Not all plastics are indestructible. In fact, over the years, due to the constant inaction by the Countries, plastics are liable to end up not only at sea – thus making up the above-mentioned ill-famed “islands” – but also in our food chain.

As a result of their amazing success, plastics – which are easily processable but at the same time strong and durable – are increasingly present in our everyday life. However, the failure to prevent the plastic products from being dumped in the rivers and then at sea has determined a real environmental emergency, which is becoming more and more serious and must be addressed in a timely manner. This paper focuses on the so-called marine litter, which refers to the pollution of seas and oceans caused by anthropogenic waste. Although it is a major phenomenon, it has been investigated from a scientific point of view only recently.

Nowadays, various scientists – including the production system and the institutions – are looking for possible solutions to the presence of plastics in the Mediterranean marine environment and the resulting pollution effects, assessing the possible mitigation actions and the sustainable use of innovative biodegradable materials. In this regard, an important discussion-oriented event called Plastic Day was held on 8 March at the University of Siena: the debate involved the researchers from the Department of Physical Sciences, Earth and Environment of the University of Siena in cooperation with numerous institutional players both at regional and national scale, stakeholders, researchers and academics.

The marine litter actually includes any solid, durable and artificial material dumped at sea. These objects have been released to the environment voluntarily, recklessly (fishing, maritime transport, dispersion of materials and activities on the coasts), or sometimes even accidentally (shipwrecks, calamities, storms, etc.) Therefore, beyond plastics, there are also rubber, paper, metal, wood, glass, fabrics and much more. These materials often float on the sea surface and are carried towards the shoreline, in other cases, they sink to the seabed, always with possible negative effects. Moreover, some of these materials tend to degrade and become increasingly smaller over time due to the action of natural agents, such as light, bacteria, friction, oxidation and erosion.

Unfortunately, the materials made of plastics and synthetic rubber are extremely hard to die. Actually, they never die, but rather tend to cluster and form a disgusting waste mixture more or less compact, sometimes referred to as “Trash Islands”.

Unfortunately, the materials made of plastics and synthetic rubber are extremely hard to die. Actually, they never die, but rather tend to cluster and form a disgusting waste mixture more or less compact, sometimes referred to as “Trash Islands”. In these areas, the concentration of waste may include up to 25,000-100,000 objects per square kilometre, which occasionally sink to the seabed also as a result of the growth of microorganisms such as seaweeds, sponges and mussels on the water surface. Furthermore, a worse phenomenon may occur: due to the physical action of the sea and the shoreline, these plastic objects can break into “microplastics”, i.e. very small particles (less than five millimetres) which are eaten especially by the so-called filter-feeding animals and, directly or indirectly, by fish, reptiles, mammals and seabirds.

This matter of concern involves not only the oceans – where over time the sea currents have led to the formation of five large trash islands made of plastic waste (in the proximity of the northern and southern Pacific Ocean, northern and southern Atlantic Ocean, and between Australia and India.) After all, according to recent UN estimates, of the overall 280 million tons of plastics produced each year, as many as 20 million tons steadily end up at sea.

Unfortunately, the Mediterranean and the other Italian seas must face the same problems. The results of the analysis carried out by the biologists and researchers of ISPRA (the Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research), the regional ARPA offices (the Italian Regional Environmental Protection Agency) and CNR (the Italian National Research Council), also within European research programs, are already alarming. According to a recent study performed by Legambiente within the framework of the Goletta Verde campaign, plastics account for 95% of the global amount of floating waste: especially plastic paddings (39%) and bags, either entire or fragmented (17%.) The sea characterised by the highest amount of floating waste is the central Tyrrhenian Sea, with up to 51 waste units per square kilometre (the average units are 32.) In particular, the most affected areas are located in front of the coast between Mondragone (Caserta) and Acciaroli (Salerno), featuring 75 waste units per square kilometre. Generally, 54% of the waste probably has a municipal and urban origin, while 32% is connected with manufacturing or industrial activities.

