New elections not only introduce new faces in the assemblies but they often change policies and targets in line with the new political views of the winning alignment.

The European Parliament elections that took place in the spring 2014 moved the political axis of European institutions slightly to the centre-right, so changes in the environmental policies were to be expected too.

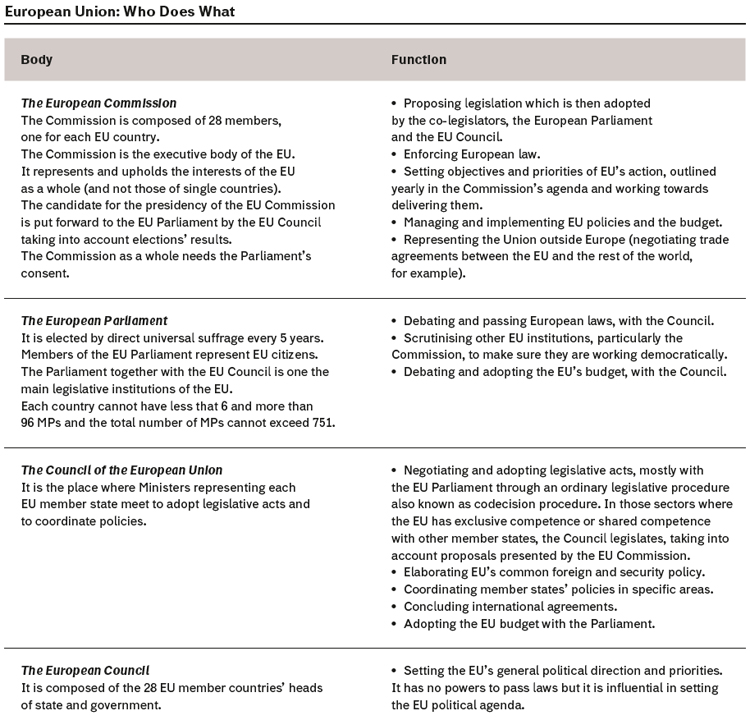

The newly elected European Parliament has obviously caused a change in the European Commission, the institution in charge of introducing bills to the Parliament that will then have to be voted on, often in conjunction with the EU Council, the other EU body negotiating and adopting the European regulations together with the European Parliament (codecision procedure).

The President of the European Commission is appointed by the European Council (the institution comprising the EU’s heads of state and government which is not to be mistaken for the EU Council), whilst the Council, in agreement with the elected President, appoints the other Commissioners. The appointment of all Commissioners, including the President, is subject to the approval of the European Parliament. So, on the 22nd October 2014, the European Parliament approved the new Juncker commission which took over on 1st November 2014.

This little reminder of what happens when European citizens elect their new representatives is useful for understanding both how much the new changed post-electoral political set-up influences the make-up of the European Commission (and its policies) and the importance of the Commission as the driving force of the European law and the new regulations that the Union decides to enforce.

Indeed, the Commission presents a bill to the Parliament and the Council, manages the European Union budget, allocates the funds and monitors the implementation of European laws.

In other words, knowing what the Commission’s agenda will be is one of the first things that European citizens and businesses want to know after the new elections.

This is why the priorities of the new European Commission were much awaited. On 16th December 2014 the Commission announced its agenda for 2015, specifying the planned actions to be taken during the year “to make a real difference for jobs, growth and investment and bring concrete benefits for citizens. This is an agenda for change.”

The new Juncker Commission emphasized political discontinuity compared to the previous Barroso Commission and stressed such discontinuity repealing 80 bills out of the 450 still awaiting a decision from the European Parliament and Council.

