Over the past few years, a trending environmental issues has been that of marine litter. It is a problem affecting many countries around the world. Contrary to what usually occurs, marine litter is not caused directly by industrialised countries, but rather by industrialising ones. According to The New Plastics Economy report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, only 2% of marine litter stems from Europe and the United States.

Reducing the total amount of marine litter meets several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): in particular Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and Goal 14 (Life Below Water). According to the European Commission, 80% of plastic in the oceans comes from land, whereas only 20% originates from water-related activities. Dispersion of plastic and other materials into the sea is often caused by lack of infrastructure. Hence, it is imperative that the relevant facilities for waste management be developed and made accessible, especially in South East Asia and China.

Recent research suggests that Asian countries are responsible for 80% of ocean litter.

Therefore, improving infrastructure and waste collection facilities in countries most responsible for marine litter is the best solution. However, while infrastructure is being improved and positive practices are being defined, we need to reduce the current amount of marine litter. Not an easy feat, especially when considering estimates that suggest that the sea will contain a greater mass of plastic than fish, by 2050.

Currently, many programmes to help us change course are being implemented. These range from the UN Global Partnership on Marine Litter, to Marine Litter Watch (MLW). The latter involves a model – which includes a mobile app – developed by the European Environment Agency, combining citizens’ participation with modern technologies so as to narrow the information gap on marine litter found on beaches: an important aspect for the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive.

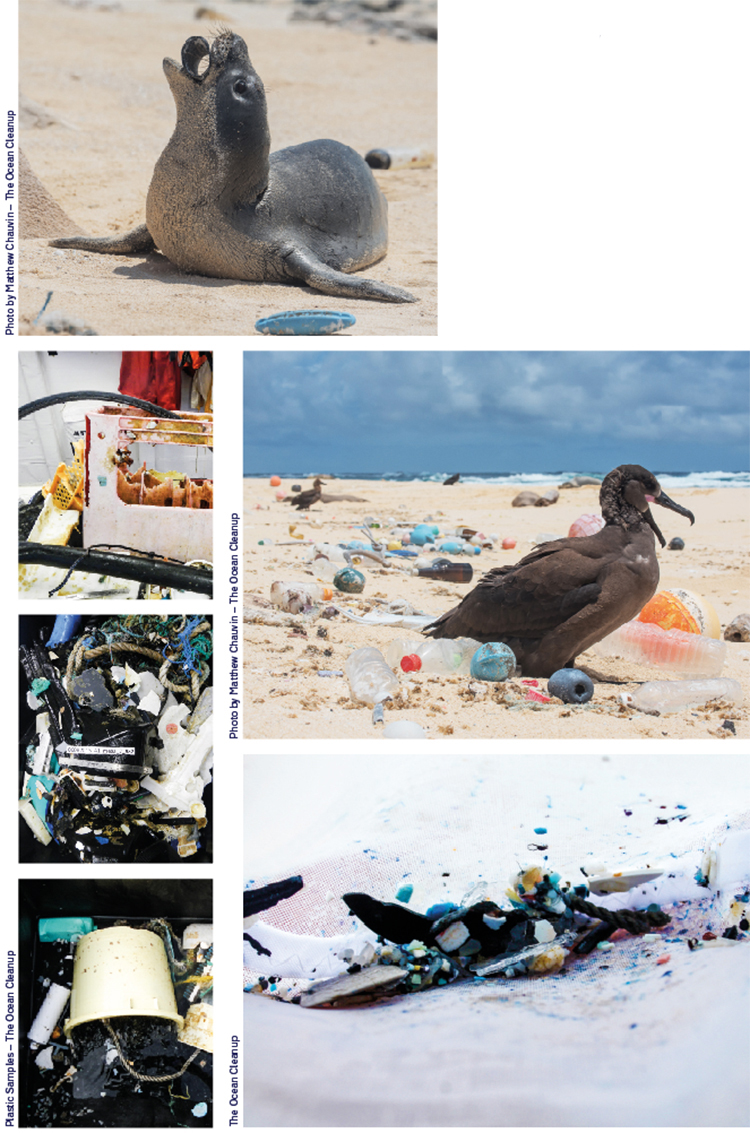

Separately from actions by institutions and political bodies (including local political entities, foundations and international organisation), there are countless initiatives by ordinary citizens, European partnerships and multinational corporations that all share the common goal of keeping plastic out of our oceans and seas. The survival of the ocean’s ecosystem, the health of marine species and the wellbeing of seaside communities that rely on seas and oceans are not the only aspects at stake. In actual fact, all of mankind is put at risk by marine litter.

Recovering and turning marine litter into environmental and economic value is the next step that companies and projects around the world are taking to solve the problem. Of course, it is a long-term solution. As many activities have only just started, the actual results will only be noticeable in the long run.

