on the package in favour of a circular economy?

This is a valid question because – after provisions were presented to restructure the whole waste sector so as to drastically reduce landfills, bring the amount of recycling/reuse to 70% and cut by a third the production of food waste in the next ten years – the Commission has practically stopped all the work that had been done. The package also included 100,000 jobs which Europe desperately needed. This drastic and unpredicted change of direction by the Juncker Commission has come as a wet blanket, generating mobilization by the organizations active on environmental issues, including the ECN – the European Compost Network – of which CIC is a member.

“Since then the situation has improved”, explains Centemero. “Junker’s stoppage turned out to be purely strategic, probably dictated by the fact that those were very complex and binding regulations, therefore difficult to become effective in many countries. We were reassured that the Commission wants to proceed towards the circular economy, however it is necessary to give the member States time to adjust”.

Last March the Commissioner for the Environment Karmenu Vella publicly declared that “the Commission has decided to reflect carefully on how to reach the objective of a circular economy in the most efficient way and in total compatibility with the political agenda on employment and growth. A constant improvement in waste management remains a priority to be achieved through policies of incentives and support to waste reduction, separation and high quality collection. We will maintain recycling policies according to the EU objectives”.

As further evidence that the Commission is really committed to these objectives, at the beginning of February it wrote to the European Compost Network: “The Commission – the letter states – is fully aware of the importance of the environmental and economic challenges linked to the circular economy and will deal with this matter in the most ambitious and efficient way”.

The letter was signed by Karl Falkenberg, Director General of the DG Environment of the EU Commission, the same Karl Falkenberg who recently admitted how amazed he was with what had been achieved in Italy and Milan in particular, which in 2013 even surpassed San Francisco in terms of collection of the organic fraction. This is another proof that the Italian model is a winner and therefore, should be exported.

Milan: ranking first worldwide

The case of Milan has even surprised the Director General of the DG Environment of the EU Commission. In Milan, between 2012 and 2013, separate collection of the organic fraction has been extended to all the city’s households.

Since June 2013, 1.3 million people regularly separate kitchen waste. As a consequence, Milan has achieved the world record as the city with the highest number of residents served by wet fraction collection, even surpassing San Francisco with its 830,000 inhabitants.

In Milan, the collection system gathers about 90 chilograms of annual per capita collected waste, managing to recover almost 120,000 tons a year. According to CIC analyses, the average quality of the organic fraction is roughly 4-5% impure.