Top image: Details of Besani’s knitted textile.

“Is it progress if a cannibal uses a fork?” John Elkington is asked at the beginning of Cannibals with Forks, one of the most important books on sustainability published in 1997 where the triple bottom line principle is formulated for the first time. Elkington answered the question positively: if cannibals, who, in the metaphor, represent big companies that try to “devour” one another, use a fork, that is, adopt sustainable production models, will they really progress?

The question also applies perfectly to fashion. We, indeed, say that fashion is cannibal, affected by a sort of reverse Cronos Syndrome. In fashion, children – new collections and trends – devour fathers – the collections and trends of the previous season – making them obsolete, unfashionable and eliminating their commercial value. We could register fashion’s cannibalism as a perfect example of planned obsolescence, as Catherine Rampell wrote on The New York Times in a 2013 article where she provocatively invited brands like Apple to imitate fashion’s consumer brainwashing every new season to convince buyers to purchase something new. There must be some truth to it. But something more than that too, as is clear if we compare fashion with a “pure” creative industry such as publishing or cinema: could we perhaps claim that the publication of a new novel or the production of a new film is a waste caused by planned-obsolescence strategies initiated by editors and producers? Can we stick to reading or seeing the classics again? The need for new products is innate in creative industries and the hybrid fashion industry has inherited some of their DNA. It is difficult to imagine a world where the need for innovation and the cultural and symbolic aspect – in short, fashion – does not have a lot of influence on how we dress and where clothing is merely a functional feature.

Unlike “pure” creative industries, such as cinema, music or publishing where production is mainly immaterial, fashion consumes great quantities of materials. Actually, it is the materials which attribute an aesthetic and symbolic value to the garments: the style of the dress, the textile’s feel, its lightness, more or less gleam or brighter or less bright colours – it all depends on the materials used or the industrial processes which the materials have undergone. The book Neo-materials in the circular economy: Fashion deals with the matter of the tension which is generated between the material and manufacturing aspect and the continuous need for new products which fuels fashion and material consumption.

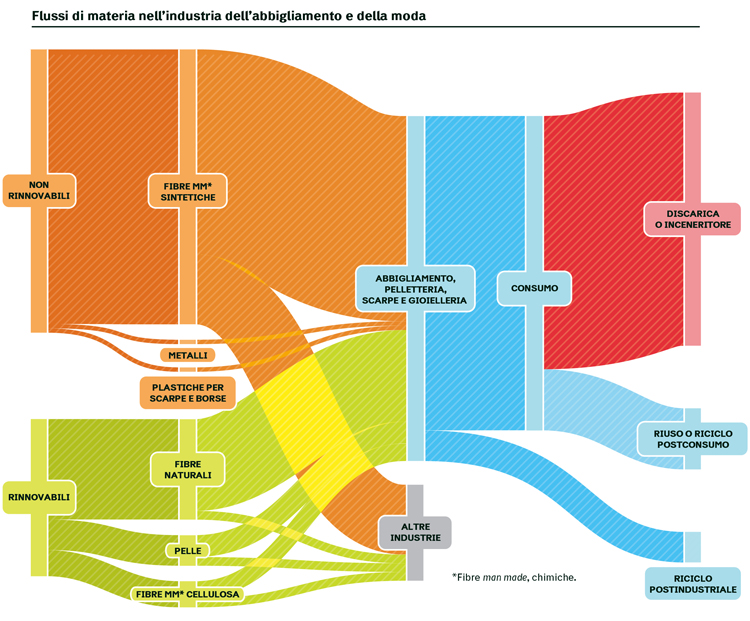

|

|

Source: sustainability-lab on data from CIRFS, UN Comtrade; FAO Leather compendium; FAO, Jute, kenaf, sisal, abaca, coir and allied fibres statistics; World Silver Survey. |

