Turning the “wolves of Wall Street” – oblivious to any good cause – into lambs at the “planet’s sickbed:” a strenuous, nearly contrived, undertaking. And yet there is nothing that attracts investors quite like money. Especially where industrial and energy policies of various countries decidedly point to moving away from fossil fuels and raw material-devouring production systems in favour of clean energies and models based on circular economy’s principles.

The latest confirmation came from the conclusions of the One Planet Summit, a world’s rendez vous on the environment attended by 50 heads of State and Prime Ministers, held in December in Paris. Part of it was a showcase promoted by French Emmanuel Macron to strengthen the image of France as a climate champion and also an opportunity to reiterate a concept that, at least on paper, should be almost self-evident: no revolution (much less a green one) can be started without money. Many French analysts noted that bankers and financiers, rather than politicians, have been the most affected by the speech given by Macron and Nicolas Hulot, his Minister for the Environment. On the other hand, France, with its sixty nuclear plants to be decommissioned or to be remodelled at a huge cost, can become the ideal territory for those prepared to grant a loan to energy magnates committed to transitioning from atoms to renewables.

EDF (Elecriticité de France) approved the issuance of a mega-green €25 billion bond to fund its 30 gigawatt “Plan Solaire” and 30,000 hectares of PVT fields.

What happens in the energy world is not that different from what occurs in other industrial sectors concentrated on finding a way to reduce the use of natural resources, to rethink production systems, to develop reuse and recycle systems. Many actions combined in the principles of the circular economy that can bring about vast effects, providing there are adequate resources able to fund the transition.

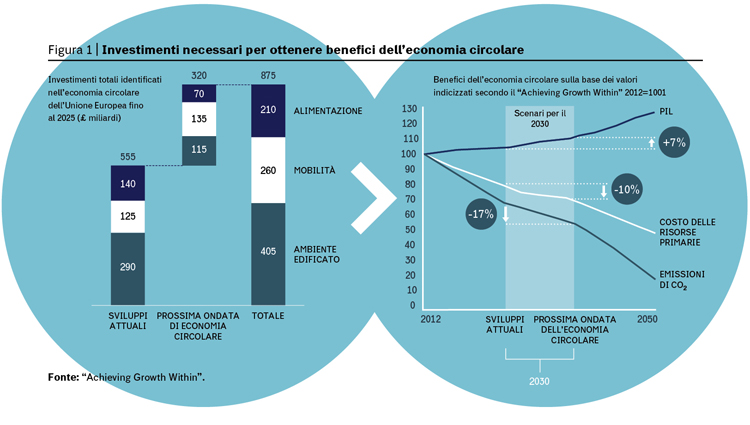

Exactly one year ago, a report presented at the 2017 World Economic Forum by Systemiq, a venture capital company, together with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (“Growth within: a circular economy vision for a competitive Europe”) determined that €320 billion fund were necessary to change the development model from then until 2025. By supporting with the appropriate resources the changes in mobility, food and the construction sector (the three macro-areas explored in the report) because they were responsible for 60% of the expenditure of European households and 80% of the use of resources, the European Union would increase its annual GDP by 7%, while reducing the use of raw materials and CO2 by 10% and 17% respectively.

Finding funds for the transition is a primary necessity for the Old Continent, given that between 1900 and 2009, industrialization led to a tenfold increase in the use of raw materials and national energy use has soared seven times. Moreover, EU is the first resource importer (€760 billion a year, 50% more than the US). 60% of fossil fuels and metals come from non-EU Countries. And 40-60% of costs incurred by continental manufacturers are imported: a clear disadvantage for their global competitiveness, linked to price volatility and reliance from abroad (20 raw materials have already been deemed as critical by the European Union in relation to the risk of getting them).

