Terms such as “biobased, sustainable, circular materials” are at long last starting to be part of the layman’s vocabulary. Indeed, characterizing an object by its material is a leverage attracting more and more consumers.

After all, dealing with materials making up objects we use on a daily basis and being able to describe them in the most appropriate way is key both as a business opportunity and to manage raw materials in a more sustainable manner. Materials determine durability, likeability and performance of products; once their use is over, the matter they are made of is the only thing left behind. The choice and knowledge of the material are essential to establish an object’s environmental impact already in the design phase, which is why more and more designers are attracted to this issue.

Material Tinkering: a first approach in University laboratories

In several Italian and European universities of Product Design the experimental approach is becoming an increasingly popular methodology in the teaching of materials.

While in the past teaching was mainly focused on the knowledge of existing materials, today a few professors started to deal with the theme with an experiential approach, guiding students in the creation of a new material through a method leading to “get one’s hands dirty.” Students, with a scientific and technical approach, are encouraged to ponder over the environmental consequences of their choices during the design phase, over sensoriality and the emotional meaning some objects may take up with various materials.

Carlo Santulli, professor of Science and Technology of Materials at the School of Architecture and Design at UNICAM University in Camerino, sums up in his courses two ways with which students related to the theme of materials: in the course “Performance and conforming characteristics of materials” students are guided in the selection of the material for the production of a design product, while in the course “Experimentation of Innovative Materials for Design,” students are spurred to explore matter in search of new viable solutions. The latter is characterized by a workshop approach focused on the creation of bioplastics and other materials through the use of waste materials (possibly locally sourced) and recognizable by students thanks to their working or personal experience. The enthusiasm and familiarity with the material help students build its “personality,” by conceiving a path and tests enabling them to obtain expressive and technical characteristics and eventually perhaps product application. “In order to include them in a credible project narrative – states Santulli – I elicit help from other teachers and professional designers who, thanks to their experience, can better envisage possible use destinations, thus avoiding easy solutions and enhancing aesthetic qualities or used organic materials from the beginning.”

In addition, connected to the creation of DIY materials, the “Designing Materials Experiences” course led by Valentina Rognoli, Stefano Parisi and Camilo Ayala Garcia at the Milan Polytechnic, Design School, aims at developing a matter concept, a material self-produced through a low-tech approach.

Students carry out Material Tinkering, thinking through the senses, building a thorough know-how ranging from technical-physical knowledge of the material to a sensory-expressive and experiential dimension. The method also includes studies on users and the ability to envisage application scenarios.

According to Valentina Rognoli, a change of paradigm is taking place whereby designers self-produce proposals “already incorporating users’ desires and needs; often these are innovative from the point of view of properties, sustainability, resources and processes” and can in turn inspire the development of further materials.

At NABA, the New Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, the course “Materials and New Technologies for the Innovation of Projects,” follows the same multi-cultural context of the Milan Polytechnic. Students are encouraged to research new materials starting from organic substances, preferably discarded ones or from self-generating substances such as mushrooms, algae or bacteria. The course focuses from the very start on an approach of environmental sustainability and reduction of impacts and identifies, in the very concept of sustainability, a key factor for innovation.

|

|

Bacterial cellulose

|

|

|

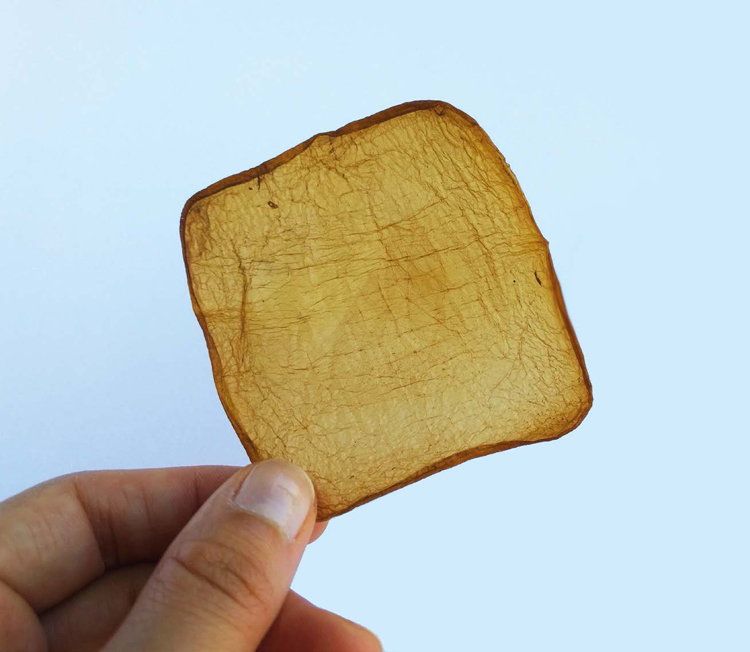

RC+L, material obtained using coffee dregs and made by students Matteo Brasili, Elisa Castelletta, Giovanni Dipilato, Gaia Ravera, Martina Sacco, Dario Javier Sosio during the course “Materials and new technologies for design innovation” at NABA

|

At the end of the course, students must give a final presentation during which professionals linked to the world of materials and design are invited. Students present and discuss their achievements: an exchange enriching everyone that goes beyond individual education.

