Complexity is key to analysing employment’s social, economic and environmental challenges. This is a pivotal statement in the research and studies by Enrico Giovannini – an economist and statistician, former Minister of Labour in Italy, Chairman of ISTAT – The Italian National Institute of Statistics – and currently head of the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASviS). Giovannini has worked for ISTAT, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and as Minister of Labour; processing countless data matrices in an attempt to grasp the evolution of the labour market and find solutions to the growing crisis in employment. He has always worked to safeguard employment through the use of tools such as social safety nets, for which funds trebled during his time as minister; or with measures such as Garanzia Giovani (Youth Guarantee), aimed at supporting youth employment. As for social policies, he launched the reform of ISEE –Equivalent Economic Status Indicator used in Italy – and set up new instruments for the fight against poverty such as Support for Active Inclusion, an early form of minimum wage. Today, in his capacity as head of ASviS, he promotes the dual approach of sustainable development and fight against social exclusion. Renewable Matter interviewed him to understand the actual impact that an effective adoption of the 2030 Agenda would have on the fight for decent, well-paid and lasting employment for all.

Does labour play a pivotal role in the Agenda?

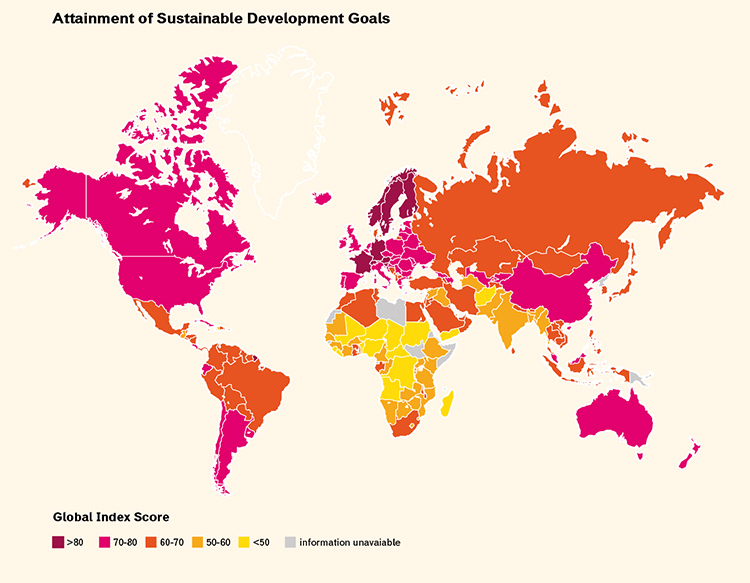

“The document clearly tackles the issue of decent employment, so much so that one of the goals is entirely devoted to it. Through good employment many more targets can be achieved, from removal of inequalities to youth integration into adult life. It goes without saying that through decent employment an adequate income is guaranteed so that one can invest in health, education and so on. The 2030 Agenda, the Global Agenda for Sustainable Development, thought out by many as a purely environmental agenda, has actually become an integrated vision of economic, social, environmental and institutional aspects. This is an extraordinary step forward from a conceptual point of view. In the schemes that I often use, where I show how the way we produce and consume impacts on ecosystems, I also included a box on social systems that, in the same way as ecosystems, produce services for people free of charge and offer lasting wellbeing. I am referring to peace, confidence in the future, and social cohesion. If these fail, then there is neither economic growth nor institutional sustainability. There is a key passage in Pope Francis’ Laudato Si,’ where he reminds us that the culture generating physical waste is the same one generating human waste: the poor, the unemployed, the marginalised. The increase of such people jeopardises social cohesion and every country’s future. And also the environment’s.”

Amidst insecurity, deregulation of the labour market and the gig economy, what does a decent job imply in 2018?

“Besides being a job that has nothing to do with slavery and its new forms, and with no physical risks inherent to it, it must be an adequately paid job. This is a key issue throughout Europe. Let’s take Italy as an example, where the number of employees is higher now compared to the employment peak before the 2008 crisis. This would seem like great news, which is in turn emphasised by some politicians.

However, if we put the amount of employment in new paid jobs in proportion to hours worked, we are about 1,3 million work units below peak. This means that new jobs are not only insecure but they do not even fulfil the income requirements of families. Moreover, we are moving towards an even more complex situation. At a global level, we should create 600 million jobs by 2030 only to keep up with the planet’s population growth, whilst at the same time automation and artificial intelligence push for a reduction in many types of jobs.

As a member of the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) International Labour Committee I can say that the results currently emerging, and soon to be collected in a new report, show that we are facing a change in epoch. In the past, great technological innovations did indeed start by affecting job opportunities, but then later they somehow created new employment in emerging sectors. This time, things could be different. In a negative way.”

In what way will this new phase of the world’s economy be different?

“In three ways. First, the speed with which such technological innovation and automation is occurring is very fast. It affects jobs that historically, in the collective imagination, seemed immune to innovation. Suffice to think of journalists. Nowadays, artificial intelligence software is able to write press releases or cover sports events by using data matrices: producing texts that are indistinguishable from those written by humans.

The second aspect is that this wave of innovation is hitting a strongly globalised world. So, there is no guarantee that new employment will be created where old jobs are destroyed. That can occur elsewhere, in more competitive places and this can entail huge geographical movements in the short term – even considerable ones – of overall employment.

