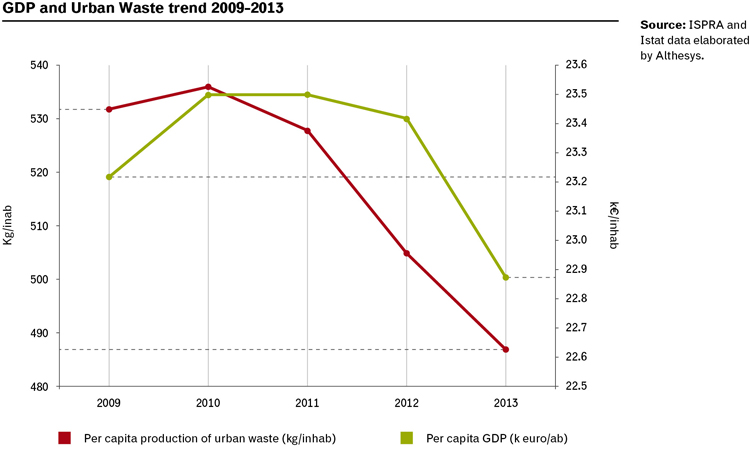

In the last few years, in Italy the situation has improved thanks to a drop in waste production and an increase in separate collection. However, the objective of decoupling waste production from GDP growth has not been reached yet, despite some positive signs between 2010 and 2011.

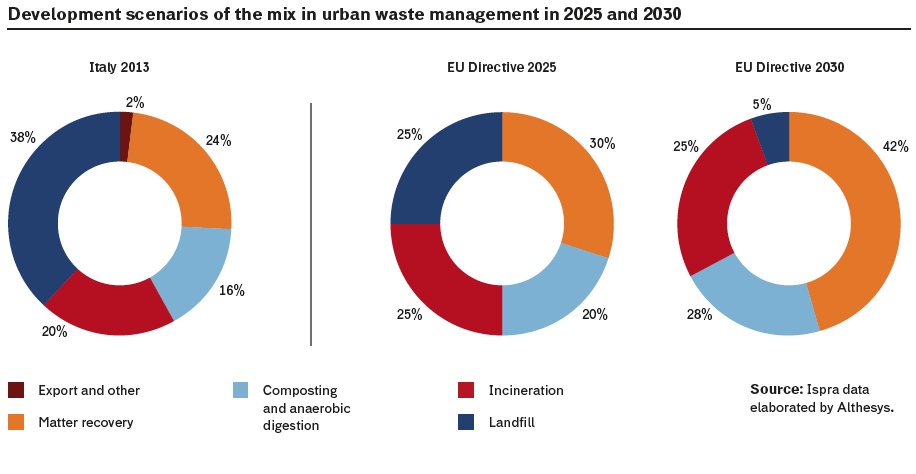

In the analyzed three-year period (2011-2013), the composition of waste management has changed, with an increase in separate collection (+4.6%), increments in quantities used for matter recovery (recycling +1.3%, composting +1.9%) and energy recovery (+1.3%), while the material sent to landfills has decreased (-5.2%).

