In Netflix's ironic and apocalyptic blockbuster Don't Look Up, a comet is determined to crash into Earth. Leonardo DiCaprio portrays an astronomer stuck somewhere between terrified and dumbfounded: instead of destroying the looming threat, the U.S. government, piloted by an entrepreneur with a big appetite for profits, wants to jeopardize the survival of the human race in order to extract valuable raw materials from the killer comet.

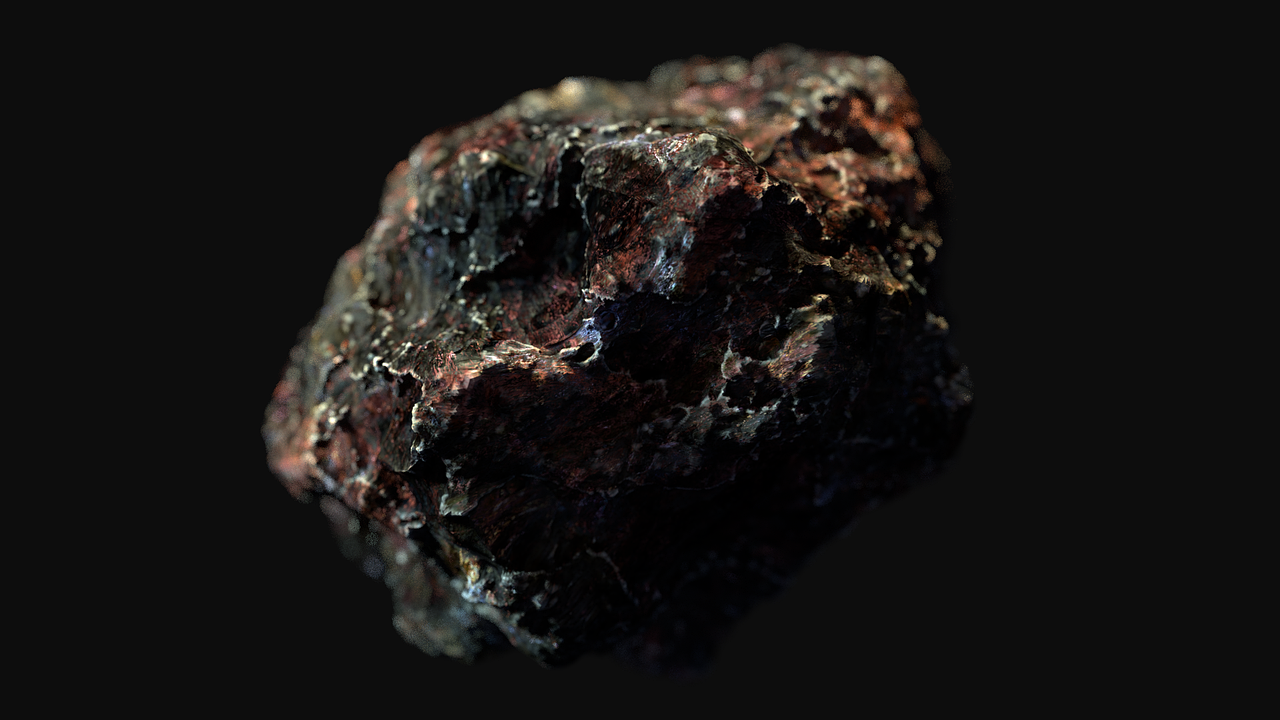

There is always plenty of science in science fiction: asteroids are really traveling celestial treasure chests, hopefully not destined to end up on our heads. Mines of gold, but also of iron, nickel, rare earths highly coveted as they become less and less available in this remote fragment of the universe.

Long ago, Goldman Sachs calculated that large intergalactic potatoes, on average, could each hold the equivalent of $50 billion worth of platinum. An overabundance that can explain why space mining, the frenzy to improvise as miners among the stars, is a frontier that appeals to so many. From historic space agencies to ambitious startups with evocative names, from AstroForge to TransAstra, all working to turn vision into business: the next big thing is floating up there above our heads.

