We waste a third of the food we produce, and this is also because we forget where it comes from and what its real value in environmental terms is. At Noma in Copenhagen, the second-best restaurant in the world according to “The World’s 50 Best Restaurants” ranking of 2019, fermentation is used to rediscover the value of time, as well as food, in a world that seeks short termism and immediacy. We met with David Zilber, Head of Noma Fermentation Lab and author of the book “The Noma Guide to Fermentation” together with René Redzepi, Head Chef and owner of Noma.

Fermentation is an ancient technique that is experiencing an important moment of rediscovery: what does it mean to ferment in the 21st century?

“I believe we can answer this question in two different ways: objectively and philosophically. In the first case fermentation acts simply as a mode of consumption, going far beyond its primary purpose of preservation. Seen from this perspective, it’s an effective tool to transform food into a more valuable product, whose ecological footprint becomes larger than its primary ingredients. This probably represents the vast majority of the fermentation industry, headed by the multi-billion-dollar corporations that manage the production of alcohol. On the other hand, from a philosophical point of view – an approach I’m used to taking working at Noma – fermenting becomes a means of connecting ourselves to traditional recipes and techniques; techniques that were inextricably linked to natural flows, rhythms and boundaries. By extending the shelf-life of foods, fermentation gave ancient humans the opportunity to thrive and spread. By increasing food security through preservation, the risk of suffering hunger for long periods decreased, as did the need to migrate in response to the seasons. With these thoughts in mind, fermenting in the twenty-first century becomes a way to reconnect with a past that has been largely forgotten and kept out of the public eye for about 100 years. Not that I think this has happened on purpose. Rather, it has probably happened by default. And it happens by default when people stop understanding how things are made, as companies grow so large that they become multinational conglomerates, producing everything they could ever need. Once this happens, the necessity of knowledge evaporates.”

You work with fungi, molds, fruit and vegetable peels; extracting new flavors from materials often considered waste products and “accepted” only as certain foods, as in the case of cheeses. How is the perception towards of these products changing and what role does Noma play in this transition?

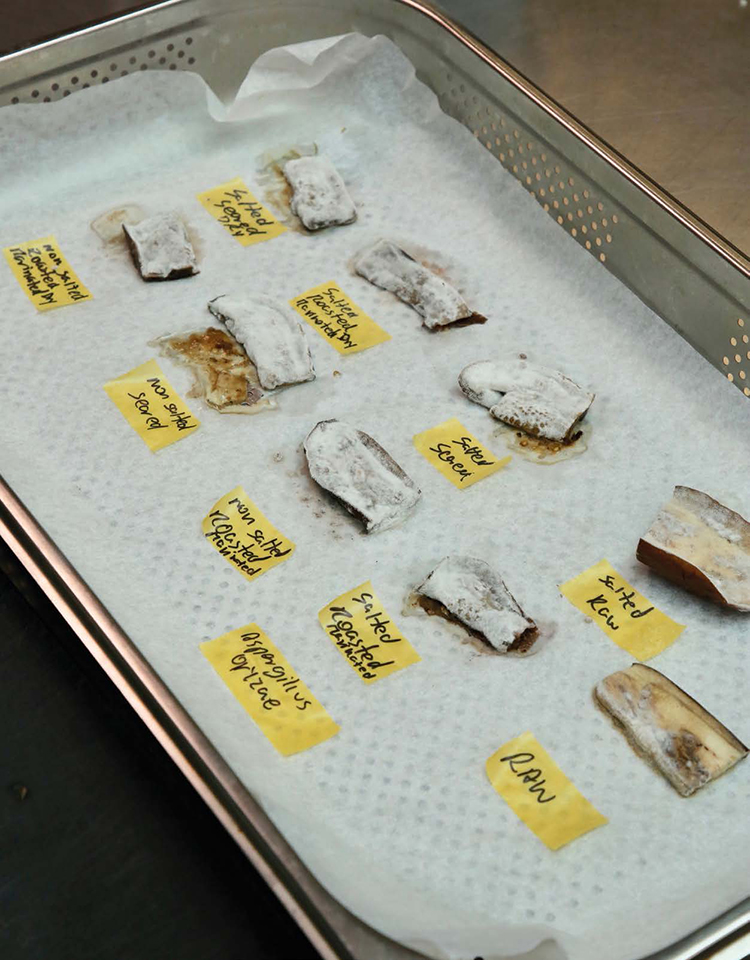

“Why is mold only ok if it covers a piece of cheese? No one looks at a piece of brie on a cheese platter and thinks it’s weird. At Noma, in preparation for the vegetarian season (Noma changes menus three times a year following the seasons, editor’s note) we experimented a lot, eventually serving three courses in a row with the same mold grown on three different bases that all ended up tasting completely different. The success of the book (The Noma Guide to Fermentation), brought Noma to the center of the zeitgeist that is fermentation. But before publishing it we were always employing the practice behind the scenes, working with it and experimenting, and we weren’t alone, for example restaurants like Mugaritz were also involved. As for the perception of disgust associated with fermentation, fungi and molds, that comes more from ignorance and miseducation. The more people understand how fermentation works and become acquainted with it, the less scary it seems. It all revolves around education and the dissemination of knowledge.”

Fermenting involves patience. When you ferment in such a high-level professional kitchen, how does your perception of time and having to wait change?

