Can we build a smartphone that is made to last, without having to choose between quality and production-chain ethics? There is no doubt in the Dutch Fairphone offices: the answer is yes. For a number of years, this constantly-improving company has been making consumers and big companies aware of the hidden costs of modern production. Fairphone is now a B-corp, a certified benefit corporation with 70 employees in the heart of Amsterdam. However, the first ethical smartphone’s journey began back in 2010 when Bas van Abel, the company’s current CEO, launched an awareness-raising movement relating to a more ethical electronic-device production chain. The movement, originating from the Waag Society, a Dutch foundation involved in experiments concerning art, science and technology, proposes itself as an awareness company.Over the course of several campaigns and laboratories, hundreds of smartphones have been taken apart to show consumers the complexities and incoherences hidden between the screen and the casing.

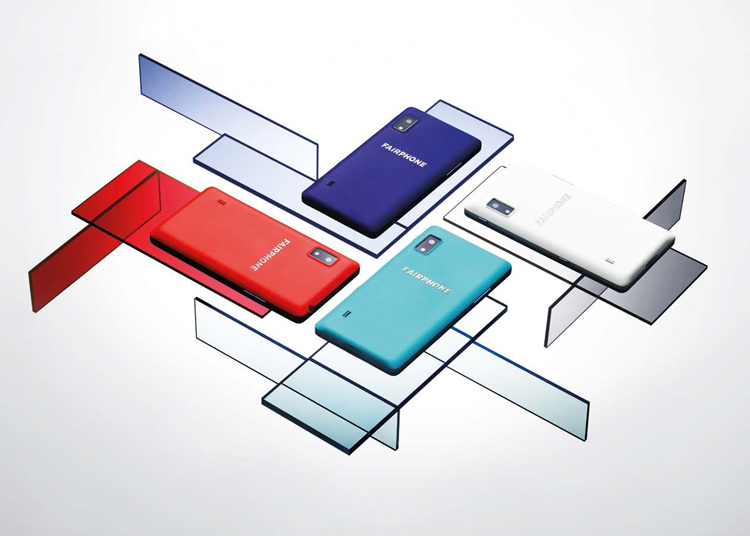

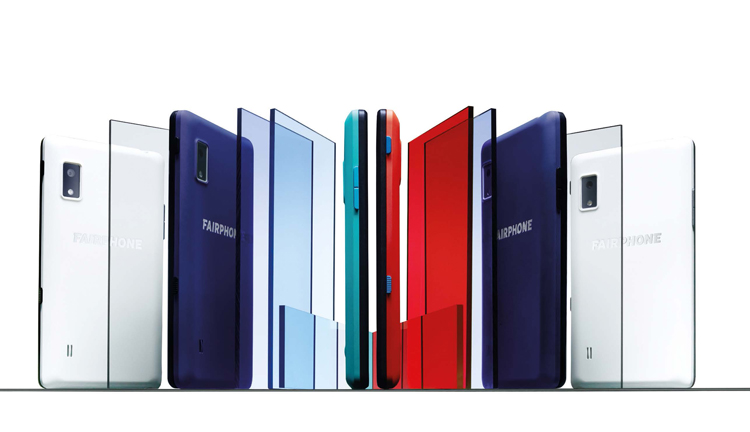

But, by 2013, awareness raising was no longer sufficient. Founder Bas van Abel and co-founders Miquel Ballester and Tessa Wernink decided it was time for action. A €400,000 seed investment into hiring the company’s first employees and a crowdfunding campaign completed the picture. With a focus on metal and mineral sustainability, the Fairphone 1 came to be, selling double its initial target. At the end of 2015, the Fairphone 2’s launch further raised the bar no longer with the sole objective of sustainable material use, but also of stretching product life through modular design.