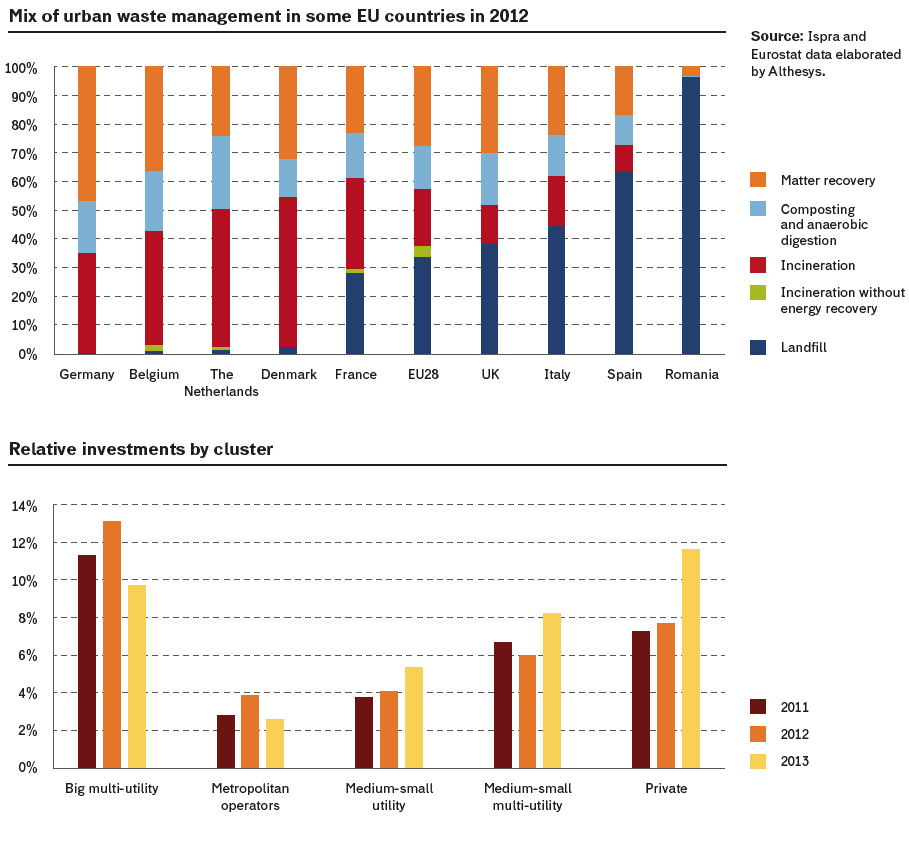

However, our country is still too dependent on landfills, which in some areas represent the final destination for over 70% of urban waste, and cannot make up the shortfall of incinerators.

The Italian situation is not too different from countries with similar populations and economies – such as France and the UK – but still lags behind North European countries that have managed to drastically reduce, if not eliminate, the use of landfills, with an increased use of incinerators, with or without energy recovery.

In these countries, incinerators do not represent an alternative to recycling, rather a complementary tool to achieve the aim of “zero landfill”, an option which is also financially viable when the heat recovered by district heating networks is used.

In Italy, the waste management and recycling industry gathers a variety of very heterogeneous operators in terms of size, pool of expertise, business field and results. The analysis of the main 70 players, collectively representing over half of the sector, shows how the best performances are those of the biggest and most integrated companies, such as the big multi-utilities that can oversee the whole supply chain.

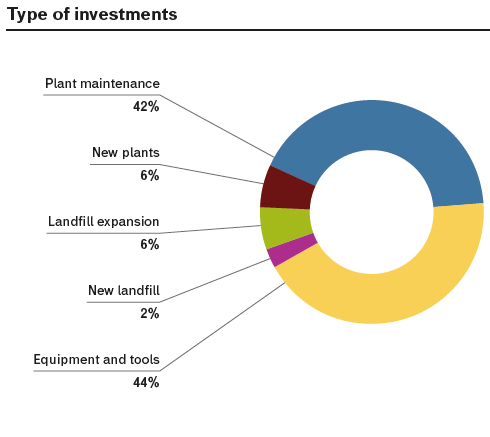

In 2013, these operators have accounted for about 50% of total investments and obtained an average relation Ebitda/Returns more than double the others (32.2%). Investments from the top 70 players almost reached a billion euros in the three-year period.

However, in the framework of a strategy of strengthening infrastructure, these investments were mainly concentrated on extraordinary maintenance and modernization of plants, respectively for 44 and 42% of the total respectively. Under the title “New Plants” we only find 6% of investments, less than in 2011-2012.

The investment trend in the waste management sector depends on a variety of factors: uncertainties over financing schemes for environmental services by local authorities, delays and inconsistencies in regional planning, lack of clarity in national legislation, and local opposition to plant construction, in particular incinerators.

In this framework, marked by difficult emergency situations, the sector has carried out important efforts in efficiency improvement and investment: many companies, despite facing a constant reduction in urban waste production, are re-organizing their plants and future investment plans, showing an increasing interest in the phases of selection and treatment aimed at recycling and recovery of waste coming from separate collection.

In this framework, marked by difficult emergency situations, the sector has carried out important efforts in efficiency improvement and investment: many companies, despite facing a constant reduction in urban waste production, are re-organizing their plants and future investment plans, showing an increasing interest in the phases of selection and treatment aimed at recycling and recovery of waste coming from separate collection.

One of the main critical points, stressed on more than one occasion by the WAS study, remains the scarcity of infrastructure. In this case as well, the strengthening of infrastructure was stopped by the same factors that caused the drop in investments. The most important factor was probably an uncompromising and often manipulated opposition to the construction of new plants.

Therefore there is still a strong dependence on landfills, which in some regions are the only solution. To make things worse, there is the progressive exhaustion of the residual capacities of landfills: at a national level, considering the same amount of waste sent to landfills last year, their residual life is estimated at less than two years.