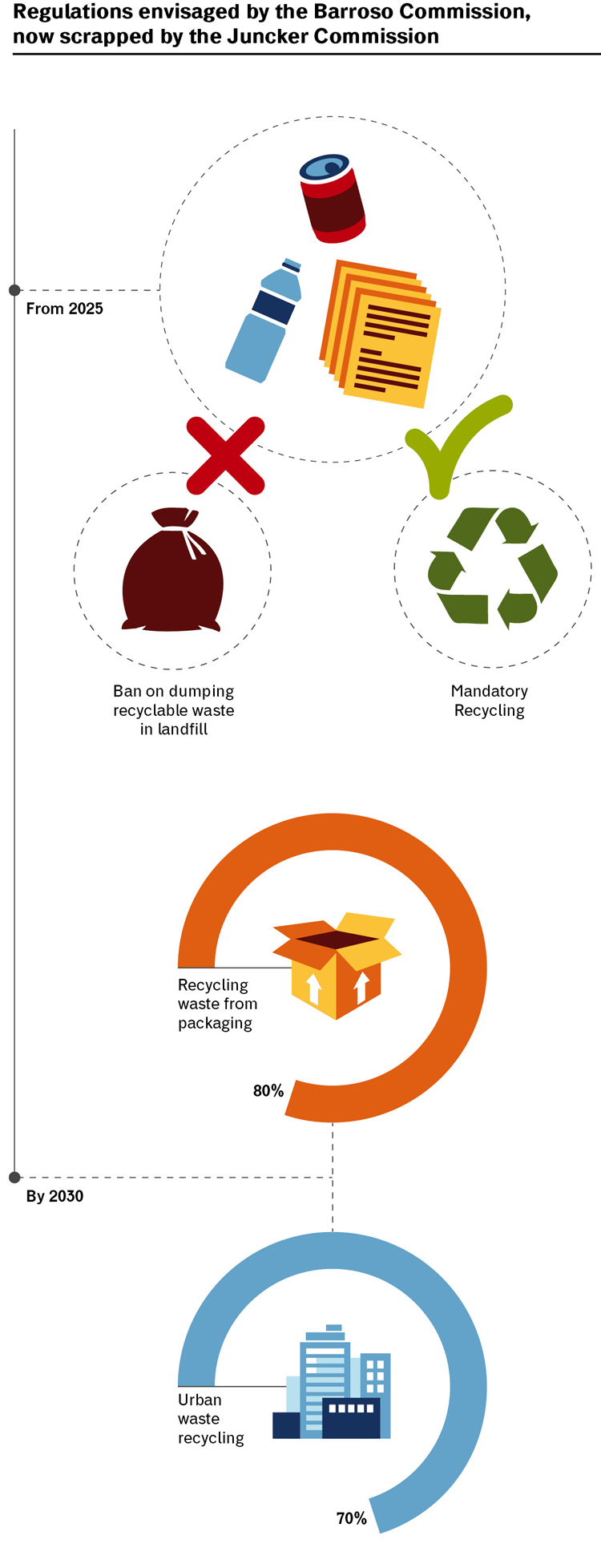

As mentioned above, one of these bills was about the circular economy that, by amending the directives on waste, packaging, landfills, end-of-life vehicles, batteries and accumulators, outlined recovery and recycling ambitious targets (perhaps exceedingly so).

According to the previous European Commission, the achievement on waste, as laid down by the directive on the circular economy, would have generated 580,000 new jobs, making Europe more competitive while reducing the demand for costly and dwindling resources.

In particular, the directive envisaged the recycling of 70% of urban waste and 80% of packaging waste by 2030 and from 2025 the ban to dispose of recyclable waste in landfills.

The economic model promoted by the directive is one where raw materials are no longer extracted, used only once and then discarded. In a circular economy, waste disappears and reusing, repairing and recycling become standard.

The proposed directive was a step in the direction of a “plan towards a European efficiency in the use of resources” (communication of the Commission of 20th September 2011, n. COM (2011) 0571) falling within the flagship initiative on the Europe 2020 Strategy for the efficient use of resources.

Why Did the New European Commission Presided by Juncker Decide to Withdraw it?

According to a Commission’s press release, bills passed by the previous Commission presided by Barroso were withdrawn for one or more of the three following reasons:

1. They were not in line with the new Commission’s priorities; or

2. They had been lying for too long on the negotiating table between the EU Parliament and the EU Council; or

3. The original proposal had been so watered down during negotiations that it could no longer serve its initial purpose.

We cannot imagine that the directive proposal on the circular economy adopted on 2nd July 2014 had been lying too long on the negotiating table or that the great political debate on it had watered it down (there was no time for the EU Parliament and the Council to discuss it).

So, we are left with the third option: the directive on the circular economy was not in line with the Commission’s priorities for 2015.

The Juncker Commission has highlighted that by the end of 2015 it will present a new directive proposal, even more ambitious than the previous one. But just the simple fact that for the whole of 2015 the EU Parliament will not discuss the circular economy speaks volumes about the new Commission’s real desire to pursue specific environmental goals.

Therefore, it seems that in 2015 the EU Commission will concentrate on promoting renewable energy, decarbonisation of the economy, reduction of energy dependence from non-EU countries while taking a pause for reflection on recycling, recovery and reuse of materials. Hopefully it will not be too long.