|

|

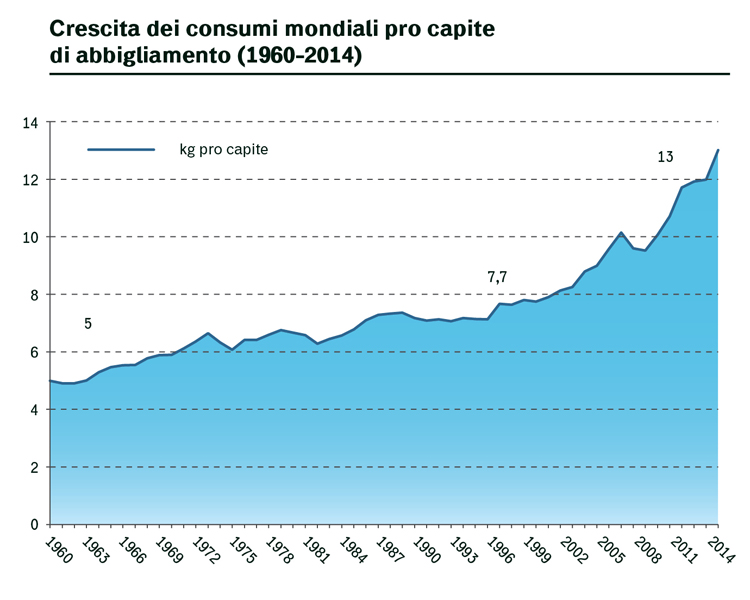

Source: sustainability-lab.net on ICAC- FAO World Apparel Fibre Consumption data, different years and UN Population Prospects data. |

The problem is clear, but what about the solutions?

Material “waste” innate in fashion cannibalism has a negligible impact when, at the end of the 1800s, American sociologist Thorstein Veblen described it as a distinctive attribute of the well-off, that is, a concern limited those he identified as the leisure class. The impact began to increase in the 1970s with the development of prèt à porter – while a French term, the revolution took place in Italy – that boosted access to fashion, opening it up to a wider public and making it a global phenomenon. And it finally exploded at the start of this century with the fast fashion boom, allowing everyone to have the latest fashions at a minimum price, furthermore accelerating product obsolescence cycles. Income growth and increased consumption in recently-industrialised economies has contributed to making the explosion of fashion material consumption even more dramatic. Consider, for example, China, where clothing consumption, net of price increase, almost quadrupled between 2002 and 2015, according to China Statistical Yearbook data published by National Bureau of Statistics of China.

The extent of the change that has been generated over recent years is evident in data on consumption per capita of textile fibres which have grown over the past 15 years from around 8 kg per inhabitant in 2000 to around 13 kg (+68%), more than they had risen over the previous 40 years, since in 1960 the figure was around 5 kg. Using the same materials, technologies and processes, every extra kilogram consumed results in a corresponding increase in consumed energy, chemical substances released into the environment, and depletion of non-renewable materials.

These simple figures highlight a problem which is now recognised and all fashion’s stakeholders agree on its importance. Solutions cannot however be settled on.

On one hand, a change in consumption models is called for, along with a radical limitation of fashion “cannibalism,” reduced obsession for new products which would translate into less consumption and less material waste. If mass cannibalism fuelled by low prices is the cause of the problem, they say it cannot be part of the solution. Another point of view, instead, assumes interest in fashion, and the early obsolescence of products that inevitably derives from it, to be a plain and simple fact – except some excesses which deserve a limit – and that the solution must be found with the introduction of new, more sustainable technologies and circular economy models. That is, by equipping cannibals – fashion designers and producers – with forks, as Elkington would say. According to this view, the key words are: recycling, reduction and reuse of waste as well as elimination of substances and processes which pollute or have a high environmental impact.

