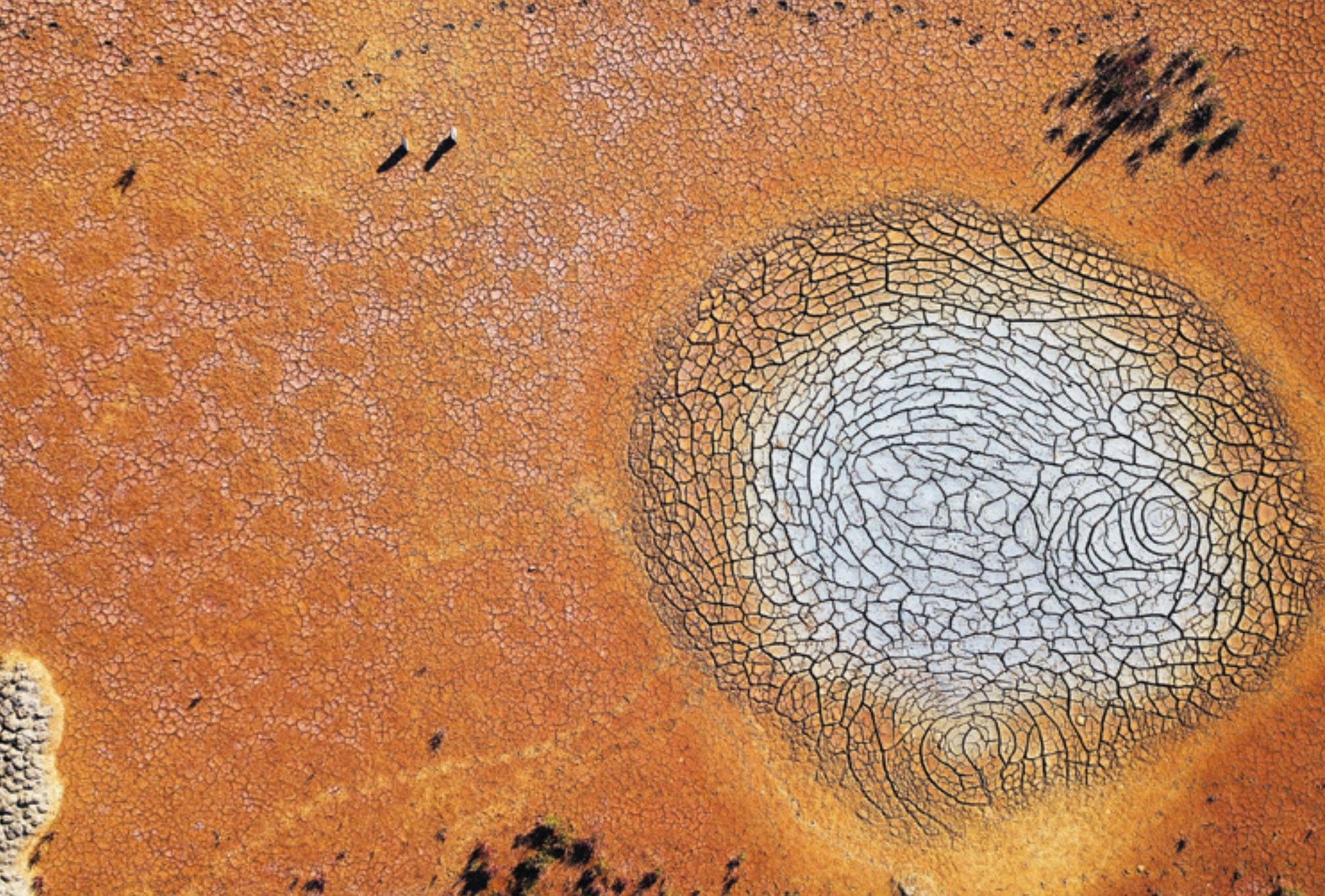

Desertification, spurred by soil exploitation and climate change, is today an increasing threat also in Europe. Measures to prevent it are not enough. A coordinated strategy is lacking, but the new Common Agricultural Policy could play a crucial role.

