According to the United Nations, today, over a billion and a half people live in informal settlements and by 2030 that figure could soar to 3 billion. So, the issue of future circular cities is inexorably linked to the development of slums and their economies that, despite eluding official surveys, move huge matter flows in a necessarily and spontaneously circular way.

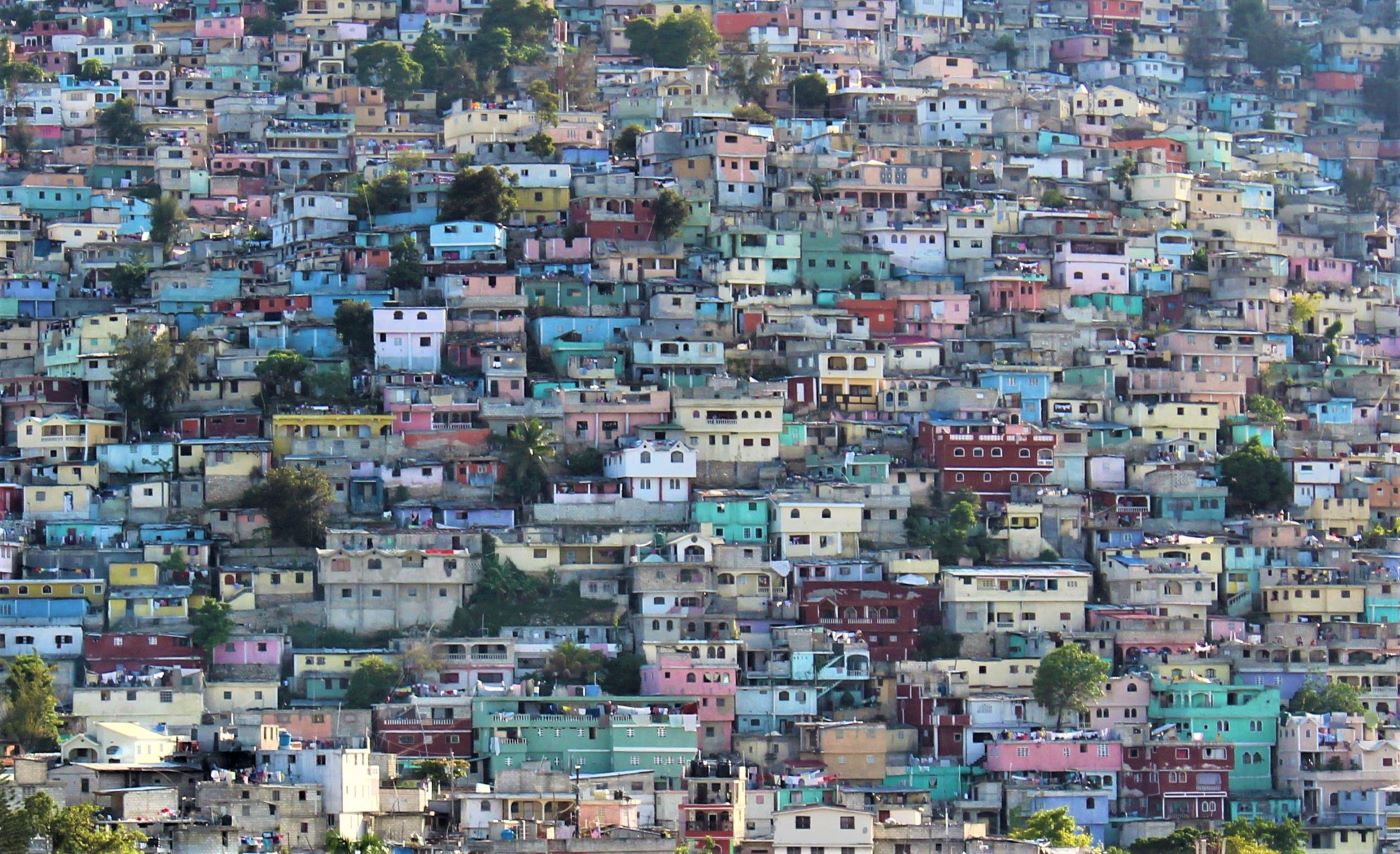

Kibera, Dharavi, Neza-Chalco-Itza, Khayelitsha, Cité Soleil, Makoko, Rocinha, Agbogbloshie are almost unpronounceable names that mean nothing to most of us. But if we associate them with the megacities of which they are the poorer and more sprawling appendices, a few images spotted in a documentary or newspaper immediately come to mind. Slums, shanty towns, favelas or informal settlements as they are technically denominated.