A change in paradigm: the main players of more sustainable fashion

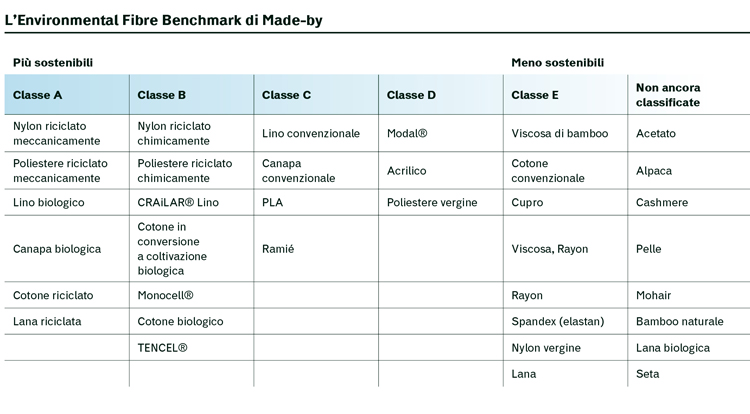

The analyses and good practice cases presented in Neo-materials in the circular economy: Fashion are an official stance in favour of the second point of view which is not only more realistic, but can generate positive effects within a short space of time. Actually, it has already started producing them. The book collects examples of the sustainable use of materials in fashion production which have established themselves on the market over recent years. After the presentation of the sustainability evaluation model for textile materials proposed by Made-by, one of the international points of reference for sector companies, in the chapters dedicated to non-renewable and renewable materials, recycling, water and chemical substance use, come 14 company stories about the adoption of more sustainable technologies and processes by the fashion production chain’s main players: fibre producers, yarn spinners, textile producers, dyers, and water management plant producers. These are true success stories featuring small and large companies, some of which were recently established and others with histories dating back a century. They are all cases of “efficient fork use.”

|

|

Carmina Campus – Rings made with two gold-dipped tin can ring pulls and two different coloured imitation gemstones; can be worn on one side or the other. |

The chapters on niche or emerging brands and leading big international brands, on the other hand, describe a partial map, limited to several illustrative cases, of fashion brand initiatives and profiles, the end users of materials, that are making the fashion market scene more sustainable. This sector is crucial considering that it is the demand and decisions of fashion brands to condition the behaviour of the whole supply chain.