Aridity, drought, loss of fertility, soil unproductivity, desertification. These are concepts belonging to a semantic area that Europeans are used to identifying somewhere else, distant both in time and space: in Africa, in Central America and a different geological era. Nevertheless, today, desertification is a problem much closer to home in the Old Continent.

Intensive agriculture, deforestation, industrial pollution, mining exploitation and uncontrolled urbanization, to which we must add climate change effects, are leading several areas of Southern Europe to the brink of a soil crisis. What is worse, this is an underestimated crisis, at least by European institutions.

Defining the Problem

To talk about desertification, we must first agree on definitions. “Until a few years ago, we associated this term with the advancing deserts, as it is happening, for instance, in the Sahara and the Sahel Belt,” explains pedologist Carmelo Dazzi, President of The European Society for Soil Conservation. “Today we refer to this phenomenon as ‘desertization’, while the word ‘desertification’ has taken up the meaning of a wider problem, concerning different environments all over the globe, including the Mediterranean Basin.”

Thus, the official definition has become provided by UNCCD (United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification): “soil degradation in arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas due to several factors, including climate change and human activities.” The above-mentioned areas represent over 40% of Earth’s surface and are home to about one third of the world’s population: the fact that their capacity to sustain life is at risk is undoubtedly a huge problem.

How big the risk is and what the threshold is beyond which soil loses its productive capacity is another question that must be agreed upon. Soil typologies can be classified according to their aridity value indexes. That adopted by UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) defines the aridity of an area as the ratio between mean annual precipitation (P) and mean potential evapotranspiration (ETP). The desertification process presents three critical thresholds that mark the begging of sudden transformations: once the 0.5 aridity value index has been exceeded, the soil is affected by a loss of fertility acceleration; when it reaches 0.7 it loses structure and is vulnerable to erosion; beyond 0.8 the system collapses, plants are no longer able to grow and the area becomes a desert. According to a recent study published in Science, 20% of Earth’s surface will exceed at least one of these three critical thresholds by 2100.

As far as the damage already caused, the extension of degraded lands is uncertain: United Nation’s estimate varies from one to six billion hectares. The reason for such a wide gap is due to measuring difficulties. “Land degradation is caused by a combination of factors such as wind and water erosion, salinization due to non-sustainable agricultural practices, or soil consumption and sealing, a critical factor in Europe,” explains Pandi Zdruli, Ciheam researcher in Bari, one of the authors of World Atlas of Desertification. “Thus, mapping requires that each factor is monitored separately and then included in aggregate maps. To do this, we must combine remote survey technologies with field checks.”

According to a United Nations’ estimate, already degraded areas and areas interested by desertification are putting at risk the livelihood of over a billion people in about one hundred countries, with the ensuing (and imaginable) plethora of domino effects such as food insecurity, economic loses, migrations and conflicts. This is why soil desertification combat has become one of the Objective of sustainable development (point 3 of SDG n. 15 to be precise) and Agenda 2030 includes the achievement of land degradation neutrality, that is “a condition in which the quantity and quality of soil resources needed to support ecosystems and to guarantee food security remain stable or improve over time.” So far, 120 Countries have committed, including those of the European Union.

What happens in Europe

“Desertification in Europe is advancing inexorably. The risk is particularly serious in Southern Portugal, in some areas in Spain, in Southern Italy, in South-East Greece, in Malta, in Cyprus and areas bordering the Black Sea in Bulgaria and Rumania. Some studies have indicated that these areas often present erosion, salinization, loss of organic carbon in soil and biodiversity and landslides.” This report does not come from an environmentalist association, but from the European Court of Auditors that at the end of 2018 published a special report with a rather explicit title, “Combating desertification in the EU, faced with an increasing threat measures must be strengthened.” This equals to “we are not doing enough”.