Material Origin

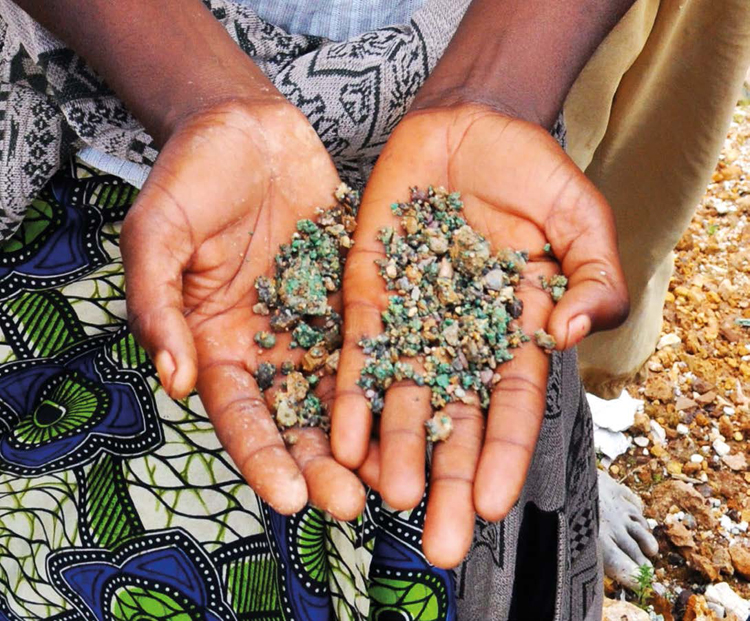

The minerals and metals in common smartphones reach the supply chain from the mineral sector. This demanding industry is rarely sustainable for the environment and workers. Fairphone was created with the objective of certifying the ethical origin of all the materials contained in smartphones. Specifically, the aim is to trace back along the production chain in order to analyse the materials and discover the connected critical elements.

