Between Social Boundaries and Planetary Boundaries

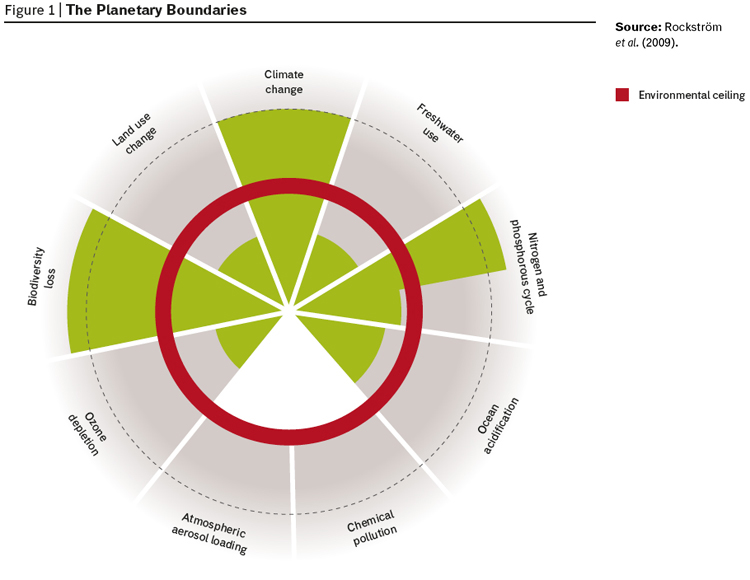

In 2009, a group of leading Earth-system scientists brought together by Johan Rockström of the Stockholm Resilience Centre put forward the concept of planetary boundaries (figure 1). They proposed a set of nine interrelated Earth System processes – such as climate regulation, the freshwater cycle, and the nitrogen cycle – that are critical for keeping the planet in the relatively stable state known as the Holocene, a state that has been so beneficial to humanity over the past 10,000 years. Under too much pressure from human activity, these processes could be pushed over biophysical thresholds – some on global scales, others on regional scales – into abrupt and even irreversible change, dangerously undermining the natural resource base on which humanity depends for well-being.

Together the nine boundaries can be depicted as forming a circle, and Rockström’s group called the area within it “a safe operating space for humanity.” Their first estimates indicated that at least three of the nine boundaries have already been crossed – for climate change, the nitrogen cycle, and biodiversity loss – and that resource pressures are moving rapidly toward the estimated global boundary for several others too (according to the latest estimates, the phosphorus cycle and the soil use – a “security” limit which has been trespassed due to deforestation – are added to the first three, Ed).

The concept of nine planetary boundaries powerfully communicates complex scientific issues to a broad audience, and it challenges traditional understandings of economy and environment. While mainstream economics treats environmental degradation as an “externality” that largely falls outside of the monetized economy, natural scientists have effectively turned that approach on its head and proposed a quantified set of resource-use boundaries within which the global economy should operate if we are to avoid critical Earth System tipping points. These boundaries are described not in monetary metrics but in natural metrics fundamental to ensuring the planet’s resilience for remaining in a Holocene-like state.

Yet even while the nuances of defining the nature and scale of boundaries are being debated, a critical part of the picture is still missing.

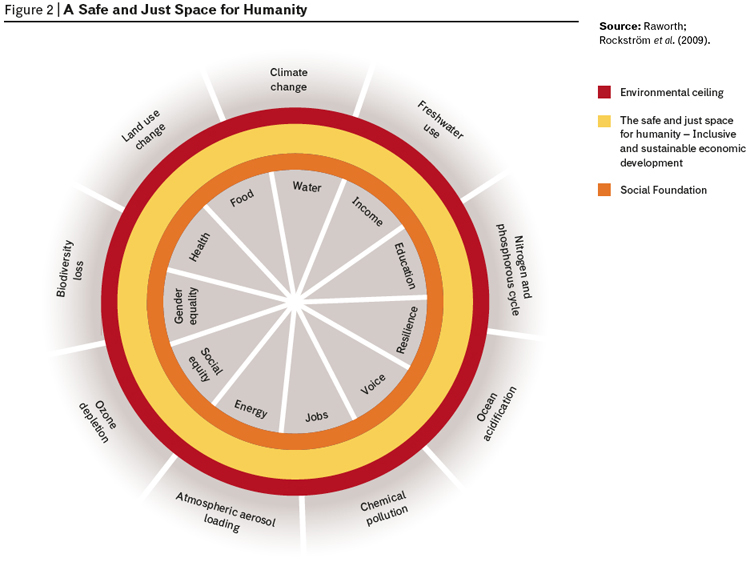

Yes, human well-being depends on keeping total resource use below critical natural thresholds, but it equally depends upon every person having a claim on the resources they need to lead a life of dignity and opportunity.

