If 30 years ago a mid-range car would run at ten litres of petrol per 100 kilometres, today, a hybrid model only needs a little over three.

That’s an incredible evolution for the transport sector which nowadays boasts super efficient, electric and hybrid cars, built with reusable components (such as Renault’s transmissions and engines manufactured in the Choisy-le-Roi plant).

Unfortunately, in the building sector, in the residential constructions where we live or work, things have taken a completely different turn.

Even the most recent buildings mostly employ the same technologies and plants they were using 30 years ago: oil or gas boilers, mediocre insulation and no smart energy management system.

Basically we are still building in the same way as we used to in the 60s. The building supply chain is still composed of many figures (designers, architects, plant engineers, builders, floor layers) who rarely communicate with each other and much less follow an integrated plan of a building’s components. The latter are built without really taking into consideration the building’s life: as long as everything is in place when it is sold. No-one is interested in how technologies, funcions and uses will change over the years. The building thus enters in a perennial state of assistance, characterized mainly by extraordinary maintenance. So, more expensive compared to the planned one and with a higher ecological and energy footprint.

At REbuild – one of the most interesting conventions on innovation in the building and real estate sectors held every year in Riva del Garda and Milan in June and October – the product “building” and its transformation have been discussed for a long time. How should we build in the next 50 years if objectives such as a significant reduction of emissions (today the building sector is responsible for over 30% of the total emissions) will have to be achieved? And how should we do it in order to improve matter recovery, since in Europe 54% of the material from demolition is landfilled?

According to REbuild creators, “the circular building sector” is the way forward, namely considering buildings as products – maximizing their value in use – in which their life expectancy is extended since planning (rather than after a series of extraordinary works), efficiency and performance are garanteed over time. Where matter is “lent” for the contruction of buildings, always ready to be disassembled, processed and reused for other purposes or buildings; where processes are regenerative (in the management of all resources fuelling a building’s life cycle) and the quality of life and healt are optimal.

Circular architecture has a market opportunity that could generate an income of €1,010 billion by 2030, according to the estimates of ìa study Growth within a circular economy vision for a Competitive Europe developed in 2015 by McKinsey, Ellen MacArthur Foundation and Sun (Stiftungsfonds für Umweltökonomie und Nachhaltigkeit). 90 billion could be used in the Italian real estate sector, starting from redevelopment works: indeed, in Italy, there are over 13 million “sieve” buildings that need regenerating sustainably.

How should we activate circular architecture? We need to transform the “building” product. We have to use ICT for the digital management of buildings during construction and throughout its useful life, through technologies currently known as BIM (Building Information Modeling). Not only that: building regeneration must enter an industrialization phase, where costs are minimized, as well as the use of materials and timing is faster. There is a need for a social building sector, where the use of spaces is optimized (co-housing, sharing practices, tailor-made real estate products).

If in the previous article Dominique Gauzin Müller introduced the potential represented by eco-local supply chains of materials, in the next pages this theme will be developped throught David Cheshire – Aecom’s sustainability director – testimony, who will talk about the meaning of circular architecture, while Thomas Miorin will deal with market potential and the difficulties in industrializing the sector. This first “round of opinions” on the circularity of the building sector will be concluded by one of the most accurate interpeters of contemporary architecture, Mario Cucinella, introducing a human vision of the circular architecture’s spaces.

McKinsey, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Sun, Growth within a circular economy vision for a Competitive Europe, 2015; www.mckinsey.de/files/growth_within_report_circular_economy_in_europe.pdf

Interview with David Cheshire, Sustainability Director at Aecom

Interview with David Cheshire, Sustainability Director at Aecom

Edited by E. B.

Building, Dismantling and Rebuilding

When talking about the circular economy in the building sector in Great Britain, we refer to David Cheshire, the man that more than anybody else – in this field – has analyzed projects, ideas, components and solutions. Cheshire has recently published Building Revolutions: Applying the Circular Economy to the Built Environment and presented it at REbuild 2016, since circular was one of this year’s themes of the conference on redevelopment and real estate management.