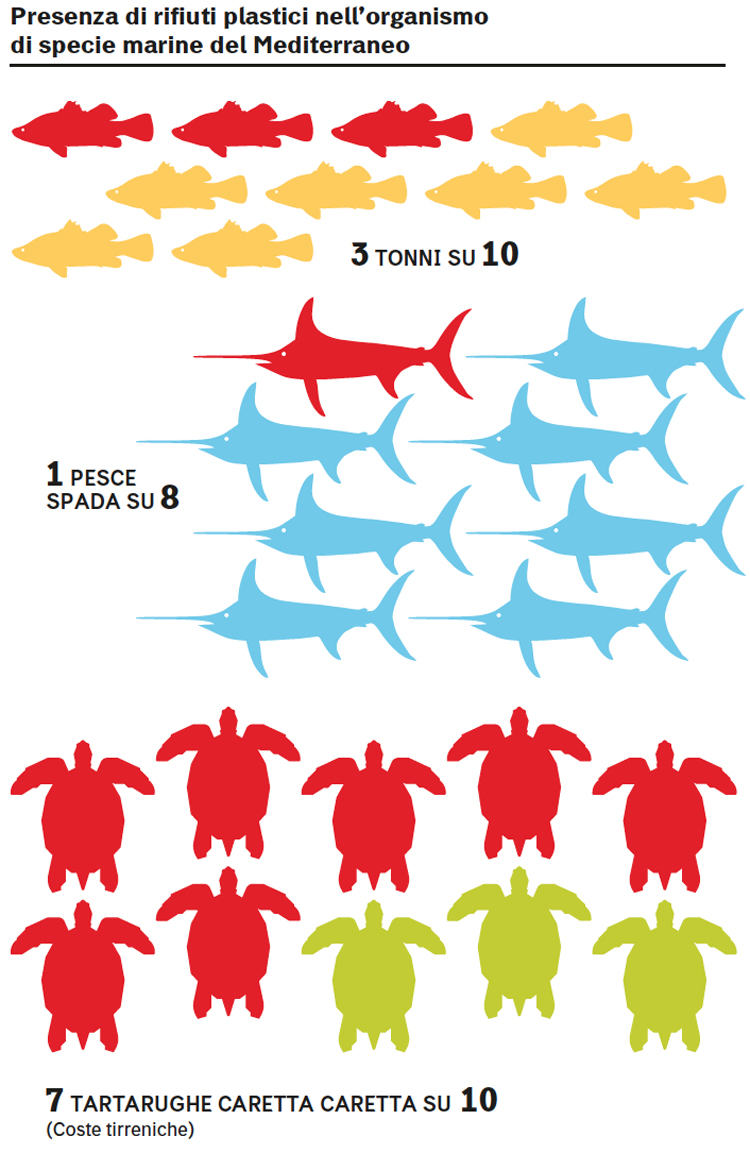

As Maria Cristina Fossi, ecotoxicologist of the University of Siena, explained during the debate “Some plastic waste has been found in three tunas out of ten and one swordfish out of eight in various Mediterranean areas.” This assumption is supported by a study carried out by the Tuscan university in cooperation with the ISPRA, which shows that the Italian seas “Nowadays feature the same large concentrations of microplastics detected in the oceans.” Obviously, this environmental issue threatens the biodiversity and the survival of various pelagic species ranging from whales to Caretta caretta sea turtles (some plastics have been found in the stomach of 70% of the specimen living near the Tyrrhenian shoreline.)

However, the negative effects on health and the productive fabric should not be neglected: waste, in fact, impairs the fishing activity, the purifiers and other production facilities, but it is also worth stressing that what is eaten by the fish ends up on our tables. In fact, the fish cannot distinguish the plastic fragments from the plankton, which is their typical food. In this way, plastics become part of the food chain and are present in great quantities in large predators: tunas, swordfishes and sharks. “Plastics not only endanger or even kill animals like turtles, but also release pollutants, such as the phthalates, which impact at various levels on the health of the marine organisms,” Maria Cristina Fossi stresses.

Therefore, according to all the experts who gathered in Siena, it is of utmost importance to find a solution to this problem. However, the issue is quite complicated and includes multiple interventions, because the waste moves from one coast to another, covering thousands of kilometres and thus requiring supranational measures, moreover the production activities which dump their waste at sea are numerous.