“It comes slowly, with practice and experience. It’s not something you understand immediately. At first, you’re just following directions, you wait and look at it as something stored away, with a due date for its completion that you don’t have access to. But the more you do it the more you understand it’s not about you not having access to it, it’s about a living world that operates on a fundamentally different scale from the human one. The human world is indeed very much part of the living one but we can also get so caught up in our own trappings, in our own stage performance, that we forget that there is fractally dimensional version of reality, shrunken down, where millions of organisms, invisible to the naked eye, operate on a time scale that is completely antithetical to our way of understanding the passage of time. As you collide with this fact, you grow to realize that you’re actually not the one in control. Yes, you can set up the conditions, craft an environment, care for the microbes that you employ to produce your fermented foods, but you are solely the shepherd, not the master. In a professional kitchen, turnaround times during a service can be demandingly fast. You can always increase the speed of your cooking proportionally to the urgency of getting a dish on to the pass. But this can’t be done with microbes. Fermentation requires an extreme amount of organisation, patience, planning and above all, a resignation of your control over natural rhythms. When food was preserved for our survival, time had to be invested in a technique which operated on a time scale far beyond the immediate; a characteristic feature of our current age.”

The fact that more and more chefs are talking about the environmental damage that food-related choices wreak is influencing millions of consumers, nudging them towards more sustainable and fair choices. Do you think it’s just a trend or are we starting to understand the urgency to change to survive?

“I would like to start by making a distinction: ‘helping’ does not necessarily equate to a 100% positive outcome. You can do beneficial things that may not be enough on a bigger scale or in the required time frame. Just because you have a binary between positive change and negative change (increasing or decreasing market shares) that doesn’t mean the whole world is changing one way or another. You can definitely trace a positive trend which does inspire hope but when we hear of the increase in consumer awareness about the origin of food we must not be misled and risk falling into self-referentiality. This is a small portion of the entire picture that – just because we recognise a positive trend in certain corners of the globe – is not in any way representative of the entire pie, especially if that pie is growing (of which consumption and production are). The maladaptation of our food system requires a more drastic change insofar as governance and policy making are concerned. A circular food system has to start from a deep change in the ways people farm and produce primary ingredients. The constant loss of fertile land can only mean one thing: mass migration. The transformation needed, by necessity, is radical: the conventional (industrial) agricultural model has the sole purpose of maximising productivity and profits in the short term. To facilitate the transition to regenerative and organic agriculture (which will usually cause a loss in productivity in the short term and thus demand a higher price on the marketplace) there’s a need for rapidly implemented and efficient incentives to support farmers. It’s a thorny issue that divides people’s best wishes with the frightening notion that food should cost more – all while no one’s willing to make it more expensive voluntarily. If there was more awareness about these topics, we could start building a food production system that is more secure, more diverse and almost antifragile (a concept developed by Nassim Taleb to describe that which not only is able to endure shocks but actually improves when subjected to stressors, editor’s note) to the threats looming on the horizon. We can no longer afford to turn a blind eye. Extreme events are already causing huge losses in food production. This will only lead to forced increases in prices and ever less predictable fluctuations. With this in mind, the role of the trend becomes an exponential driver of inspiration and hope: only through those impellers can we keep on imagining and building an alternative system.”

What are the major challenges we will face regarding the global food system and what will we have to fight more decisively for?

“The biggest challenge to the food system remains a properly weighted understanding, and effective communication, of the true value of food. The externalities of food production are often washed over by marketing and are never really taxed, but we have to find a way to make them explicit to everyone. This is a system controlled by multi-billion-dollar companies that trade the basic fuel of human survival purely as a stock commodity. But in reality, it’s the farmers who feed the cities of the world. The fact that the world’s population in cities outstrips those of rural areas means that we are making ourselves more vulnerable and exposed to network collapses. If we understood the value of our food system in intergenerational terms – what the present quality of soil will mean 25 years hence in the future of a child just brought into the world today – we would have a great platform for action, all because our priorities would be different. It’s an ideal vision of the world. In the real one we occupy, humans can be extremely myopic. We tend to overestimate the near future and underestimate the far, sometimes being more optimistic than is useful. A striking example of this is our enormous concern about a possible collapse of the welfare state (if and where we will go on vacations, if and when we will get our pensions), in contrast to the almost non-existent concern for mass extinction. Last weekend I was reading an article about the giant mounds that termites build, maintaining very intractably complicated underground connections. No individual termite understands that it’s building one of nature’s most complex architectural masterpieces. They all just work locally with what they have around them and only then does the organisation slowly rise out of individual actions. In many ways the global food system resembles that act of creation. Just think about all our grand, multinational human endeavors, where food and supplies are shipped across oceans multiple times before they end up on a consumer’s plate. While human animals operate on a different scale and with a different scope than termites, we can endanger our own well-being through the same mechanisms that allow those tiny insects to secure theirs. And that’s the reason why, on the personal level, we can carry on just fine while we end up creating multiple threats at the specific level (as in, species), by not understanding our own interdependence. At the end of the day, or rather, century, this won’t be about saving the world – the planet has suffered mass extinctions far worse than ours multiple times over – it’s about saving our world.”

Noma, https://noma.dk

All images: credit David Zilber