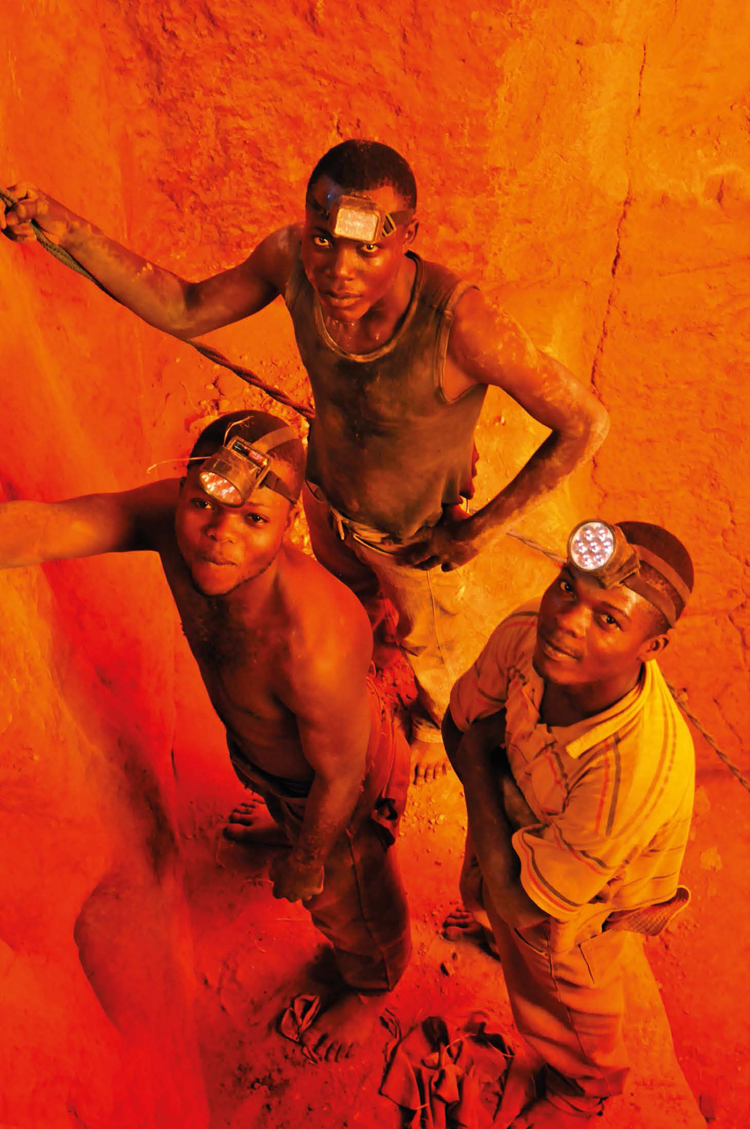

So-called conflict minerals and their derived products are the first focus in this process. The company’s interest arose also following “Section 1502” of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, regulated by the SEC (US Securities and Exchange Commission) in 2012 and approved by the United States Congress, which was intended to discourage the use of minerals from (or extracted from) the Democratic Republic of the Congo and/or neighbouring countries (Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia). With the original objective of preventing the electronics industry from funding violent conflicts in Central Africa, the Dodd-Frank Act ended up indistinctly damaging both clean trade and otherwise, with the unintended consequence of extractions in these countries being halted by many companies. The negative result was that even more people, now unemployed, ended up enrolling and taking part in the conflict.

Fairphone accepted the challenge of sustaining economic development and responsible extraction practices in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but there is more. After years of local work and industrial collaborations, the whole production chain can be traced back to mines where four conflict minerals (tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold) are extracted.

The Fairphone 2 contains forty different minerals. Along with The Dragonfly Initiative, Fairphone has developed a reference system for evaluating 38 of these materials and the relative opportunities and problems generated on a social, environmental and health level.

The tungsten industry (used to create mobile phone vibration systems), for example, involves twenty different companies. In order to achieve conflict-free tungsten, the whole chain has to be traced back, via the refinery in Austria, to mines in northern Rwanda.

Modular, Long-Lasting Design

The Fairphone is an open book, not an incomprehensible black hole which cannot be decomposed as is the case for many electronic devices. Owners can easily understand how it works and change the parts over time. All the parts of this modular box are replaceable (battery, screen top and bottom module, which contain the rear camera, head phone jack and USB port for instance).

When you open a Fairphone up (which can be done in just a few seconds), there are six distinct modules, each of which can be replaced autonomously in the event of faults and/or can be bought separately. Online tutorials offer assistance on repairing the most commonly damaged parts.

This modular smartphone also has the potential to be upgraded and developed. The Fairphone’s expansion port, which is connected to the rest of the phone, allows for integrating additional functions.

From a software point of view, it goes without saying that the Fairphone source code is open to owners and developers.

Working Conditions

Initially focusing on the environment, Fairphone’s scope has extended and now incorporates workers’ conditions and the protection of human rights in supplying companies.

China is the largest smartphone producer in the world, manufacturing 771.4 million in 2015. At the same time, China is well-known for its bad working conditions and low salaries. In order to continuously improve conditions for the workers involved in the production chain, Fairphone works closely with its suppliers, using local experts and putting its direct employees in the company. At the beginning of the trade relationship, Fairphone performs a transparent assessment of the company (based on working hours, safety, workers’ representation, etc.) and the problems detected. This assessment becomes a starting point for a joint development plan. Improving the existing processes within the supplying companies is one of Fairphone’s strong points. It is a delicate job, also considering the many factors to be balanced: the economy, workers, local laws and how all this interacts. It is essential to have a complete understanding of certain trade practices. This is a constant learning process for Fairphone and its local partners.

Absenteeism during specific periods and high turnover are, for example, some of the critical points which have been most detected in producing companies. In China, these critical points coincide with Chinese New Year celebrations. At this time of the year, many workers receive cash bonuses and return to their families in their villages relatively rich and then do not go back to the factory since they are thinking of getting a new job. So, when the factories open up again, the company owner has to invest huge amounts into training to avoid risking lower production quality. Keeping the worker in the factory is fundamental.

These are hidden problems which change from area to area. Fairphone is trying to resolve them, along with other partners, experts, researchers and NGOs, by developing innovative programmes which increase worker satisfaction and representation and favour communication between workers and managers.

Product End-of-Life

Maximum exploitation of the materials used in consumer electronics, repeated reuse and recovery of as much as possible form another Fairphone cornerstone.

A study currently underway is examining the effectiveness of different ways of recycling the Fairphone 2. Its results will be shared with the whole sector and will help manage the conclusive lifecycle phase of current products better and improve the design of those to come.

Today, along with its local partners, Fairphone supports telephone collection in developing countries, sending them to Umicore, a Belgium company known for its efficient recycling processes. This is a perfectible process (sending telephones from Ghana to Europe is not very sustainable, after all), however it is always better than seeing precious materials disappear from the production cycle forever, abandoned or wrongly disposed of.