Besides six-month courses, a few universities offer training solutions highly specialized on the theme of materials. “Design through New Materials” is a case in point, led by Elisava Barcelona School of Design and Engineering. According to the course director Laura Clèries “it is important to be able to think through manual skills. Besides being a creative resource, the attention towards materials take up a protagonist role in the design process; in the case of our Master’s, a scientific and creative approach is linked to a multidisciplinary, social, anthropological, technological and aesthetic approach.” The programme supports practical workshops, visits to industries and important innovation centres of materials. The master’s deals carefully with issues linked to intellectual property and marketing, a key theme when marketing a product, or to recognize the potential of new business models associated with materials.

From prototype products to mass production

The students’ enthusiasm in experimenting with DIY materials deserves more than one explanation: deep-seated historical reasons represented by changes that people brought to their territories and times and more recent cultures such as the maker movement and the democratization of scientific knowledge have an influence.

Even though today we are surrounded by mainly industrial objects, the pleasure of the artisan know-how still answers, in the oldest part of our brains, the need of improving our status, highlighting an aspect of emotional design, in the designers in the first place. For material tinkering activities, hands, tactility are key tools together with other senses. Thai artist Nithikul Nimkulrat, teacher at the Estonian Academy of Art, Faculty of Design (Tallin) confirms this by saying that craftsmanship is not just a way to produce things, but also a means to think through hands manipulating material.

This is the fundamental concept underpinning experimentation of DIY materials. But it is also necessary to apply both a scientific methodology for the quality of materials to achieve and applications, such as the Material Driven Design. In such designing project materials are not chosen at the end, but it coincides with the designing input, reversing the question from “with which material can I achieve my project?” to “what project can I achieve given the characteristics of the material I obtained?” This is mainly the new viewpoint that can improve the quality of matching between material and project, leading to innovative solutions.

|

|

Nithikul Nimkulrat, The black&white striped armchair, 2014. Photo credit: Nithikul Nimkulrat (www.inicreation.com)

|

A big push to the trends of DIY projects was also given by the open source movement, where a complex science such as that of materials, needing expensive laboratories and machinery, reached makers’ garages opening up to the use of low tech resources and technologies, enabling the emergence of unexpected but equally effective solutions which often stem from unpreparedness of those experimenting and the ensuing unconventional perspective. After all, in this context, as well as in the scientific discipline, mistakes are not seen in their negative aspect, but rather as a knowledge factor within an ever-changing knowledge process.

Regardless of the fact that students or designers may experiment, the outcomes of research will produce two possible results: the former – mainly aimed at the research process, coincides with the unique piece, the prototype object that intends demonstrating the material’s potential through the first prototypes and samples, the result of an art that very few alchemists know, but whose production process is already deducible. Then, if the obtained results are promising, a new scenario, that of industrial reproducibility, can open up, where mass production is standardized. Some experimentations on material go beyond the pleasure of DIY and have characteristics of innovation and sustainability for which it is worth standardizing production.

This is what happened with Tom va Soest with his dissertation project, presented to the Design Academy in Eindhoven in 2011 which focused on a matter experimentation aimed at upcycling construction materials. His objective was the recovery of materials in demolitions: once in possession of the scrap materials he crushed and processed them for two years in a garage, obtaining new and better bricks, while collaborating with a few companies in the sector. In 2013, Tom van Soest together with Ward Massa founded a start-up, naming it after the project: StoneCycling. Today, the company offers several brick collections “Waste Based Bricks” each one characterized by unique hues and textures thanks to the initial material mixes. Then in 2016, the first building constructed with such bricks was erected. But when we ask Ward Massa if, now that they created a company, research is still the main part of their activity, he replies: “Of course, we are a small organization, which compels us to think about future materials: we can exist only if we continue to innovate.”

|

|

StoneCycling. Photo credit: Dim Balsem (www.stonecycling.com)

|

|

|

Tom van Soest and Ward Massa of StoneCycling. Photo credit: Dim Balsem (www.stonecycling.com)

|

The StoneCycling is not an isolated example, because the DIY material’s trend is growing and present designers with a new opportunity: designing the very material. Since considerable innovative and sustainable research is being carried out in this direction, it seems correct to mention them in schools and, why not, to adopt material research as a teaching method for a better emotional involvement of students in the choice of materials and in understanding their potential.

This topic is becoming particularly important when we think that the choice of material needs, with a view to designing for the circular economy, an extra oomph, since often the pre-production phase (i.e. extraction and processing of raw materials) and that of processing (i.e. manufacturing of products) generate most environmental impact mainly for those products, furniture for instance, that do not need to use resources for their functioning.

Carlo Proserpio confirms this. He works in the laboratory of Design for the Environmental sustainability of the Department of Design of the Milan Polytechnic, an expert of Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Design, who highlights how all choices made during the design phase are fundamental for the emission that the product will generate during the whole of its life cycle and how the selection of materials is one such choice albeit not the only one. In particular, Proserpio recommends choosing materials not in relative terms (by pinpointing in a range of materials the most sustainable one), but considering all the characteristics that the material can bestow on the product’s whole life cycle, consulting an LCA on the product and from there defining Life Cycle Design priority strategies to adopt.

The experiential aspect linked to conceiving and manipulating new materials has now more opportunities: analysis software of life cycles, ecodesign strategies, involvement of more people in the experimentation and information exchange are effective teaching tools to create low-impact environmental impacts, while guaranteeing a sustainable use of resources.

Info

Immagine in alto: DIY bioplastics