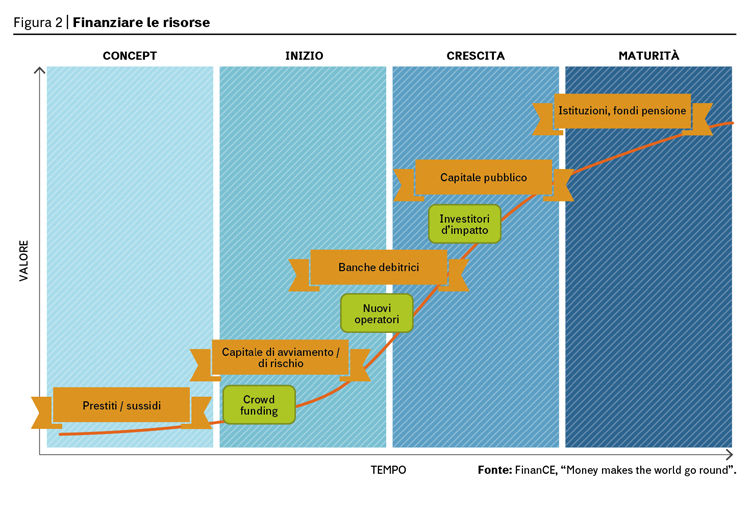

True, but who should we turn to when it comes to financiers? It actually depends on the type of business to finance. “There are many different kinds of financial products necessary to fully exploit circular business models” as explained in the report “Money makes the world go round” drawn up by the work group FinanCE, joined by banks (including Intesa San Paolo), universities and European institutions (EIB and EBRD). “For instance, in the transition phase where a business moves from a linear to a circular business model, the risk profile may be more suited for higher risk capital, through an injection of equity or internal capital. Once the transition is complete, a move to lower risk capital, through specialist asset lending and generic debt facilities may be more appropriate.”

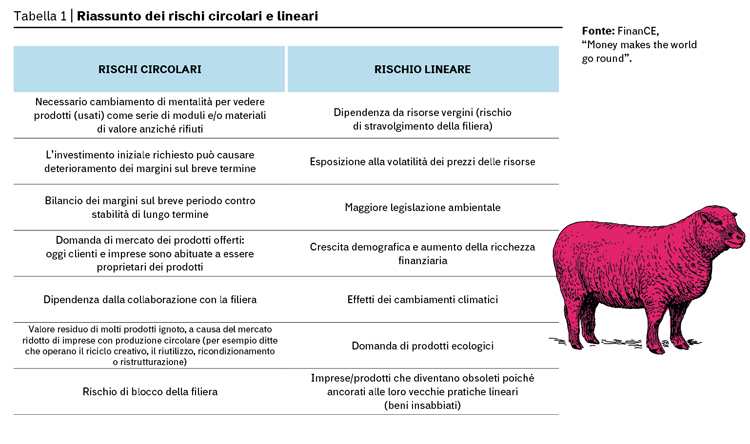

The core is always the risk profile of any given company or entity, which can be suited for some forms of funding but not for others and is often connected to business maturity (see figure 2). “The level of risk will be reflected in a risk premium” highlight FinanCE’s analysts. “When it is high, the prize must be high, because the financier must be rewarded for the risk taken.” Actually, even the circular production world has its own unknowns that every potential investor invariably assesses (see table 1). Nevertheless, it is precisely the increasingly obvious risks of the linear approach to make funds for transition “une bonne affaire” as written on the front page of Le Figaro during the days of the Paris summit: reliance on raw materials, exposure to price volatility, effects of climate change, increasingly restrictive environmental laws and augmented awareness of consumers towards low impact products.

Thus, the proliferation of stances in favour of clean energies and circular economy situations by small and large investors is no coincidence. Starting from a number of Europe and world pension funds, which are disinvesting hundreds of billions of dollars (the Norway’s sovereign fund alone announced 35 in November), worried that investments in fossils and other examples of the old linear economy turn into stranded assets, which translate into losses for savers and shareholders.

There is some movement also at Community level, where the EU’s Commission in May created, together with the European Investment Bank, a platform for financial back up to the circular economy, bringing together national banks, institutional investors, the European Fund for Strategic Investments and InnovFin initiative within the 2020 Horizon programme. A way to close the gap created by poor specific funds for the circular economy which, for the two-year period just gone, reached a mere €650 million.

“As world’s leading financier of the multilateral climatic action – with over €19 billion of funds last year alone – we deem the circular economy a key factor to reverse the climate change course, and we intend to use in a more sustainable manner the dwindling resources of our planet, thus contributing to Europe’s growth” explained Jonathan Taylor, EIB’s deputy chairman. “To speed up such transition we shall keep on providing consultancy and investing more and more in innovative models of circular economy and in new technologies, as well as in more traditional projects of resource efficiency.”

