Radical, visionary, eccentric, ironic, and firmly outside the box. Shamelessly, boldly and irreverently utopian. You can love it or hate it, but you can surely not remain indifferent to Alan Marshall’s fantasy urban planning project. Alan Marshall is a New Zealander that teaches Social Sciences at Mahidol University in Bangkok, where he started a research programme for students focusing on the environmental and social future of cities. Their combined efforts led to the publishing of a beautifully illustrated volume: “Ecotopia 2121” that depicts 100 futuristic scenarios of real cities, converting them into green utopias: sometimes idyllic, sometimes disturbing and often defiantly absurd. A piece of interdisciplinary work in the broadest sense of the word, merging art, literary fiction, ecology, sociology, urban planning and design. Because, imagining the future is hard work and it’s better to draw on as many tools as possible. Above all, imagination. We had a chance to discuss the project with Alan Marshall.

How did you get the idea?

“The Ecotopia 2121 project came to life on January 1st 2013. The day before, I had flown from South East Asia to the Czech Republic to begin a semester of research. I had planned to have a first rousing evening drinking schnapps in a noisy, snowy market party; watching a giant fireworks display, bursting over a scenic medieval castle standing over a hill near the town. Alas… it was too cold, around minus 10, for my tropically-adjusted body to endure, so instead I sat inside looking out the window watching the fireworks over the city from afar and trying to decide on a new research project. The vista before me set my mind in motion and by New Year’s Day, the idea of presenting scenarios for idealistic green cities emerged in my mind.”

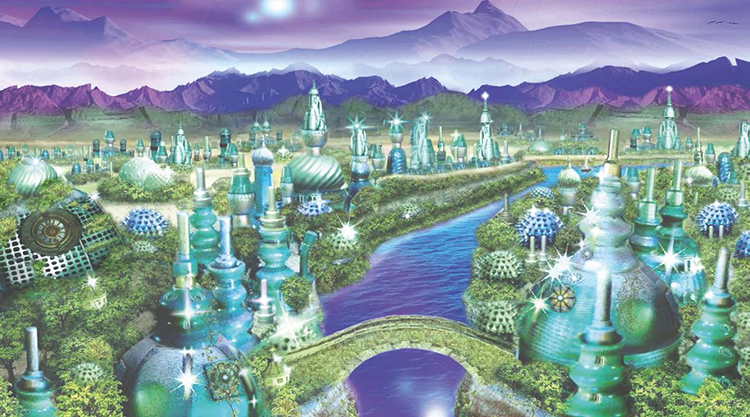

|

|

Almaty 2121 by A. Marshall

|

Where does the word “Ecotopia” come from?

“The word seems to have been introduced by journalist Ernest Callenbach when he wrote a novel in the 1970s portraying the fictional emergence of a ‘hippy-like’ Green Utopia in the Pacific states of the USA. As he used it, ‘eco’ refers to ‘ecology,’ and ‘topos’ to ‘place.’

I wasn’t directly influenced (beyond the name ‘Ecotopia’) by Callenbach’s work. Callenbach was far more earnest and direct in his imaginings of an ideal city – he was a ‘true-believer’ in the orthodox idea of Utopianism. I was more influenced by the 500-year-old book ‘Utopia’ by Thomas More, who played and jested and satirised 16th Century England as he came up with a baffling and challenging fantasy of an alternative ideal country.”

Why did you choose the year 2121?

“Around the world, in the 2000s and 2010s, planners seem to have adopted 2020 Vision statements for specific cities because they think it plays well with the 20:20 vision metaphor and with 2020AD; a future date that they seem to identify with and believe that they can influence. I wanted to come up with something that would contrast this, and therefore chose a number far off into the future that warps this clarity. For 2121, our social and design vision is not perfect and our influence may be rather tenuous. Now, because 2121 is somewhat fuzzy and uncertain for us, this gives rise to the need for constructing a vision with the help of imagination.”