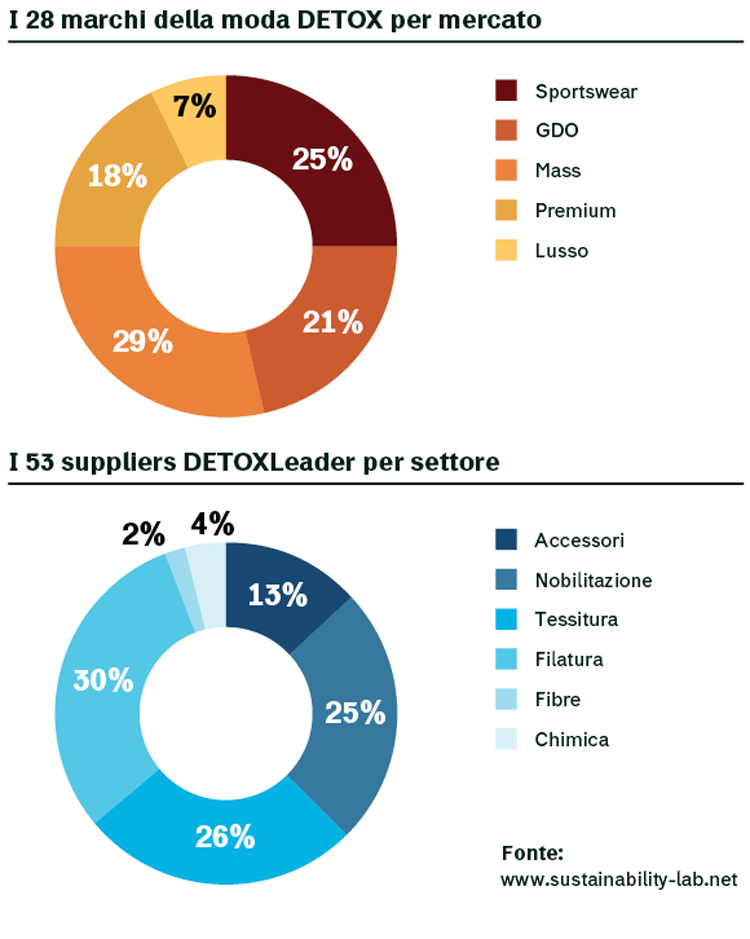

One of the central players in this change is Greenpeace, the NGO which, in 2011, launched the Detox my Fashion campaign to free fashion from hazardous, polluting chemical substances. Without a doubt, this controversial campaign was a blow to the sector, unexpectedly speeding up the journey towards sustainability.

Awareness of fashion’s environmental impact has risen, above all over the past decade, exploding suddenly, like a sort of unexpected tsunami. Matters and awareness that just a few years ago were completely inexistent in the sector – that, compared to others, began to deal with the issue late on – or limited to extremely small niche markets, are now essential for all big market leaders and are included in the most important magazines and at designer catwalk shows. This tsunami suddenly drove fashion onto new terrain, even if still in a confusing way, full of contradictions, with contrasting forced solutions and resistance, utopian, conservative behaviour, accelerations and decelerations, in an overall context with no consolidated structure as of yet.

|

|

From Somewhere with Speedo – Creative project by Orsola de Castro and Filippo Ricci, in collaboration with Speedo. Dress produced reusing materials from Speedo LZR Racer competition costumes, which went unsold after the changes made to international swimming competition regulations. Limited edition, presented at Estethica 2011.

|

What if sustainable fashion were cool?

“Helping the planet doesn’t have to be painful” the organiser of a sustainable fashion event answered many years ago in an interview. This matter is still relevant today and the awareness of consumers and end users is still a critical element. Large-scale environmental and social justice campaigns, from Greenpeace’s Detox my Fashion to those following the tragedy at Rana Plaza in Bangladesh which caused the deaths of over 1,200 workers who sewed garments for a great number of big brands, prompted sudden, greater awareness. However, the percent of those willing to pay a greater price for a more sustainable product has remained stable at between 10 and 20% of consumers, proving how difficult it is for the story behind the product to come to light.

Nevertheless, there is a new phenomenon, yet to be completely analysed, which involves fashion’s ability to inspire behaviour: products made with sustainable materials and technologies are starting to become cool. Recently an online magazine for young people who love urban night-life and the coolest parties – the world which is perhaps the furthest from traditional sustainability values – gave an example of this with a product, a trainer which is described as “already one of this season’s must-haves.” No reference is made, however, to the product’s sustainability. This is a contradiction which probably opens up a debate which will create division in the field of those who desire a more sustainable economy: can the same phenomena and the same mechanisms, fashion and the megabrands, which are, mostly, at the root of the problem, also become a part of the solution?

|

|

Make/Use – Some patterns and illustrations from the collections which show the Zero Waste Design technique and garment versatility. |

If not now, when?

It is time. We have already crossed a boundary in the fashion industry and it is difficult to turn back once we have begun the journey. Some time ago, Rossella Ravagli, head of Gucci’s Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability Department, reminded Copenhagen Fashion Summit during a presentation that sustainability is a one-way journey, requiring investment into and organisational models for production chains which are difficult to accomplish, but which, for this very reason, are difficult to abandon once achieved. The principle expressed by fashion designer Bruno Pieters that “the story behind the design is as beautiful as the design itself” has become part of the fashion system.

We are lucky to be part of this movement, that still has a long way to go, but it is now a fundamental value for fashion.

Catherine Rampell “Cracking the Apple Trap”, The New York Times, 29 ottobre 2013; tinyurl.com/q6pyykl

Made-by, www.made-by.org

Marco Ricchetti (edited by), Neo-materials in the circular economy: Fashion, Edizioni Ambiente, 2017; tinyurl.com/yaqb6njw