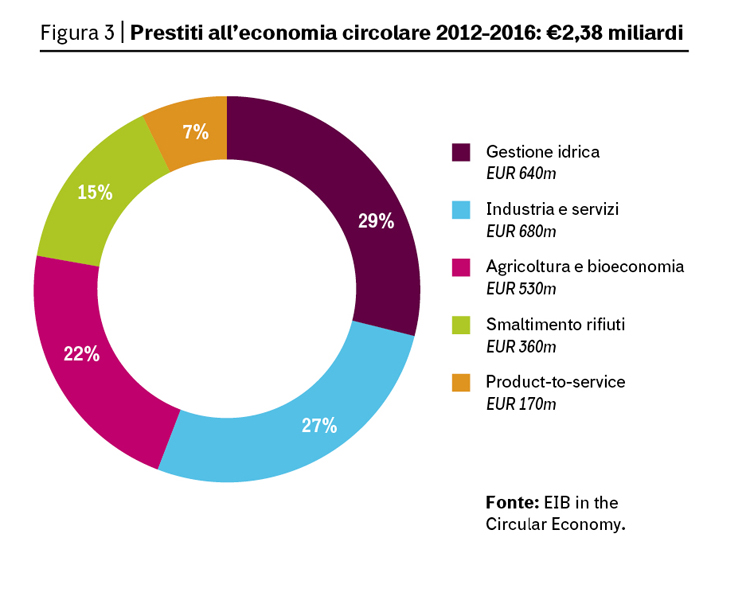

Over the last five-year period, EIB shelled out 2.38 billion in loans to European small and medium enterprises committed to the circular transition (see figure 3). But the same European bank reminds us that future outcomes will depend on how much Europe will be able to multiply resources: “Full implementation of current solid waste directives alone – EIB points out – will require investments of more than €40 billion by 2020.”

The Green Bond is Booming and not just in Europe

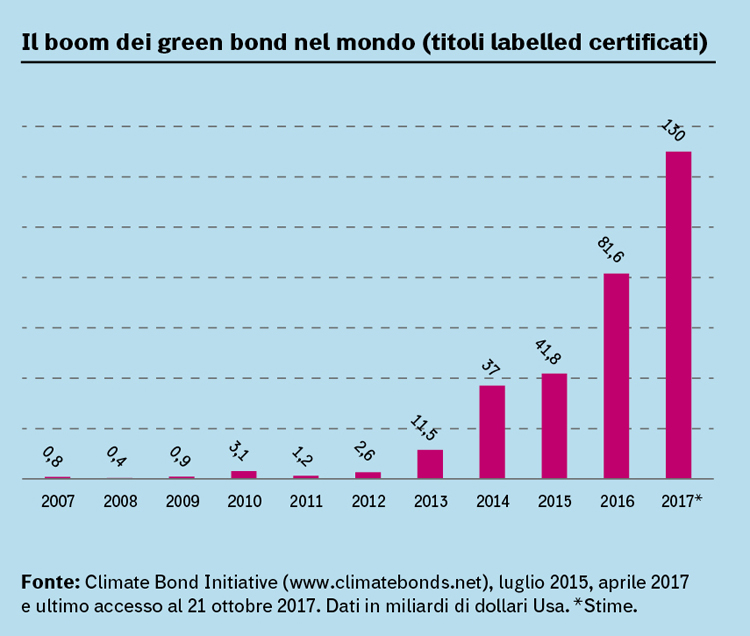

A quantitative estimate of this phenomenon can vary considerably according to the definition adopted, but one thing is certain: in the world of responsible finance, few product categories managed to capture the attention of mainstream analysts and media as green bonds did, the fixed income stocks thought to fund projects, enterprises and initiatives aimed at, in one way or another, to protect the environment and fight climate change.

Anyhow, their value, in Europe alone, is not lower than €178 billion. Calculations, carried out on the basis of data supplied by the London-based NGO Climate Bond Initiative, are included within the 1st Report on Ethical and Sustainable Finance, presented by the Ethical Foundation Finance last November to the House of Commons.

The European one is only a fraction of the world movement exploded mainly thanks to the interest shown by the sector by private investors, starting from 2013-2014. Worldwide, according to the most recent estimates by CBI, green bonds in circulation amount to $895 billion. Registered bonds are 3,493, issuers are 1,128. The most involved sectors include transport with low CO2 emissions (554 billion equalling 61% of the total) and the segment of clean energies (173 billion, 19%).

Throughout 2016 the total number of green bonds soared by $201 billion thanks to 138 billion of new emissions by already operating placement agents and 144 billion from first-time operators, minus 81 billion bonds that ended their cycle by reaching maturity. “Such figures – underline the authors of the report – highlight the persistent trend of exponential growth that has characterised the market for some time now.”

The labelled green bond sector (bonds meant to fund environmental projects or pertaining to climate change which have been labelled as “green” by the issuer, editor’s note), and that of certified bonds according to CBI’s Climate Bonds Standards, the issuances registered at the end of 2017 should reach $130 billion compared to 81.6 of 2016 (see diagram).

Top image: Karen Arnold/www.publicdomainpictures.net