UN, Global partnership on Marine Litter; tinyurl.com/yboxvndt

EEA, “Marine LitterWatch in a nutshell”, 2015; tinyurl.com/ybsze67f

The Ocean Cleanup

One of the first people to engage in a large scale clean-up of the ocean was the Dutch 23-year-old Boyan Slat. When he was barely 19 he gave up his studies in engineering so as to embrace The Ocean Cleanup, an initiative that focuses on developing the necessary technology to clean up the ocean. After years of research and millions of dollars spent (since 2013 The Ocean Cleanup foundation has collected a staggering 27 million euros) there is now a network of long floating barriers that behave like a man-made coast, and allow natural ocean currents to concentrate plastic, thus simplifying collection. Following the first prototype in June 2016, by mid-2018 the first fully operational system in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (the largest ocean waste island: a stockpile of debris made up almost entirely of plastic waste, and located between Hawaii and California, author’s note) will be launched. A full scale deployment of The Ocean Cleanup system, could clean up to 50% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 5 years.

The Ocean Cleanup, www.theoceancleanup.com

|

|

|

The Ocean Cleanup

|

Next Wave

Next Wave was created with the aim of intercepting plastics on key ocean-bound waterways. In fact, it is estimated that 88-95% of plastic in oceans comes from only 10 rivers. Next Wave also aims to create the first cross-industry commercial-scale global ocean-bound plastics supply chain, by processing materials collected from river and coastal areas and making them available for use in the products and packaging of partner companies.

The companies that contributed to creating Next Wave – an initiative that is now managed by the American incubator Lonely Whale – include multinational corporations such as Dell Interface, General Motors and Herman Miller; all of which have operated within the circular economy for a number of years. The companies involved benefit both socially and economically, since supply chain security is accompanied by high social and environmental standards.

Last December, the first product stemming from the project was presented: an ergonomic office chair manufactured with almost two kilos of recovered plastic and devised by the founding partners Bureo and Humanscale. In the next 5 years, the consortium intends to intercept over 1.5 million kilos of plastic and nylon fishing gear, the equivalent of 66 million bottles of water, that would otherwise end up in our oceans.

Next Wave, www.nextwaveplastics.org

|

|

|

©Interface

|

Circular Ocean

The European Union is also taking a closer look at the problem of waste in oceans and seas. Recent conferences on the issue and the Strategy for Plastic adopted last January are proof of it. EU-funded projects pursuing innovative and sustainable solutions for plastic marine litter include the Circular Ocean project. Developed in the Northern Periphery and Arctic Region (NPA), the project encourages companies and entrepreneurs to develop new products and experiment eco-innovative solutions, generating income by recovering materials that are discarded by the fishing industry. Furthermore, Circular Ocean aims at quantifying the environmental impacts of lost or abandoned fishing nets in the area.

The research scientist and project partner of the department of Ocean Operations and Civil Engineering at the Norwegian University, Dina Margrethe Aspen, claims: “Even though a great deal has been done to eliminate the problem of ghost nets, a lot can still be achieved through enhanced collaboration amongst industrial players, governmental agencies and research institutes. We believe that interaction amongst stakeholders is key to establishing such collaboration. What is lacking at the moment is an action plan leading to efficient management of resources in fishing gear. Such plans should prioritise a variety of actions aimed at eliminating, reducing or reverting the flows of equipment being abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded; thus ensuring the recovery of as much material as possible.”

Many institutions are involved in the transnational project, including: The Environmental Research Institute, North Highland College UHI (Scotland), Macroom E (Ireland), The Centre for Sustainable Design, University for the Creative Arts (England), Arctic Technology Centre (Greenland), Norwegian University of Science and Technology (Norway).

Circular Ocean, www.circularocean.eu

|

|

Circular Ocean

|

Healthy Seas

Healthy Seas has been operational for a few years now and has had a noticeable impact on the market. It also deals with the issue of ocean waste as a menace to marine biodiversity. Healthy Seas was created through a European joint venture of fishing companies, NGOs, governments, companies and communities involved in recycling, production and recovery. It collaborates with fishermen and local communities to prevent waste generation and increase sustainability in the sector. At the moment, there are three pilot projects in the North Sea, the Adriatic and the Mediterranean, all of which are very important regions for tourism and biodiversity, whilst being massively over-exploited for fishing. Fishing nets which are left unused are recovered, cleaned and turned into secondary materials. These are then used by the Italian company Aquafil to create Econyl®, a nylon yarn made with 100% regenerated waste materials used for swimwear, sportswear, underwear and even carpets.

Healthy Seas, healthyseas.org

|

|

|

Healthy Seas

|

Top image: The Ocean Cleanup