In the long term, Fairphone aims to create local jobs with on-site recycling and plants. This project is partly hindered by informal recycling practices, above all as regards copper, in some developing countries. This is an ongoing, developing process, and completely Fairphone-style.

Fairphone’s transparency along the value chain, from material extraction to smartphone design and construction, until end-of-life and new client relationships, has had a positive impact that goes beyond the 135,000 smartphones (80,000 Fairphone 2) sold until now.

While the market makes way for companies based on ethical values, Fairphone is changing the way products are created and seen.

The Dragonfly Initiative, thedragonflyinitiative.com

Where do the materials of a Fairphone come from? www.fairphone.com/en/how-we-work/mapping-phone-made

The real, detailed costs for producing and marketing the Fairphone 2: www.fairphone.com/en/our-goals/how-we-work/fairphone-cost-breakdown

Info

Interview with Miquel Ballester, Fairphone cofounder Product & Resource Efficiency Manager

by A. I. T.

Because a Telephone Cannot Be Forever

From your point of view, in addition to materials and working conditions, what industry elements need changing?

“I believe that a very interesting matter, which is not spoken about enough, is client companies’ procurement. They get supplies in producing countries like China or Bangladesh. In developed countries, everything is decided very quickly and orders are changed just as fast, so suppliers end up crushed. Let us take the fashion sector as an example. If a designer suddenly decides to change the colour of a shirt’s buttons, the suppliers have to change all the shirt buttons and they do not have enough bargaining power. This results in work peaks that do not allow suppliers stable production. The same goes for the Christmas peak, which the production industry experiences between September and October. These peaks of work are a nightmare. Producing companies need to hire new employees that have to be dismissed at the end of the period. This mechanism is the outcome of how the supply system is organised by multinationals enjoying disproportionate power.”

How can we change this mechanism?

“Consumers also have great power. They need to understand that the situation is much wider-reaching than what they see on the market. The consequences behind buying a €3 T-shirt must be understood. These consequences multiply for a smartphone with hundreds of elements inside, built by many different companies which the consumer is never in contact with. In this regard, we have programmes currently underway on social and environmental sustainability, along with the six or seven most stable companies of the production chain.

“Another thing to do would be simply eliminating Christmas marketing campaigns. We could do a campaign in November and explain why. Inventing a new Christmas in October would be the perfect gesture to make to our suppliers. What is more, we could simply accept that our telephones have a little scratch. That way, we would contain a good amount of waste created in the production phase, due merely to aesthetic reasons.”

Can a telephone last forever?

“No, it is impossible. This is a defeat but that is the way it is. From a technical point of view, a smartphone can last a really long time if you analyse its hardware. In any case, the obsolescence problem derives from suppliers that stop producing a certain chip and, at the same time, stop providing software support. Every time that Android releases a security patch which must be installed, a chip or camera producer is needed to create the software portion that controls this component. If this software portion is not created, the product can no longer be updated. Thus, it become insecure resulting in the software part no longer working while the hardware part works. Suppliers are an element of risk. The further we look into the industry, the more suppliers we find because suppliers, in turn, have their own suppliers that create individual elements. The wider the radius, the less control we have.

“Managing this complex system is a great challenge which we, as Fairphone, are obviously interested in. In any case, in order to have greater control and bargaining power we must increase sales. Focusing on scalability allows us a more comfortable position in terms of liquidity but, it makes us a more interesting company for suppliers, partly in terms of our influence on the production chain.”

What limits the current system? Where can we improve?

“Product design must allow individual elements to be disassembled quickly in order to direct different materials towards the best recycling line. We can currently recycle only 40% of a smartphone. Magnesium, for example, found in the back of the screen, is currently completely wasted in the foundry. If screens were removable, we could put the magnesium through another type of process, recovering 80%.

“Durability-based design is totally detrimental to repairability. A waterproof telephone is very difficult to repair. On the other hand, a repairable telephone is certainly not water resistant. It is difficult to design based on repairability and modularity. It is all a matter of balance. We decided to take the challenge to extremes, showing that the screen can be removed in ten seconds. It has been an enormous amount of work, but we have achieved a great goal.”