Previously published in Swiss ECS, NZZ-Verlagsbeilage, 18 September 2017 (www.swissecs.ch/de/medien-kontakt/medienecho)

The circular economy offers transformative mitigation opportunities to tackle energy and material efficiency in parallel. It addresses the root causes rather than the symptoms of climate change, and will significantly alter the way we think about and work with materials, products, services, and waste, so that we not only meet but exceed our current mitigation commitments.

The past few months have seen a number of developments that set off alarm bells and further mobilised the global community in the fight against climate change. In March, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) released a report forecasting that there would be more plastic than fish in the world’s oceans by 2050 under a business-as-usual scenario. Later in June, president Trump announced his intention to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement, despite the international community’s best diplomatic efforts to prevent him from doing so.

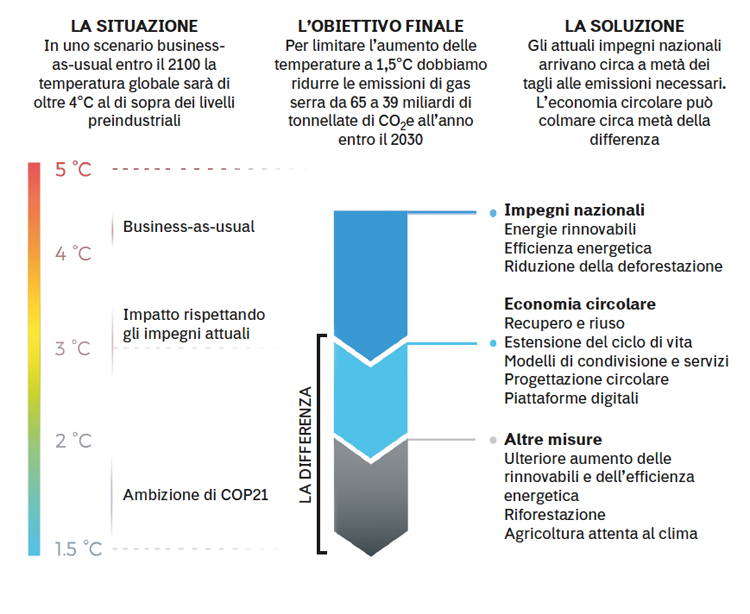

Both developments are deeply embedded in the fabric of our linear economy. Our “take-make-waste” culture continues to generate unfathomable quantities of waste, and our addiction to fossil fuels is incompatible with the aspirations of the 194 countries that have signed on the dotted line. And while citizens, businesses, cities, and countries are all taking increasingly bold action to combat climate change, current commitments are still not enough to meet the 2 °C, let alone the 1.5 °C targets we have set for ourselves.

The link between plastic waste and the Paris Agreement does not stop there either: plastics, and more broadly the materials we use, are intricately linked to greenhouse gas emissions. As Jelmer Hoogzaad explains, “as we continue to rely on fossil fuels to extract, process, and transport materials, as well as to deliver, consume, and dispose of products, ineffective material management ultimately accounts for as much as two thirds of global emissions.” It’s become clear that pledges to incrementally reduce the emissions of our industrial systems are no longer enough, and that the climate mitigation community needs innovative and systemic solutions to bolster its efforts. This is where the circular economy comes in.

Defined by EMF as “an industrial system that is regenerative and restorative by design, rethinks products and services to design out waste and negative impacts, and builds economic, social and natural capital,” the circular economy calls for a paradigm shift. Its adoption relies on both material and systemic approaches, captured in Circle Economy’s “7 key elements of the circular economy:” prioritising regenerative resources (including renewable energy), preserving and extending what is already made, using waste as a resource, rethinking business models, designing for the future, collaborating to create joint value, and incorporating digital technology.

Applying these principles to our economies opens up additional and innovative mitigation opportunities that step away from traditional efforts – such as renewables and energy efficiency – and prioritise the use of low carbon materials, dematerialisation, and system change. Using wood instead of concrete in large scale structures, for example, effectively transforms carbon sources into carbon sinks. Similarly, developing digitally-enabled product-service systems considerably reduces the need for physical assets, and in doing so positively impacts mitigation. Perhaps more importantly, the circular economy calls for us to rethink the functional needs of our society – from mobility and shelter, all the way to energy – and enables us to design a system that delivers these services more effectively.

Tapping into the circular economy’s climate change mitigation potential, however, requires for key levers to be activated in climate policy, negotiations, and finance.

For instance, while emissions are currently accounted for on sectoral and national levels, the circular economy promises to deliver cross-sector and cross-border mitigation by improving efficiency across value chains (e.g. through cooperation) and allowing for synergies across industries (e.g. industrial symbiosis). As such, it is key for policymakers and negotiators to recognise the need for these new mitigation options and to support and enable them with adequate policies and implementation frameworks such as consumption-based accounting.

As the circular economy concept matures and implementation efforts multiply, pioneering initiatives and organisations also need high-risk catalytic capital to push the circular snowball down the hill. National and multilateral development banks should therefore scrutinise their investment portfolios to understand how they have supported circular initiatives in the past, and how projects they support relate to climate finance. Such analyses will enable us to better understand the adequacy of existing financial instruments to support the circular economy’s scale-up, and to develop new ones as needed.

The circular economy is here to stay. Now is the time to make it a driving force for the ambitious climate action we need!

Circle Economy, www.circle-economy.com

Report Ellen MacArthur Foundation, The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics, tinyurl.com/znkjp7j

Circle Economys’ Seven Key Elements of the Circular Economy, tinyurl.com/y8ngqfvo