After 2000, the European Environment Agency started a monitoring project of this problem, DISMED, Desertification Information System for the Mediterranean. Data collected till 2008 estimated the existence of areas with high sensitivity to desertification in 14 European countries, amounting to a total surface of 234,000 Km2. A decade or so later, in 2017, these data were updated and the situation, as we can read in Rachele Rossi’s report (Research Service of the European Parliament) had worsened. Areas considered at high or very high risk amount to 400,000 km2, with a hotspot in Spain (240,000 km2, practically half of the national territory) and an extension of sensible areas in Greece, Bulgaria, Italy, Rumania and Portugal.

There are multiple causes, but already landscape configuration makes the Mediterranean area particularly susceptible. “The region is characterized by frail soil, often slopping, so that it is naturally prone to degradation,” explains Professor Zdruli. “But of course, anthropic causes such as deforestation, overgrazing, forest fires and urbanization increase the risk substantially.” And then there is climate. “Scenarios concerning climate change point to increasing vulnerability, over the century, to desertification in the EU, as increasing temperatures, drought and decreasing precipitation in Southern Europe,” writes the European Court of Auditors. “Intensification of dry spells followed by more violent rainfalls can only worsen the situation,” adds Francesco Sottile (Slow Food Italy). “An area already distressed by drought, cannot absorb more than 50 mm of rain falling in just a few hours. Moreover, violent precipitation contributes to erosion, washing away the most fertile superficial stratum of soil.” Besides, there is a reciprocal and detrimental relationship between desertification and climate: the higher the temperature, the higher land degradation and vegetation thin out; soil loses its capacity to store atmospheric CO2 and its mitigation function in global warming. In other words, a vicious circle.

Agriculture’s Share

Agriculture has many responsibilities in this situation. “Non-sustainable practices such as irrigation with low quality water causing land salinization, chemical fertilizer and antibiotic abuse, the presence of plastics can only worsen land degradation,” continues Zdruli. If we normally carry out battles for more sustainable practices regarding pesticides and other chemical aids, the mechanical side of agricultural practices could be even more damaging as far as desertification is concerned. Ploughing, for instance, is a particularly invasive method, as Francesco Sottile explains, “because it buries the soil’s most fertile stratum while surfacing the least fertile.” Then there is the problem of soil compaction mainly caused by agricultural machinery. Soil is practically compressed, forming under the surface a compacted layer that does not let water through, neither up nor down, blocks root penetration and can cause water stagnation in case of heavy rainfalls.”

“All of these are practices adopted in industrial agriculture using chemicals, so they are not much concerned with preserving soil fertility” points out Sottile. “We, at Slow Food, call it our land grabbing: exploiting soil to the maximum without worrying about future generations who will inherit it and will have to cultivate it.”

An Irreversible Process?

“Soil is a crypto-resource, a resource that cannot be seen. Besides food, it provides a series of precious services such as water purification, climate regulation, contaminants reduction, nutrients cycling. And yet – Carmelo Dazzi complains – besides insiders, no one worries about its health and preservation.” To start considering soil, as we are doing, a hardly renewable resource (to form a 10 cm stratum 2000 years are needed) might help taking its protection seriously. Starting from agricultural practices. “We must implement practices such as crop rotation, organic farming, minimum or no tillage, climate-smart agriculture,” points out Zdruli. “But to be applied, farmers must be supported by a policy framework at several levels.” “A radical shift towards conservative agriculture is needed,” says Damiano Di Simine (Legambiente). “The ‘Change Agriculture’ campaign that we promote with other associations and European NGOs aims at this and influencing the Common Agricultural Policy.” Without a true European strategy for soil protection – permanently withdrawn, after several missed occasions, in 2014 – efforts are now concentrated on CAP to prevent degradation and desertification. Hoping that one of the most important Community policies (alone absorbing more than 40% of European funds) incorporates the climate and environmental challenge, already a priority for the future.

But as far as desertification processes are concerned, we have already reached a critical threshold, so is it possible to go back? “Irreversibility is relative, it depends on what time perspective we adopt,” observes Di Simine. “The Sahara was once green, Po Valley’s morainic areas at the end of the last ice age were rocky deserts. Processes can be reversible, but it might take thousands of years. And we must get to our next supper...”

Learn more about soil: download and read Renewable Matter #31