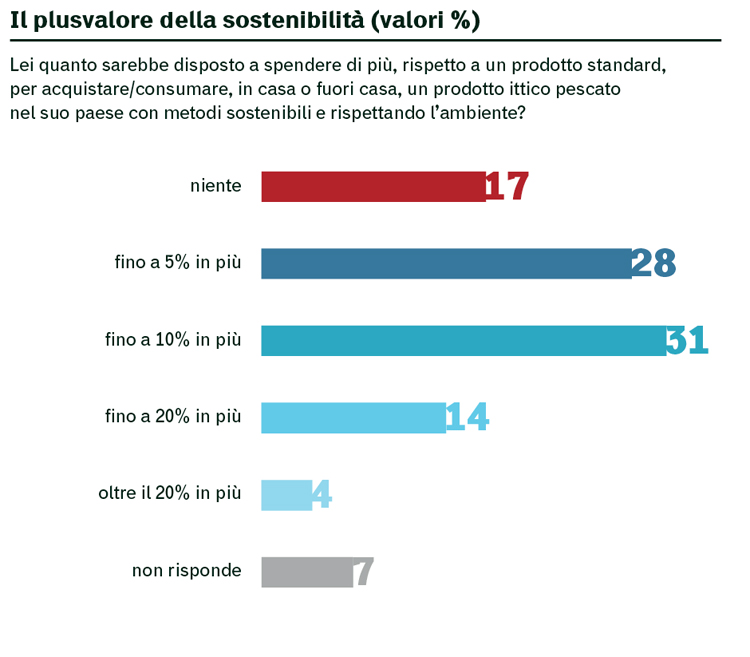

We eat fish at least once a week. We buy it mainly from the supermarket and we are willing to pay more providing it is from the Mediterranean, fished with sustainable methods and respecting the environment. However, according to a survey carried out for Greenpeace by Ixé, few Italian, Spanish, and Greek consumers know the new labelling regulations that, in order to permit consumers to make a more informed choice, imposes the obligation to indicate both the origin of the fish and the fishing equipment used.

While, on the one hand, fishing is one of the oldest pursuits known to mankind, and it continues to guarantee livelihood to 12% of the world’s populations, its sustainability is a relatively young concept. Over the past 50 years, the world’s demand for fish has almost doubled and, in order to satisfy a continuously increasing need, national governments are supporting mostly industrial fishing with public funds. But still, small-scale traditional fishing, carried out on crafts which are less than 12 metres in length and do not use towed equipment, makes up 80% of the fishing vessels currently operating across the world and guaranteeing millions of families work and sustenance.

This is a type of sustainable fishing. It has less impact on the marine habitat and respects the biological rhythms of the sea, allowing fish to reproduce and develop. A sustainable fisher respects the rules, uses only equipment which is permitted and operates in authorised areas and periods. This type of fishing can guarantee a future for the Mediterranean and the 300,000 fishers operating in it.

Fourteen years ago, on 23 December 2003, European Union ministers, meeting in Venice, sealed a deal with the south shore of the Mediterranean to create protection zones for conservation, fishing control and combating illegal fishing. That was another era. There were more than 200,000 fishers and over 80,000 fishing vessels, while these days the figures are almost half the aforesaid. So new rules were established to protect highly-migratory species like tuna, swordfish, sardines and anchovies. We must now take another step towards balanced, profitable, sustainable harvesting and afford greater attention to small-scale fishers.

These were the matters discussed in Malta on 30 March 2017 at the Ministerial conference on the sustainability of Mediterranean fisheries. Directed by the EU’s Commissioner for the Environment, Karmenu Vella, ministers from eight European countries (Spain, France, Italy, Malta, Slovenia, Croatia, Greece and Cyprus) and seven non-EU countries (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Turkey, Albania and Montenegro) representing 80% of the fleets, signed a new declaration, the “Malta MedFish4Ever:” a political project and a timetable covering the coming 10 years whose objective is better control of the seas and sustainable management of fisheries in the Mediterranean. Some of the commitments made were: combating illegal fishing, developing protected marine areas (up to at least 10% of the Mediterranean basin by 2020), devising a plan for small-scale fisheries by 2018, promoting industries which practice selective, low environmental-impact fishing and systematic, standardised data collection regarding fish stock.

Until now the Mediterranean situation has been dealt with through the adoption of certain legislative measures, which provide for, among other things, limits to the fishing effort, regulating minimum catch sizes and fishing equipment use methods. In any case, these measures are not sufficient because there is no ecosystemic approach to justify it and a global policy for them to be inserted in. Furthermore, other complementary but not less important measures which guarantee fishing diversification are needed. One of these is the promotion of sustainable fishing tourism and awareness campaigns directed at consumers who, through their food choices, can contribute to improving the state of the Mediterranean by, for example, favouring the consumption of local fish species, which are often neglected by wholesale and little known but by no means less good.

We must not forget the protected marine areas, that are not just a tool for protecting the environment, but also a way of managing fishing that has the benefit of being ecosystemic by definition. Finally, fishers and their communities must be involved in the decision-making process as they are an integral part of the solution, because they are the ones experiencing the sea every day. Their contribution, just like that of all the other involved parties, from scientists to non-governmental organisations, is an opportunity which policy should take advantage of. The effectiveness of our actions now depends on our degree of cohesion, coordination and collaboration with international bodies which manage fisheries. Finally, we must consider that fishing depends on the health of the stock, but the health of the stock, in turn, depends on the quality of the sea. That is why Europe is working on drawing up an ocean governance plan which is both multidisciplinary and international.

“Poorly-informed fish consumers” Survey, tinyurl.com/yazgbv27

Greenpeace, Fish consumption habits in Italy, Report 2016; tinyurl.com/y96dz7oz

Malta MedFish4Ever Declaration, tinyurl.com/y8zf22ku

#MedFish4Ever campaign, tinyurl.com/ycfh6b5t