The book Building Revolutions besides analysing a very high number of cases, formulates a general theory on the circular building sector. How did you come up with the idea of this book?

“In the past, I read various texts on the circular economy and this concept impressed me a lot. In order to understand how it had been applied to the building sector, I started to seek in the world those elements that were somehow resonating with the elementary particles of the circular economy. So, I collected them in my book.”

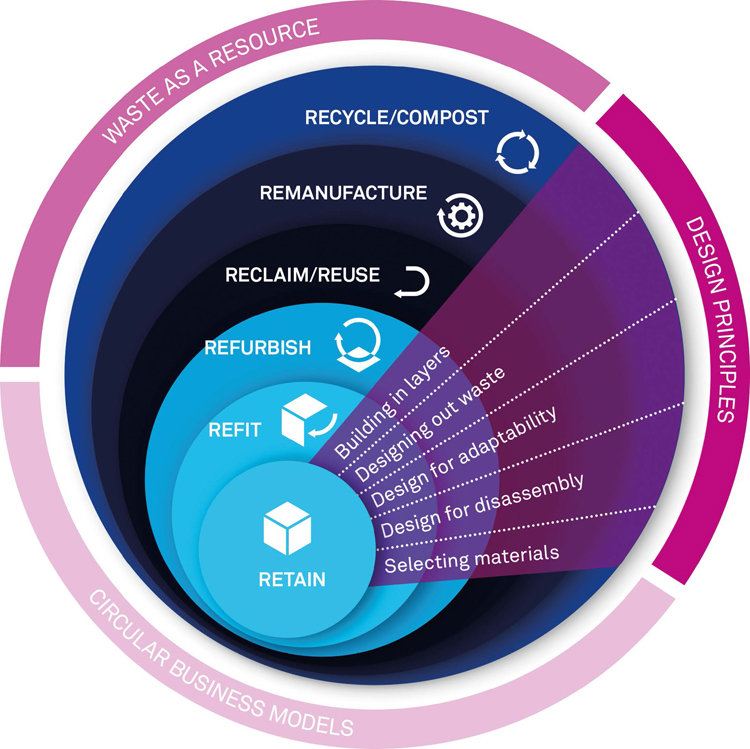

What are the strategies to achieve the circular economy in the building sector?

“Fist, we need to think about a building’s next life, i.e. what it can become after its demise. If we don’t think long term we will carry on applying a linear economy. For this reason, in the book I talk about both redeveloping buildings but also how to ‘dismantle’ them at the end of their useful life in order to use their components, thus avoiding transforming everything in waste (downcycling). In order to achieve this, planning is key, both in new buildings and redevelopments, buildings that can be dissassembled and riassembled in a variety of ways. But to do this, everything must be conceived in a fresh way, starting from the supply of materials.”

|

|

David Cheshire, Building Revolutions, RIBA Publishing, 2016

|

In the world, are there projects reflecting the characteristics of circularity?

“I came across a few buildings with a few elements of circularity, but today it is difficult to spot a project including all the elementary particles making up the circular economy. One of the most exhaustive is Park 20/20, a business park located near Schiphol in Amsterdam. It is a project that took into consideration the building’s whole life cycle, thinking how it will be able to evolve every time – disassembled and reassembled – a new type of building. It is a product in which every material used has been accurately checked, choosing those easier to reuse, recycle or compost.”

The industrial sector is starting to provide us with components manufactured according to the circular economy’s principles: I am thinking of the super efficient lights or modular carpets. Can you imagine a real growth for these products?

“Regrettably not, at the moment. First of all, it must be said that only few elements of the building can be produced with such principle. For instance, using leasing for systems is complex, since it is not possible to lease out a ventilation or heating system. The circular model can instead work on the parts of the building that are used – and replaced – more frequently: it is possible to lease out printers and computers in an office, furniture, carpets, home automation technologies. In such cases I think the product-as-a-service model can work, so that such equipment can go back to the producers, regenerated and resold.”