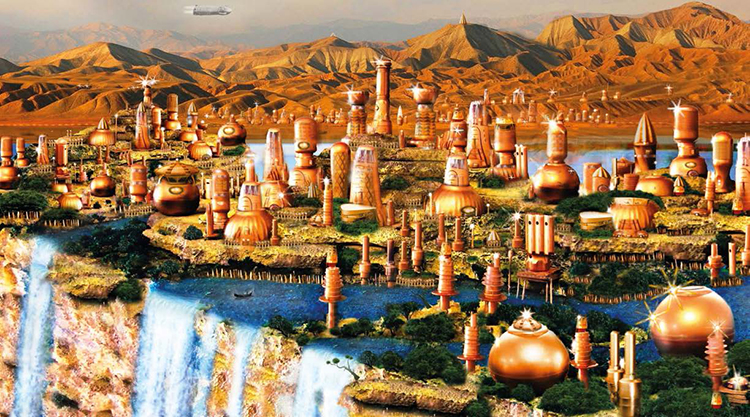

|

|

Antalya 2121 by A. Marshall

|

About the 100 cities – aside from your hometown Wellington, in New Zealand – how did you choose the other 99 cities of Ecotopia 2121? Some of them are relatively unknown…

“Some cities came to the attention of me and my students because they had intriguing or unusual tales about environmental decay or ecological hope (like Almaty in Kazakhstan, La Paz in Bolivia or Mo’ynoq, formerly a port on the Aral Sea). Others, were chosen because they are regarded as ‘Alpha’ cities that the whole world has familiarity with and therefore most audiences reading about the project would expect us to create scenarios for them; cities like New York, London and Tokyo. Other cities, like Nador, Dawai City and Gongshan emerged from the work of the university students involved in the project; who had either visited these cities or just wanted to learn more about them.”

You live in Bangkok and teach at the Mahidol University where the project was born. Why is Bangkok not in the list?

“My students and I did come up with a range of scenarios for Bangkok. However, they were all making a statement about the drastic interference of the Army in Thailand’s civil and political life over the past century. This is a topic that could be addressed if there was a civilian government in power, but at the moment Thailand has an un-elected military regime and they constantly warn ‘intellectuals’ and ‘student activists’ not to publish stuff criticising the Military. Therefore, to make sure my students stayed out of trouble, I decided to keep our ‘Bangkok scenarios’ to ourselves, at least until democracy returns to Thailand once again.”

|

|

Wellington 2121 by Alan Marshall

|

Which was the most challenging city to imagine in the future? And your favourite one?

“Bangkok was the hardest, for the reasons above. One I feel quite attached to is Birmingham because I am very familiar with the city. I lived there as a student, and because the scenario uses history, ecology, design and sociology, as well as a hefty bit of poetry, to realistically imagine a city I’d be quite happy to live in. My favourite ones though are the irreverent and satirical scenarios - like Minsk 2121 and Palo Alto 2121.”

How did you work with your students to build each vision for the 100 future cities of Ecotopia?

“As I am employed as a social studies expert at my university, the starting point was usually the formation of a ‘social change’ narrative; thus emphasising the role of either slow or fast change in eco-friendly cities. However, my students would happily go crazy with some urban plan experiment or architectural model that happens to strike their fancy. There was a precise method of scenario-building that I taught, but I have a strong suspicion that many students would draw sketches first, then think of the ‘social change agents’ afterwards, then throw in some interesting technology or unusual environmental challenge. In the end this was OK, especially if they came up with a novel contribution on how to imagine or reflect upon the future of their chosen city. In actual fact, many students initially came up with very pedestrian, or technologically-determined, or unoriginal scenarios. Therefore, I had to be constantly vigilant and try to oil-up and stimulate their social and eco-imaginations.”

|

|

London 2121 by A.Marshall

|

What’s the Fantasy Method of Urban Design? Do urban designers need an active imagination?

“The method that I developed for the students consists in a few steps: select a significant piece of work from the fantasy genre; design an urban plan for a specific real-world city based upon that work of fantasy; identify and predict the ‘agents of change’ that will give rise to the urban plan; present the urban plan in graphic form.