Between the social foundation of human rights and the environmental ceiling of planetary boundaries lies a space – shaped like a doughnut – that is both an environmentally safe and a socially just space for humanity (figure 2).

Combining planetary and social boundaries in this way creates a new perspective on sustainable development. Human-rights advocates have long highlighted the imperative of ensuring every person’s claim to life’s essentials, while ecological economists have emphasized the need to situate the global economy within environmental limits. This framework brings the two together, creating a space that is bounded by both human rights and environmental sustainability, while acknowledging that there are many complex and dynamic interactions across and between the multiple boundaries.

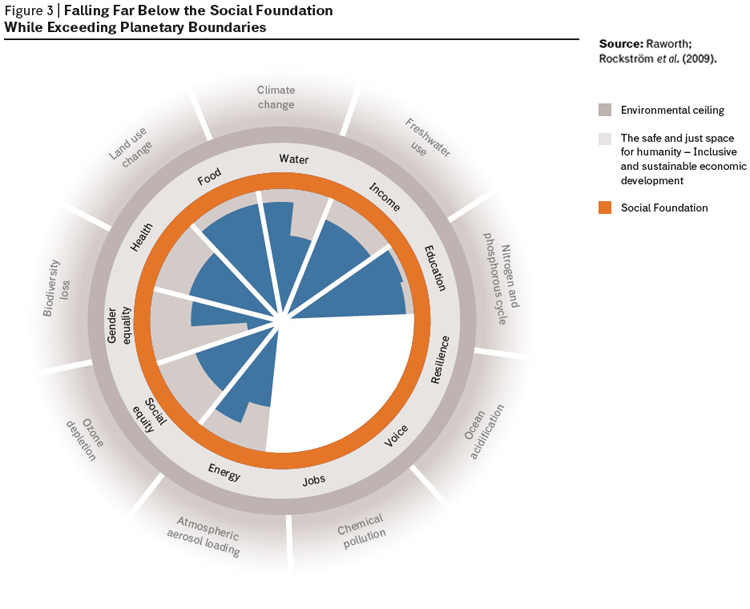

Just as Rockström and the other scientists in 2009 estimated that humanity has already transgressed at least three planetary boundaries, so too it is possible to quantify human outcomes against the social foundation. A first assessment, based on international data, indicates that humanity is falling far below the social foundation on eight dimensions for which comparable indicators are available. Around 13% of the world’s population is undernourished, for example, 19% of people have no access to electricity, and 21% live in extreme income poverty.

Quantifying social boundaries alongside planetary boundaries in this way makes plain humanity’s extraordinary situation (figure 3). Many millions of people still live in appalling deprivation, far below the social foundation. Yet collectively humanity has already transgressed several of the planetary boundaries. This is a powerful indication of just how deeply unequal and unsustainable the path of global development has been to date.

Dynamics Between the Boundaries

What, then, is the biggest source of stress on planetary boundaries today? It is the excessive consumption levels of roughly the wealthiest 10% of people in the world and the resource-intensive production patterns of companies producing the goods and services that they buy. The richest 10% of people in the world hold 57% of global income.

Cutting the resource intensity of the most affluent lifestyles is essential for both equity of and sustainability in global resource use.

What are the implications, then, of this framework of social and planetary boundaries for rethinking the metrics needed to govern economies? The overriding aim of global economic development must surely be to enable humanity to thrive in the safe and just space, ending human deprivation while keeping within safe boundaries of natural resource use locally, regionally, and globally.

Imagine if the doughnut-shaped diagram of social and planetary boundaries found its way onto the opening page of every macroeconomics textbook. So you want to be an economist? Then first, there are a few facts you should know about this planet, how it sustains us, how it responds to excessive pressure from human activity, and how that undermines our own well-being. You should also know about the human rights of its people and about the human, social, and natural resources that it will take to fulfill those. With these fundamental concepts of planetary and social boundaries in place, your task as an economist is clear and crucial: to design economic policies and regulations that help bring humanity into the safe and just space between the boundaries and that enable us all to thrive there.