Today there is a lot of talk about BIM (Building information modeling), a very good software for the management of buildings to enhance their performance. What role can they play in the circular building sector?

“There is great potential. If for all buildings we had an inventory of every element, every material, with an indication of their quality and durability, end-of-life regeneration or maintenance would be a lot simpler, which would extend the very building’s life.”

What role can the EU play in promoting the circular building sector?

“Without a doubt, a first step has been taken with the Circular Economy Package. Europe must look at a circular economy on a continental scale. We cannot consider the issue separately. The more policies are activated, the easier it will work. But we can make a start without waiting for politics: there are instant benefits in adopting the circular building sector through the market. In this way, buildings with a higher value are created. So, why wait?”

Interview with Thomas Miorin, co-inventor of REbuild

Interview with Thomas Miorin, co-inventor of REbuild

Edited by E. B.

Social, digital, circular

Thomas Miorin has a mission: transforming the whole building and real estate sector. He has been promoting a reflection on these themes for years: sustainable requalification, regeneration and circular economy for our huge, current and future, real estate assets. “The market needs reconfiguring in full, thanks to digitalization of buildings and construction processes and through circular architecture” explains Miorin, talking to Renewable Matter in their office in Rovereto, participating in Progetto Manifattura, a large incubator of companies and green start-ups. In order to renovate the sector, Miorin, together with Gianluca Salvatori – Progetto Manifattura’s inventor – organized REbuild, a convention on building and real estate innovation. An alternative to the already exhausted formats of niche real estate and building, every year since 2013, REbuild welcomes the leading figures of entrepreneurs and players in the sectors in the setting of Riva del Garda. Suffice it to see the pay-off to understand that here there is a feeling of innovation and internationalism in the air: two billions of square metres to redevelop, a house every minute, real innovation. These are just a few of the slogans launched throughout the years at REbuild. For the 2016 edition, we looked even further, recommending a triad of new pillars for the building sectors: social-digital-circular.

Miorin, can the circular economy be applied to the building sector?

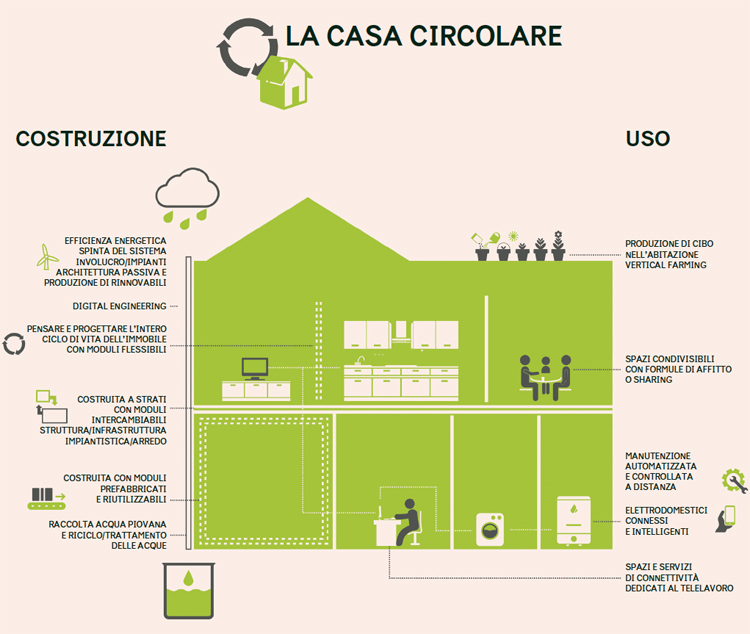

“Most certainly: re-launching the building sector depends on its reconfiguration according to a circular perspective. Such revival, though, must take place within a whole transformation of the supply chain, with I define an industry. There are already some pioneering aspects: sustainability and integrated planning for the construction and use of a building. Building takes place in layers, with interchangeable modules, with advanced energy efficiency and using reusable prefabricated elements. The building use includes food production, space sharing, connectivity and teleworking, remote-controlled automated maintenance. Within circular architecture, the idea of waste disappears, whether it be energy or people’s time. Everything has a value and – through a convergence amongst new available technologies and a new organizational process – it is possible to achieve a building sector able to regenerate public as well as private assets, to give new energy to Italian economy, to reduce dramatically pollution in cities and redifine national energy balance.”