Kibera, on the outskirts of Nairobi – Kenya – with about two and a half million people; Dharavi, just outside Mumbai – India – (at least) one million; Neza-Chalco-Itza, north of Mexico City, is said to host a staggering four million people; Khayelitsha, near the airport of Cape Town – South Africa – 1.2 million. Cité Soleil, Haiti’s largest slum, just outside the capital city Port-au-Prince, 240,000; Makoko, next to Lagos – Nigeria – over 100,000; Rocinha, one of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, about 70,000; Agbogbloshie, the settlement born next to the world’s largest electronic waste landfill in Accra – Ghana – has probably a population of over 80,000 people.

According to the United Nations, currently, over a billion and a half people all over the world live in a slum or dwellings regarded as “inadequate”, and by 2030 that figure could reach three billion. These are obviously just estimates with some margin of error: we are talking about informal data that, by definition, escape census. What is certain, though, is that we are talking about big numbers that move huge economies. The latter, with no transitions forced from above, are spontaneously and necessarily circular. That’s because in Dharavi as well as in Kibera, recovering, recycling, reusing, sharing and transforming are a matter of survival.

The Informal Economy’s Invisible (and Circular) Flow

Mapping out the informal economy – and within it the circular one – is not an easy job. One can start from some macro information provided by ILO, International Labour Organization. According to a 2018 report, 61% of the workforce worldwide (about 2 billion people) consists of informal workers. By informal economy it is meant “the various economic activities, businesses, jobs and workers not regulated or protected by the government.” The definition has been elaborated by WIEGO (Women in Informal Employment: Globalization and Organization), an international association carrying out several studies on this subject.

Furthermore, WIEGO deals with debunking several myths about what is defined as – with covert criticism – “shadow economy”. One of them being that the “official” economy and the shadow economy travel along separate tracks. This is not the case, all the more so in the case of the subset of material recovery and recycling activities making up a key role for the livelihood of slums born on the outskirts of many large cities. “There is a growing understanding that the 20 million informal recycling workers, according to the ILO Green Jobs report, play a crucial role in providing sometimes the only waste collection available in some cities,” explains Sonia Dias, the association’s global waste specialist. So, waste pickers are not outcasts to be saved, they should rather be recognized the key role they play in the circular economy in urban areas. What can help the integration is the ability of self-organising into spontaneous or even co-operative associations. For instance – continues Dias – “In Pune, India, the cooperative SWaCH is hired by the city to provide doorstep waste collection. This scheme allows recyclables to be reclaimed from household waste and be diverted for recycling. In Bogotà, Colombia, waste pickers have secured rights to access waste materials by the Constitutional Court, which mandated that waste pickers should be paid for their services. In Brazil, many municipalities hire waste pickers co-ops to provide door-to-door collection of recyclables. In addition, through Brazil`s National Solid Waste Policy, waste pickers cooperatives are part of the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policy which allows these workers to contribute to improving circularity.”

Dharavi is an iconic case of circular symbiosis between formal and informal world. The mega-slum on the outskirts of Mumbai makes the wheel of economy roll up to $1 billion (data from a 2010 British documentary, but today it would certainly be higher), largely based on urban city waste recycling. Batteries, old computers and mobile phones, light bulbs, paper and cardboard, cables and wires and above all lots of plastic: hundreds or rather thousands of small businesses along Dharavi’s alleyways manage over 80% of waste of one of Asia’s largest cities. The Dharavi model has become a case study, so much so that many define it as “a plastic recycling goldmine.”

It goes without saying that to run large cities it would be easier to manage material flows and waste collection efficiently thanks to a map to get through it, which would also provide an idea of the scope. ICLEI network – Local Governments for Sustainability is working on that. It launched a platform for the development of a circular economy in urban areas. In Africa, in particular, it concentrates on three cities: Nairobi, Accra and Cape Town. “One of the major challenges that most African cities are currently facing is access to data that is properly collected and shared,” explains Jokudu Guya and Solophina Nekesa from ICLEI’s African hub. The Circle City Scan Tool features amongst the organisation’s activities, a pilot project aiming at creating a database for the implementation of a circular economy in these areas. “The tool provides data which is scaled to the metropolitan level based on national statistics. This has been helpful in giving a high-level estimate of what data is saying about each city, despite the limitations of the available data.” To expose the informal economy’s invisible flow, ICLEI puts in place less canonical tools such as photography. “Through the Hidden Flows competition – reveal Guya and Nekesa – we were able to exhibit the stories behind the unseen, less obvious urban resource flows, infrastructure, and people. A collection of quality data helping attach a meaning to numbers in order to inform the decision process.”

Not Just Recycling: In How Many Ways Can a Slum Be Circular?