Under this framing of what successful economic policymaking looks like, the metrics for assessing the journey toward sustainable and equitable development must widen significantly. In line with the recommendations of the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, at least four broad shifts are needed – and are under way – for creating a better dashboard of economic and social progress.

The first shift is from measuring just what is sold to what is provided for free too.

Second, we need to shift from a focus on the flow of goods and services to monitoring changes in underlying stocks as well.

The third shift needed is from a focus on aggregates and averages to monitoring distribution too. Many economic indicators are either aggregates (national GDP, for example) or averages (GDP per capita). But it is the actual distribution of incomes, wealth, and outcomes across a society that determines how inclusive its path of development is.

The final shift to create a better dashboard of economic and social progress is from monetary metrics to natural and social metrics too. Not everything that matters can be monetized, nor should it be. “Social metrics”, such as the number of hours of unpaid caring work provided by women and by men, and “natural metrics”, such as per capita footprint calculations for carbon, water, nitrogen, and land, must be given more visibility and weight in policy assessments.

This creation of metrics beyond GDP is crucial, but of course it brings new complexities and controversies. There is an ongoing dance (or a battle) back and forth between the metrics of economics and ecology to determine whose language, concepts, and measurements will define the emerging paradigm of development. Will economics subsume ecology, assigning a monetary value to all natural resources, complete with assumptions of shadow prices, substitutability, and market exchange? Will ecology predominate, proscribing a space for economic activity within safe boundaries designed to avoid critical natural thresholds, expressed and governed only through the evolving natural metrics of the planet? Or will it be possible to create a dashboard of indicators that incorporates the realities and insights brought by both approaches?

If such holistic metrics can be created, they must be compiled and reported in ways that empower people around the world to hold policymakers to account. This change alone would provide governments, civil society, citizens, and companies alike with a far better dashboard for navigating humanity into a safe and just space in which we all can thrive.

Note: the article is an excerpt from the chapter written by Kate Raworth for the report State of the World 2013, Worldwatch Institute, Island Press, 2013.

The Circular Economy Will Help Us

Interview with Kate Raworth by Marco Moro

The first question is about the possible role of bioeconomy and circular economy as positive factor to reconnect economy to environment and society.

Could the progress towards a bio-based economy – an economy increasingly based on a sustainable use of renewable resources – help to reach the “safe and just space for humanity”? Under which conditions?

KR: If we want to stand a chance of getting into the safe and just space of the doughnut, we’d be smart to put circular economy thinking at the heart of our economies. Circular economy is one of the most direct – and dynamic – ways of bringing economic activity back within planetary boundaries. But if we want it to help bring us over the social foundation, we also need to think about the social implications of adopting circular economy business models and government policies. What would that look like? Seeking ways to meet the health, education, energy and food needs of low income communities through circular-economy approaches; involving local communities and minority groups in design; promoting job-creating approaches, and considering the distributional consequences of the circular-economy shift.

These ideas are summed up in a briefing note I wrote for IIED in 2014: http://www.iied.org/ten-ways-secure-social-justice-green-economy.

The second question is about the possible impact of a more resource-efficient economy (a circular economy). Could the development of an effective circular economy lead to a de-growth of the economies? Less consumption, less production, less jobs... Is it a real risk? Or will a positive interpretation of that trends prevail, leading to an additional demand and stabilising the economies?

KR: If we want to see continued growth in high-income countries, then we first need to deeply rethink what we mean by growth because today’s rising GDP is in good part being generated through widening social inequalities and ecological degradation. More important than an ever-rising national income is a far better distributed national income, along with the regeneration of the social, human and natural capital on which all our wealth and wellbeing fundamentally depends. As the transition to a circular economy continues to take-off, we need to develop metrics that are fit for capturing the growth of this real wealth. Indeed, I believe that in today’s high-income countries, we have the chance to create economies in which the question of whether GDP is going up or down in any one year is no longer taken to be the critical sign of success – because we will have far richer and more relevant measures for the wellbeing that we ultimately seek.