Talking about circularity, though, is still premature: in Italy there are no examples.

“This because all the various phases of the building’s life as a product are not covered, in that the real estate supply chain is still highly fragmented. First of all, the planning phase is still detached from the use one. Then, there is another rift in the life of a building, namely its financial management: usually, real estate funds have a seven-year deadline, which is far too short. It is the current dissociation of such cycles that creates the impossibility not only to think of the whole life cycle of buildings, but also to carry out home improvements and energy efficiency operations.”

So, how can we act to reunite the cycles?

“The actual shift to a circular economy entails starting to see a real estate product as a product-service. Going from the current building sector to the circular one involves two stages: an industrial-technical phase and an economic-financial one, linked to the definition of parametres agreed within the supply chain. This entails for example, measurement systems, supply chain organization, third-party companies measuring and guaranteeing performance and value, new financial tools such as green lease, due diligence, new business models (building as a product).

“But the most important part of the conversion is the technical aspect. Today, we are not faced with a regenerative process. At best, we are talking about an aesthetic/functional redevelopment with minimum impacts of energy efficiency.

“I reckon that the circular economy in the real estate sector means an industrialization of the building sector: the only technical-economic organization able to supervize a product’s life cycle in the capitalistic economy is indeed the industrial sector. It is no coincidence that the most advanced sectors in the application of the circular economy are the industrial ones, as many case studies reported by the MacArthur Foundation. Because industrial players are the only ones able to transform a product in a service, they are the ones with the technical-financial resources to control many different sectors, with structures and resources to govern a vast temporary sector that includes even the end of life or the passage to the next.”

In Italy, what’s the current situation like in this sector?

“Today, in Europe, 98% of the building sector is made of small and medium enterprises; 90% are micro-enterprises with fewer than ten employees, living for 72% in a building sector of planned and extraordinary maintenance. Then there are a few European large leaders in the field, able to supervize the whole building’s cycle, which do not come to Italy because they have not got market interests.

“Besides, this sectors made of artisans has a huge productivity gap of hours/employees.

“In the manufactuting sector, there is an estimated hour/employee productiviy or around 88%, in the building sector such percentage drops to 43%. Basically, 57% of the time in the building sector is waste, it does not produce value in the end product. Then, there is the issue of matter recovery: in Europe, in demolitions, 54% of materials is landfilled. But we can do a lot better: in some nations, such percentage drops to 6%. At Progetto Manifattura, in Rovereto, we managed to recycle 98% of a decommissioned industrial area of about 5 hectares. We have already buildings conceived as ‘material banks’ and others completely dismantled and rebuilt with new functions and uses, without losing any materials.”

Where must the new building and real estate business be headed?

“In this phase I should thing towards prefabrication, digital survey, building digitalization, digital manufacturing, producing on an industrial scale what is then customized by artisans. This already eliminates most waste while minimizing the building site. Not only that: in this way, the management phase is also optimized because products are transformed in products-services, which is super efficient from an energy point of view and where the value of energy saving is internalized rather than passing the buck. Moreover, spaces must be planned to be modular and their use must be optimized. There are buildings that after four/five years of life as offices become nursery schools: they are planned in layers, with the planning principles of the circular economy.”

In this way the function of a product as service is maximized.