I use it as a weapon of critique in urban planning against those who keep assailing us with their own corporate-sponsored and technocratic urban fantasies. The Green fantasies of Ecotopia 2121 are offered as alternatives to those ‘forward thinking change-makers’ who would happily throw tax-payer money at undemocratic, techno-dictatorial urban fantasy settings like Smart Cities. Instead we created hyperloops, nuclear fusion, autonomous cars, space elevators and sea-steading.”

So, are “Smart Cities” a declining myth? Some futurologists, like Bruce Sterling, are now criticising this way of planning cities…

“Yes. I’m intrigued to see some urban theorists lauding ‘dumb cities’ as more inclusive, less-Googolised, anti-Amazonised, pro-worker, more democratic and fairer alternatives to Smart Cities. My own critique about Smart Cities refers to their problems in the less-developed world, and are revealed in the Mumbai 2121 scenario. (In Ecotopia 2121, Mumbai is designed as a city with a double face: on the one hand the city of the slums, with no toilets nor regular access to electricity; on the other a Smart Green City adopting the most advanced technologies, a hyper-technological area from which the poor are kept out author’s note.)”

|

|

Minsk 2121 by Alan Marshall

|

What do you think about the brand new projects of “ideal green cities” built from scratch, that regularly hit the headlines? Have any of them impressed you?

“Many of them are very impressive graphically. My students and I fiddled around with digital cameras, Photoshop and architectural models made out of old plastic bottle caps, so we are hard-pressed to compete with the massive budgets of a multinational architectural firm in America or China. That said, we all knew that ideal cities built from scratch are the preserve of dictators and/or the heads of giant tech firms; some out to Greenwash over industrial wastelands, some out to make vain-glorious legacy statements, others out to make billions of bucks. You’ll spot a few ‘built from scratch’ cities in Ecotopia 2121, but usually they are there for satirical purposes.”

One of the most stunning things of Ecotopia 2121 is that each city’s portrait is built both as a work of art and as a short novel: you have created an all-round storytelling about our (hopefully) green future. This reminds me of the book by Amitav Ghosh, “The Great Derangement” and his call-to-action for novelists, artists and storytellers to create a fictional imaginary about climate change and the environmental crisis. Why do you think scientists and environmental activists are not really able to reach a wider audience?

“Over the past 50 years, many eco-minded scientists have been instrumental in engaging the public and they have ‘co-created’ the environmental movement. However, the resources of the environmental movement are still no match for the power of industrialists, the power of authoritarianism, the power of state-sponsored social conservatism, and the power of global business. These sectors can use art and fantasy as well as ‘law,’ ‘capital’ and ‘policing power’ to continue the present industrial course of the globalised world. The Ecotopia 2121 project is a series of 100 suggestions about how to turn, transform, overcome and shift our industrial society into an ecological society. Of course, this means that art and imagination have important roles, as does design, politics, law, economics, engineering, psychology and all the other parts of human life.”

I know you have started working on a new project: Frankencities, a dystopian version of Ecotopia 2121. What is it about?

“Well, one of the first responses to the ‘Utopian’ scenarios of Ecotopia 2121 from readers was: ‘Yes, this is all very nice, but who are we kidding? The world is going to be be a dirty, dark, climate-ravaged, global disaster zone by 2121!’

I sympathised with this criticism, so I took it on board and am now preparing 100 dystopian versions of future cities, which assume that the environmental movement loses and the industrialists win.”

The book “Ecotopia 2121” was published in 2016, 500 years after “Utopia” by Thomas More. What is the role of utopias today? Can we find a place for new utopias in the environmental movement?

“On my part, the Utopian impulse sparks the idea that another ‘better’ social world is possible. If we are unable to even imagine a better social world, and unable to communicate our imaginings, then the world truly has become Dystopian.”

Ecotopia 2121, www.ecotopia2121.com

Top image: Moynaq 2121 by SKDiz & A. Marshall