In any slum, waste material recovery and recycling are not the only circular activities. If the circular economy is a wide concept ranging from repairing to second-hand market, from sharing to products as a service, from modular architecture to multifunctional use of spaces, then, an informal settlement could almost be regarded as a paradigm of such model.

“In any slum, everything is circular,” says enthusiastically Alfredo Brillembourg, Venezuelan architect, founder with Hubert Klumpner of Urban Think Tank that devoted most of his professional life to improving housing conditions of those living in informal contexts.

The architecture of such places, the way houses are built, the materials used and the way spaces are lived and shared are examples of circular approaches. “Let’s start from houses: they are modular and keep on expanding over the years as families grow – explains Brillembourg – The starting point is 5 m2 per person, going up to 15 or 20 when children come along. Then a storey is added, then another and a third while the ground floor is let out to business activities, while a vegetable garden is planted over the roof where rainwater is also collected.” Obviously, everything is built with recovered materials, and people help each other, piece after piece they even build roads and rudimentary sewers. “That’s what we call Pirate Urbanism which contributes to create a strong sense of community in informal settlements. One needs to look beyond such heap of dilapidated dwellings most people see: a slum is first and foremost a social fact.”

The sense of community, collaboration, are precisely the moral principles underpinning a true circular economy made of sharing of resources, services and space. In this respect, formal cities would have a great deal to learn from informal ones. “In any slum, space, both domestic and public is always multifunctional – continues Brillembourg – The main square, for instance, early in the morning is a farmyard where cows and chickens are fed but it is cleared just in time for the opening of shops and then in the evening it becomes a meeting place for celebrations.” Even the spontaneous forms of sharing economy, albeit dictated by necessity, rely on a close-knit social network: from sanitary facilities to public laundries, cables to power kitchens, everything is shared and everything happens in communal spaces, which would be problematic if there were not mutual respect, trust and tolerance.

Proximity is another important element to outline a 360-degree circular model. Urban planners have been working on this aspect for years, trying to redesign metropolitan geography that in an informal city built with a grassroots approach is once again the spontaneous expression of a need. Oftentimes, those living in slums also work in them and there’s nothing “smart” about that. There simply is not anywhere else to go. This, however, entails shorter distance to meet any other need such as food shopping or going to school. So, spontaneous cities, despite having hundreds of thousands of inhabitants, are organised around hubs, micro-cities saving time and energy for daily commute. “This is the model that should be copied even in our large cities – observes Brillembourg – by bringing the village inside the city.”

Looking to the Future: Retrofitting vs Redevelopment

In a vision of the world’s urban future, the development of slums must certainly be included. According to Brillembourg, informal settlements are nothing more than cities in their embryonic state. “What is generally defined as a slum – he explains – is a settlement with poor housing, often built by dwellers themselves and without legally binding property deeds, with no infrastructure and toilets in the house.” This ground zero, though, “is a start to improve and integrate with the rest of the urban fabric as it’s happened for instance with crumbling historical centres in many European cities. If slums such as those of Dharavi or Khayelitsha were equipped with safe infrastructure, adequate water supply and sanitary facilities, it would be the coolest place to live in.”

In a truly circular perspective, Brillembourg, as well as most organisations dealing with informal settlements, rejects the concept of redevelopment favouring one of retrofitting. With the former, as the Mumbai administration has repeatedly tried to do with Dharavi, entire portions of the slum would be razed to the ground while accommodating its inhabitants in twenty-storey buildings that would dilapidate within a few years, with ensuing waste of resources and destruction of the social fabric, which is the real asset of such places. The latter, retrofitting, is thus the way forward in order to maintain everything good while improving the rest. “Policy makers – explains WIEGO’s Sonia Dias – need to understand that livelihoods need to be thought of in parallel with urban governance, infrastructure and services in slums and informal settlements. The livelihoods of informal settlements can be improved through upgrading of shanty towns, ensuring land property, basic infrastructure such as water and electricity supply, road pavements, community services such as crèches and public laundries.”

Brillembourg looks even further, counting on the ability of leapfrogging, skipping stages, typical of developing countries (for instance with telephony, mobile phones were introduced without going through landlines). “We can create off-the-grid urban villages in their own right, totally sustainable and independent: with urban agriculture, solar panels, wastewater treatment systems able to irrigate plants. All designed as an autonomous system, as if we were on the Moon.” And, lastly, he goes back to imagining the city of the future, “a vibrant fusion between formal and informal. The new Utopia – he concludes – will be a combination between London and Mumbai.”

Image: Haiti, Port au Prince (ph Giorgia Marino)

Download and read the Renewable Matter issue #36 about Circular Cities.