“Today, it is possible to rent a room for a few nights, parts of buildings are used as locations for events, schools that in the evening become places for social gatherings. This can also be a revolution for the public sector as well. The government does not need a school, as a building. It needs a healthy and clean room with 20 °C, from 8 to 13, with two functions, chairs and blackboard. From there many other functions can crop up. The value of the building grows according to its use while the land value falls. Actually REbuild gave prominence to the circular economy because the building sector, if up until now has remained practically unchanged, it must now redefine its product-service and enter the industrialization era. So, we must decide whether to guide or not a process that otherwise could be organized by third parties. It will obviously entail an extensive redefinition of the work load, roles and competences. The building sector, more than any other, will bring along changes: there will be more engineers working on digital models covering the energy-planning of simulation and organization of an artisan’s systems. From an employment point of view, an increase in productivity will entail a fall in the number of employees. But the circular economy will also bring other jobs, with new unimagined professions.”

REbuild Italia, www.rebuilditalia.it

Progetto Manifattura, www.progettomanifattura.it/en

|

|

Photo by Luca Maria Castelli

|

Interview with Mario Cucinella, architect

Edited by E. B.

Buildings: Everything but the Oink

Mario Cucinella is an icon of Italian sustainable architecture, of both social and environmental sustainability. Simplicity, sharing, environment studies, flexible and healthy spaces. Style arises naturally, the project is dictated neither by design nor by functionalism. People inhabiting buildings always come before those designing them. We asked him to talk about the relationship between architects and the circular building sector.

In Italy, the building sector debate currently seems to focus on sustainable requalification.

“In Italy there is always the same problem: there is a great debate, many meeting and conferences on requalification and regeneration but in reality the mechanism has not started yet.”

We start talking about the circular economy and building. Is there a new thought spreading amongst architects?

“For years, the industry has been working on the issue of material, secondary-raw material recycling and life extension of the product. In architecture things are more complicated: it is easier to create a recycled tile than starting a planning, building, demolition and reuse process in construction. This is a much more complex process requiring a knowhow still unavailable on the market. But, it is clear that even the building market is moving towards this issue, for example in the reuse of materials: in buildings everything is used ‘but the oink.’ They are dismantled, even for economic reasons, recycled and reintroduced into the production cycle. But for this to happen, we need a sector ready for action. Because if circularity of matter if possible, if building and planning processes have already moved forward, behind we need a sector able to deal with dismantled products and capable of reintroducing them into the market and managing them in new ways.”

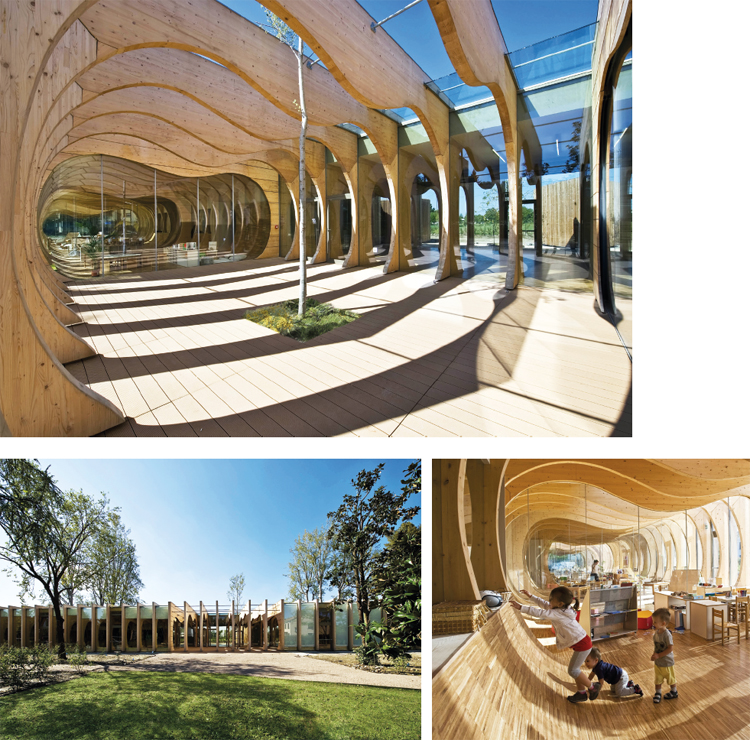

Could you give us some examples of your projects that try to integrate the circular approach to building?