Obviously, the first essential step in this regard is to increase the awareness of this phenomenon, thus changing every habit more or less decisive and fostering in any case the reduction of the use of those materials which are likely to become marine litter. For example, according to various estimates, only approx. 20% of the waste is generated by maritime activities, however the procedures for the disposal of the fishing equipment – which is correctly carried out on land – should be improved. Conversely, as for the reduction of the use of plastics, it is worth focusing on those mechanisms able to increase the producer liability (i.e. by changing the packaging composition and supporting the return and recycling of the containers.) In short, special efforts are required to reduce the amount of waste, finally adopting the innovative circular economy approach, which provides for an increase in the separate collection in order to minimize the amount of waste dumped at sea. A possible solution would be an organized and systematic recovery of the marine litter, on the shorelines and offshore, through the development of collection systems intended for both the floating plastics and the waste sunk to the seabed.

There could be another solution [...]: we could pin our hopes on the production of bioplastics made of biopolymers, which tend to readily biodegrade. In Italy, Novamont especially focuses on this innovative technology. The company has invented Mater-Bi, a family of biodegradable plastics involved in the production of plastic bags as well of the nets used in the mussel farming sector. However, as highlighted by Francesco Degli Innocenti, Ecology of Products and Environmental Communication Manager of Novamont, “It should be stressed that the bioplastics industry does not regard biodegradability as a “license to litter.” All the products, in fact, should be designed to be recovered somehow. The biodegradability helps the organic recycling, which may turn out to be very useful in many cases.” According to Degli Innocenti, the biodegradability at sea is a crucial property for the items which are likely to be accidentally released. In these cases, the biodegradability can contribute to the reduction of the environmental risk. “The plastics dumped at sea can be ingested by the animals with consequent damages” as stressed by Degli Innocenti. “The risk of this potential damage can be reduced by means of a lower concentration of plastics in the water and a lower residence time. In this way, the risk is significantly reduced, even if not fully prevented. Our tests, validated by Certiquality within the “Environmental Technology Verification” EC pilot programme, show that the innovative Mater-Bi bioplastics biodegrade in less than one year.”

It is easy to imagine the astonishment of the scientific world at the publication last November of a UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) report entitled Biodegradable Plastics and Marine Litter. Misconceptions, concerns and impacts on marine environments. Globally it did not regard degradable bioplastics as a solution to the problem, considering that the biodegradation of the polymers would occur only under specific industrial conditions, and not in the maritime environment, where they would probably act like ordinary plastics. “The spread of biodegradable products – according to the UNEP report – is going to significantly reduce neither the amount of plastics released into the oceans nor the physical and chemical risks to the maritime environment.” Conversely, as stressed by the UN agency, the “biodegradable” label would paradoxically urge the people to produce and release the waste into the environment.

The Open-Bio research consortium, a project funded by the European Commission to support the standardization, labelling and procurement of bio-based (renewable) products, has a different opinion on this matter. In a recent paper drawn up in response to the UNEP report, Open-Bio strongly emphasizes the key role played by the prevention of littering and the development of a proper waste management plan (including the biodegradable products.) Thus the initiatives to be implemented to tackle with the waste production include prevention, training and an adequate waste management (such as the enforcement of separate collection and organic recycling of biodegradable plastics.) Therefore, in contrast to the assumptions of the UNEP, the truly biodegradable plastics can be decisive for the maritime environmental protection, as they are also involved in the production of professional products such as fishing, fish farming and beach equipment, which are likely to be dispersed.

This topic is a subject of major interest not only in Europe: recently, in fact, the ASTM (American Society for Testing Materials) and the ISO (International Organisation for Standardisation) have published new testing methods intended for the assessment of the biodegradation at sea.

In conclusion, the marine litter has been put on the full environmental agenda containing all the issues which should be faced at global scale, considering that – as evidenced by the conference held in Siena – the plastic waste moves from one continent to another in an impressive way.

Plastic Day: Marine litter, effects, mitigation and sustainable solutions, University of Siena; www.unisi.it/plastic-day

UNEP, Biodegradable Plastics and Marine Litter. Misconceptions, concerns and impacts on marine environments; tinyurl.com/zzdabof

Open-Bio research consortium, www.biobasedeconomy.eu/research/open-bio/

Top image: ©Freevector – Graphic elaboration