In recent years, the circular economy has drawn increasing attention, so much so that today it has become a sort of slogan/symbol to describe environmentally-friendly changes made (or to make) to a product.

The debate at EU level – and the ensuing deadline of 28th August regarding public consultation – led businesses, associations, consortia and European and non-European public administrations to discuss the kind of approach to adopt. And the ways in which different types of products/waste should be considered as far as recovery and recycling are concerned.

Beyond this heated and open political debate, that by the end of the year should lead to an EU Commission guidance document, we still must contextualize the adopted measures with means able to monitor the introduced actions and their achieved and achievable results.

This can only be done through checks at different levels – from single companies to EU level – and using instruments and methods able to “measure” the real action undertaken to increase a product’s circularity. Otherwise, we run the risk of starting political and environmental actions in the field of the circular economy without clear objectives and without the guarantee that this is the most effective way to safeguard natural resources and to start a real market of recycled materials.

Focussing our attention on how to quantify or measure a product’s circularity, this issue must take into account – albeit being delicate and complex – a series of aspects including:

- the use of sole indicators on the mass flow of materials to achieve a single result, measurable and comparable amongst different types of products;

- the differentiation of resource types used: raw materials from renewable and non-renewable sources, recycled and permanent recycled materials;

- the determination of a time limit within which a material can be defined as coming from a renewable source;

- social aspects of the supply chain;

- the active involvement of consumers in choosing to buy a virtuous product through simple and clear communication.

Following the circular economy’s basic principles – in a nutshell, the safeguard of natural resources and the maximum exploitation of used materials through re-using and recycling – we must now define how to assess and measure actions and their results.

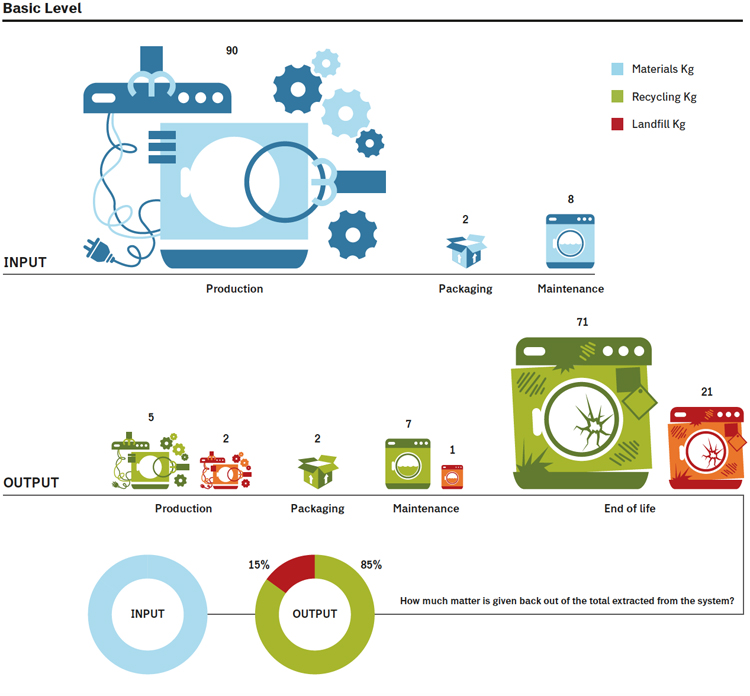

A viable solution could be to carry out a mass balance (material balance) to quantify the input and the output in terms of resources characterizing a product’s life cycle. It means measuring the quantity of material (Kg) extracted to make a product compared to the quantity (kg) given back when such product reaches the end of its life cycle. Taking into account also complementary material resources used for transportation, use and maintenance (for example for packaging).

The difference between inputs and outputs of resources enables us to calculate a material balance for the circularity of a product: the closer the quantities of output material recovered and recycled are to the input value, the higher the product’s circularity. In this way, the maximum circularity of product is 100%, while its partial circularity varies from 1 to 99%.

There are different levels with which we can quantify the material balance, taking into account different parameters. As an example, they include:

- Basic Level: mere quantification of used resources;

- Intermediate Level: quantification of used resources divided by types of materials;

- In-depth Level: quantification of resources used divided both by types of materials and origin: from renewable and non-renewable sources, recycled and permanent recycled materials.

These three levels of measuring a product’s circularity enable businesses to apply a personalized balance according to the objectives to meet and sector’s requirements. For example, the in-depth level can be even more specific through the identification of certifications characterizing materials (from renewable sources and/or recycled), or biodegradable and/or compostable materials.

In other instances, companies close to the basic level can include in their material balance the division into materials from renewable and non-renewable sources. Such approach flexibility surely encourages the spread of this method, while leaving to businesses the possibility of defining the level of analysis/improvement to advance.

Companies without an end-of-life management policy clearly present the most difficult criticalities in assessing a product’s circularity. In this case, they must understand which strategy to adopt in order to avoid their products to have 0% circularity.

Those companies that already participate in collection and recovery systems of their products through chain consortia or those that have autonomous recovery systems do have an advantage. This is a revival opportunity for chain consortia since they manage and hold products’ output data.

The results achieved using one of the three levels of measuring a product’s circularity can become a means of communicating with the market. Particularly, with consumers, for example using a label highlighting a product’s circularity and the choices made by a company.

Moreover, the application of this calculation method to a series of companies within a certain area could encourage aggregation and lead to economy-of-scale results, from municipal to national level.

The circular economy can become an action strategy useful in safeguarding natural resources only if applications are able to measure the real performance of a product and take into account the real abilities of a company to undertake monitoring and improving actions.

Italy, like many other countries whose production panorama is characterized by small and medium enterprises, cannot hope to achieve useful results without actively involving such companies. First and foremost, a gradual and above all voluntary approach is needed.

Info