“In Guastalla we built a nursery school which is 100% disassemblable and recyclable because it is basically made of two materials: glass and wood. The wood used comes from a circular production chain linked to forest conservation; even for glass there is flourishing recycling sector. Besides, in this building we installed a rainwater collection system. This water is used for flushing toilets thus avoiding having to use drinking water. Thus architecture has also an educational function: the nursery explains to its children that the water used to flush toilets is recycled rainwater. From a structural point of view, the building has being mechanically located on the site thus making disassembling easy, so much so that it could disappear without a trace. But we must also think about the life expectancy of a building: had we only thought like this in the past, with building that could be disassembled and reassembled, today we wouldn’t have any old town centres. When it comes to buildings, reusing is easier than recycling. For instance, the building where I have my studio, in the 1970s it was a warehouse, tomorrow it could become a loft, the day after tomorrow who knows. So use and life are as important as the possibility of the reuse of materials.”

The circular economy issue is crucial. As for objects used only a few times and then thrown away, buildings are often used only for a few hours a day, for instance schools, community halls, auditoria and offices. How should we rethink the architecture of these places in order to maximize their use?

“The paradox is carrying thinking of building new spaces when we already have them. Maximising the use of buildings makes sense but we must find managing solutions. The public administration must see this as an economic opportunity: if a school space is used for eighteen hours instead of the normal six/eight hours, we rediscover a value that we already had but that we could not see. So, instead of constructing new buildings for meetings or community gathering centres, we can increase the use of an underused public building. This is already happening in the private sector: Airbnb for example, a website that makes private rooms available to travellers. This is an important phenomenon demonstrating that the circular economy moves around significant cash flows.”

Have you ever designed a building with multiple functions in mind? A building that embraces this philosophy and includes this multi-use predisposition in its very design?

“In Pacentro, in the Aquila hinterland, we designed a school embodying this very principle with vertical classrooms (used by nursery children and primary and secondary school pupils, editor’s note) since it has very few students. Classrooms are located around a central area. It is a flexible space available to community: it is a library, but it can also be used as a small theatre, as a socializing space, used by the cooking school or as a hall for parties and birthdays. So from the very planning, buildings are designed to meet a real need for multivalence.”

|

|

Pacentro School (Aquila). Circularity stems from shared participation All images ©Mario Cucinella Architects

|

Top-down design or participatory process? How do you tackle a circular project?

“Architecture must capture people and communities’ desire. I think capturing this desire is the most interesting aspect of our job. Pacentro’s school is a good example. It is not a big building, but it gives you an idea of what can be done: use, recycle, time sharing in a building created by listening to citizens.”

Does the future hold fluid buildings, blank slates to fill with new functions?

“For example Sala Borsa in Bologna is a library, a piazza, a place for internet or to read newspapers, to study, a place where you can get a book from and spend tow hours reading your things or writing. Multitasking buildings, to use a more contemporary term, are an attraction for many people, because everyone in that space finds a solution to his/her problem. And this is the function of a building.”

|

|

Rendering of the project “A sustainable school in Ghaza.” In 2014, another nursery shool of his, also in Gaza, was destroyed during an the “Protection Margin” Israeli operation

|

Your house in Bologna is a total open-plan area. Can walls limit use even in private homes?

“Today we use industrial spaces more and more. One wonders ‘Why?’ Besides the reutilization of a building, an open-plan area can be interpreted in many different ways and can chance according to people’s desire and life styles. The building sector is still trapped in the 1950s: it builds rooms and technologies. We need flexible architecture with planning looking to the future. Maybe building spaces that do not already have a defined function but which is defined by the way they are used. An architect must not impose functions. Architecture must become an essentially poststructuralist operation.”

|

|

Details of the School Project in Pacentro. A multifuntional central space and modular classes to maximize the use of public space

|