The 1 billion euro asteroid

One asteroid in particular, lysergically baptized 16 Psyche, contains such an abundance of gold that, on a horizon of an ecumenical redistribution of its wealth (which is indeed science-fictional utopia), it would allot every inhabitant of this planet a dowry of more than 1 billion euros. “The number itself is worth little. First off, because the resources would not come all at once, but would be available a fraction at a time. And then, the increased supply would cause prices to decrease proportionally,” reasons astrophysicist Simonetta Di Pippo, director of Sda Bocconi's Space Economy Evolution Lab and among the world's leading space experts, with a resume of experience that includes the United Nations and ESA, the European space agency.

“I call myself an astrodiplomath, I’m convinced that space is the solution for the future,” she quipped, dodging the lofty titles. On the other hand, her latest book, Space economy – The new frontier of development (Bup, 2022), in the cauldron of already current opportunities in a $469 billion industry, includes precisely space mining. The antithesis of a chimera. Just to give a few examples: in October 2023, Nasa will set off on a 16 Psyche exploration mission. “The first step will be to characterize it, to study what it has inside.” Making this entity, like others like it, less UFO: less unidentified flying objects.

Instead, American TransAstra is working on a novel approach to the epic of orbital drilling: instead of launching excavators with a built-in rocket, it has devised a sort of hovering cage. What does it do? It captures the asteroid and shatters it by harnessing the power of the sun's rays, obtaining and storing inside it water, gas and other useful components to be fuels for spacecraft.

“The idea of using asteroids as a kind of space truck stop, to allow spacecraft to refuel and reach farther away, is a possibility that is full of sense,” Di Pippo confirms, before adding a caution: “Such bodies will have to be handled very carefully, to avoid deviating their trajectory. To avert the possibility that they will go from harmless to dangerous, perhaps ending up heading toward Earth.” Otherwise, from fiction, the Netflix movie would become prophecy. And a happy ending would not be too obvious to expect.

Funding and regulations

One thing is certain: space mining is not a matter of if, but when. “The technologies and methods are there, we need to find the appropriate funding to develop and implement them.” Not least because, it is clear, the payoff would not be immediate, as much as medium to long-term, a mismatch that investors would not like at all.

Then the issue of regulation opens up, because the mainstay of the laws regulating the space are based on the principle of non-appropriation. To put it bluntly, one cannot wake up one day and decide to grovel an asteroid by snatching what it contains: “To this day, to launch any mission into space, one has to ask permission from national authorities, which should give approval only if the proposal is found to be in line with international treaties.”

It is to be assumed that the familiar names – the United States, China and Russia foremost among them – will not have too many qualms about forcing their hand in rewriting the key principles of the industry, especially if it turns out to be to their advantage. But before worrying about the infinitely large, meaning the geopolitical balances upset by a redistribution of raw materials (Africa would suddenly become marginal again, for one thing), we need to care about the microscopic: “There is a tendency to assume that these extracted solids or liquids do not contain anything harmful to human beings,” Di Pippo warns. “In truth, we don't know if it is prudent to let them come into contact with crews and, in general, with human beings.” Apparently, an interstellar quarantine may be needed.

What about the environmental impact?

It is one of the issues to be unraveled in sculpting the contours of space mining, along with defining its environmental impact. The coming and going of rockets heavy with raw materials does not seem like a very green scenario. “Therefore, in parallel, research must move in the direction of developing green or at least less polluting fuels. Weigh it all in a cost-benefit perspective.” Because, in fact, if you settle down and go drilling around Mars, you reduce the same activity on Earth and you don't even have to transport what you extract from one continent to another.

“Space should be seen as a key element in the fight against climate change,” the astrophysicist points out, highlighting the shift in perspective thrown wide open by this opportunity: “We are finally realizing that the space economy has fundamental spin-offs on our planet. It will be the accelerator for sustainable development.” Provided we are more forward-looking, and less greedy, than the characters in our movies.

Picture: Paris Saliveros, Pixabay