“In order to make the situation more sustainable” the study identifies two simultaneous solutions: on the one hand, an increase in the percentages of recycling and matter recovery to reduce the flows destined to disposal; on the other, an adequate provision of incinerators to treat the residual amounts of undifferentiated waste.

The WAS study expresses its interest towards the norm contained in the “Sblocca Italia” decree, which simplifies the process for the realization of a national network of recovery and disposal plants. This regulation simplifies the procedures for the identification of sites and the construction of new plants, allowing existing structures to treat waste coming from other areas up to the saturation of their technical capacity.

All this is happening while the whole regulatory framework on urban waste is going through an evolutionary phase, both at a European and national level. In particular, most European directives regulating the sector are being revised, i.e. the framework directive on waste (2008/98/EC), the directive on packaging (1994/62/EC) and the directive on landfills (1999/31/EC).

These revisions should set new and more stringent objectives for 2030: 70% recycling, elimination of landfills, the introduction of new calculation methods and an increase in the recycling targets for packaging. To achieve such ambitious goals it will be necessary to stimulate the process of industrialization and consolidation of the whole sector, which today is still very fragmented.

The WAS study is convinced that all this is worth it: a cost-benefit analysis has been carried out on the effects of the different waste management policies (recycling, composting and incineration), each one having different impacts on the country in environmental, economic and social terms, compared to the use of landfills.

After devising two development scenarios related to the mix of urban waste management, according to the guidelines indicated by the European directives for 2025 and 2030, and estimating the amount of waste produced in the two scenarios based on population growth forecasts (source ISTAT), net benefits for the country of 3.5 to 6.6 billion euros for 2025 and 8.2 to 14.9 billion euros for 2030 have been calculated.

All this was done by only taking urban waste flows into account; it is assumed that even bigger benefits could be obtained including the waste that, despite not being calculated as part of urban waste, has a wide development potential (used tyres, batteries, exhausted oils).

Against this national backdrop, the strategic framework and potential repercussions, some policy avenues emerge from the study, together with the need for a proper long-term national strategy for waste, which values Italian industrial resources and know-how.

Firstly, the sector needs regulatory clarity and stability, but also a legislative harmonization which avoids fragmentation of know-how and overcomes the current inconsistencies and difficulties of regional planning.

New financing systems for environmental services need to be defined, as well as a revision of fiscal policies which incentivizes those “solutions at the top of the hierarchy in waste management”. Policies for infrastructures and plants are also necessary: EU objectives, be they short or long-term, demand a proper planning of investments and an optimization of the existing treatment and disposal capacities.

Better synergies in the various phases of the supply chain are also desirable, so as to promote a closer collaboration with the industrial and trade sectors and the achievement of an adequate critical mass for the realization of common investments.

The introduction of only one regulatory body for the sector could be contemplated, which would allow us to overcome the current fragmentation of know-how and responsibilities.

Info

Interview with Alessandro Marangoni

Interview with Alessandro Marangoni

Alessandro Marangoni, a business economist specialized in strategy and corporate finance, is Chief Executive Officer of Althesys, research and strategy consultancy firm.

Professor Marangoni, does the solution rest only in the hands of politics?

Yes and no; in our country we often witness an alarming disconnection between central and local levels of politics, to the detriment of the application of the norm on the ground. The solution, as you say, is therefore in the hands of the public administration, defined as a structure made up of local authorities, public apparatus but also private institutions, the social fabric and local industry.

In your study, opposition from local public opinion is one of the obstacles to infrastructure development. How necessary is correct information?

Although the attention and sensitivity of Italians around environmental issues has definitely improved compared to the past, it is necessary to raise awareness among public opinion even through journals such as this. I also find the initiatives by multi-utilities, which open the doors of their treatments plants and incinerators to citizens, very clever. I also believe it is necessary to organize visits to landfills to show the difference between them and the most advanced plants.

At the Italian Ministry for Education they are debating whether to introduce environmental education in schools. Are you in favour?

Certainly, as long as it does not take precedence over other important subjects and is presented as something attractive for young people but with a scientific foundation.

What homework should we be assigned as citizens?

All citizens can work at a “micro” level, within their household, carefully implementing recycling and teaching their children to follow it properly. Those in the field, journalists and researchers, can really help by explaining the reasons, the advantages and the enormous resources that could derive from widespread correct behaviour.