The third aspect is linked to the fact that the automation boom pushes salaries downwards, and because it is so widespread it could have an even greater impact on wealth distribution, which is already severely skewed in favour of the wealthy.”

These three elements set the stage for a very worrying picture…

“Not so much in the long term but rather in the transitions. Hence, two key conclusions. Active labour market policies should be given centre stage once again, i.e. initiatives, measures, programmes and incentives aimed at helping integration into the labour market. This is key to pushing people from one sector to another, from an area to the next, so as to prepare them for change. The absence of active labour market policies will increasingly become the Achilles’ heel of any economic system.

The second conclusion is the need for formative training throughout the entire lifecycle of the worker, a fundamental requirement in the support of such transformations. For instance, Italy has not got a specific policy for lifelong training of adults. It is a country where companies, all things being equal, invest less in training compared to other countries. But, above all, what is missing is a real national policy.

Generally speaking, on such issues there is a conceptual contradiction: companies class employees outside of the business asset category on the basis of a principle stating that ‘since employees are not under the full control of the company, then they cannot be regarded as business assets.’ This stems from the fact that employees were seen as ‘business assets’ when they were slaves. Therefore, to consolidate the fact that people should not be considered ‘slaves,’ a historical decision was made ‘to turn them into a cost.’ This concept is totally inadequate to modernity, which on the contrary should value employees as business assets in a positive sense. In some countries, companies investing in training are already given a tax relief. However, most states invest in tax relief for machines and technological innovation, rather than training.”

Could you give us an example of the practical application of active labour market policies?

“Germany has a long history of active labour market policies. Moreover, because of the recession, it revisited its entire system in 2010. The United States themselves use significant incentives to provide training. Those not implementing active labour market policies might as well copy those countries that have already introduced them. It’s a long-term investment.”

In Europe, we talk about the circular economy as leverage for new employment. In these very pages Janez Poto�nik announced the creation of 500,000 jobs linked to the Circular Economy Package. What is your take on this?

“The circular economy has two distinct impacts. The first deals with companies that, having grasped the meaning of the circular economy, manage to cut their costs, become more efficient and therefore grow, which in turn means employing more people. This is the classic way of conceiving competitiveness and economic growth, so it is correct to assume that the circular economy will produce employment.

The second is even more relevant. I will explain by way of a joke used by the entrepreneur Oscar Farinetti – Eataly’s CEO – at a conference last year: ‘I called Donald Trump and told him: we made heaps of money polluting the world. Now we can make even more cleaning it up.’ What I mean is that since the planet’s environmental conditions are not sustainable, if the world decided to start a true ecological transition and we begin to seriously clean up our mess, to make economic production sustainable and to fuel a circular economy – obviously through suitable investments – a substantial number of jobs would be created. Not necessarily long-term ones, as occurred with the big wave of post-WWII infrastructural investments which provided jobs during their peak and then stabilised around smaller figures. To this end, it is necessary to consider large investment plans which can improve the potential of economic growth as well as quality of life and contribute to the transition towards a different economic model.”

Who is making the first move?

“Partly, the private sector is already doing it, while the public sector is still reluctant to intervene in this regard. Germany thoroughly cleaned up the Ruhr area, an almost uninhabitable region, only thirty years ago. Many other European areas are still inactive, as is the case with Taranto’s steel plant, Ilva.”

Structural investments vs. welfare expenditure. National budgets are increasingly limited. How can a combination of investment policies and social support be managed sustainably?

“In my book L’Utopia sostenibile (Sustainable Utopia) (Laterza 2018, editor’s note) I tried to envisage a new way of looking at economic, social and environmental policies. If the future holds a plethora of social and economic shocks, a path of non-sustainable development is looming ahead. To tackle this, three approaches are available. The first is dystopian, where the future is portrayed as an absolute disaster and people are entrenched in bunker cities, living from one day to the next. The second is a retrotopia, as described by Zygmunt Bauman, i.e. a future that will focus on returning to the past, a world that in reality never existed. The third is that of sustainable utopia, seriously tackling the 2030 Agenda’s themes. Taking for granted that the future will bring a whole range of shocks: some of these might be small and local, and therefore absorbable; if they are of medium intensity they will have to be absorbed and we will also need to adjust. However, if they are large and therefore bound to have a lasting impact, then change will be paramount.

If we want to pursue a sustainable utopia, we must reclassify policies according to five key words: promote, protect, prepare, prevent and transform. Basic income is necessary to protect, but if it is just an income and it does not prepare people to change or to transform then it does not go very far. Today, building a motorway without taking into consideration that in a few years’ time there will be self-driving cars – and therefore not including elements such as sensor technology or infrastructure for electric cars – does not make sense. We must invest in the future whilst considering its complexity. It is true that means may be limited, but we also know that the private sector is ready to invest because there are excellent business opportunities.

If there is no clear idea about the future, no clear message will be sent to the private sector. Norway, has announced that petrol-fuelled cars will be banned by 2025; sending a clear message to the automotive industry. In order to have a clear idea about the future, the complexity of such challenges must be at the top of the agenda. The 2030 Agenda acts as a roadmap so that we can find our way around the big challenges that the future holds.”

Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASviS), http://asvis.it

“Trasformare il nostro mondo: l’Agenda 2030 per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile,” September 2015; asvis.it/public/asvis/files/Agenda_2030_ITA_UNRIC.pdf