When they created the Product Life Institute in Geneva in 1982, Orio Giarini and Walter Stahel stood as lonesome cowboys exploring the newfound land of the circular economy. Indeed, during the 60’s and the 70’s, affluent Western economies had swept pre-industrial product reuse and material recycling practice into oblivion. Ever since, business models, product innovation, private consumption and the economy at large aimed for infinite growth and universal wealth.

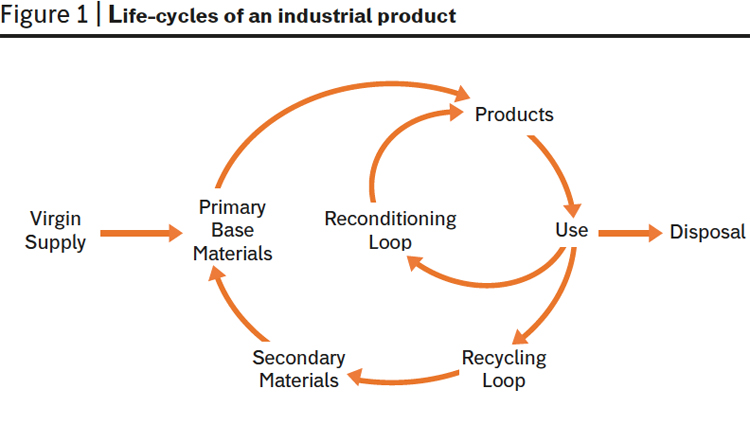

Giant caterpillar excavators stand as the symbol of ever-moving boundaries of the linear economy incessantly claiming: new land for agriculture, more mineral resources for industries, additional roads to accelerate growth, extra landfills to host ever-increasing wastes... No need to be an expert to figure out that someday, some time, the economic bonanza may come to a halt. That is why the lonesome cowboys gathered their rope into a lasso and moved on to catch a more viable solution: the loop economy (see figure 1).

To walk the talk, the Product Life Institute immediately spearheaded new business models and tested them. Among these, a venture initiated in the early 90’s with Winterthur, recycled spare parts from the insurer’s damaged cars park while creating new employment opportunities. Later that model spontaneously replicated and adapted across many countries. Another, now familiar, case concerned laundry machines: it showed the advantages of “selling goods as services” in the shape of intensive shared utilisation. While most washing machines are designed to last about 15 years and deliver 3,000 washing cycles, semi-commercial washing machines now commonly used in launderettes are designed to deliver 30,000 cycles over the same period of time and consume water in a loop. Customers pay a fixed amount per washing cycle that includes operating costs (water, energy, space), as well as maintenance and repair costs.

More importantly, Stahel advocated that, by retaining the ownership of the goods they produced, companies would be able to increase their earnings. They would do so by selling services rather than goods. Thus, they would establish a continuous “relationship” with consumers, one that would ensure incomes on the longer term. By adopting such a business model, he argued, companies would eventually go out of their way to retain and maximise the embedded value of their products. However, until recently, only industrial product designers and academia stood as the supporters of the so-called cradle-to-cradle approach. It would take several more years, and the advent of the knowledge-based economy coupled with the outburst of the circular economy, for such an envisaged shift to become operational.

So much so, the first Circular Advantage Business forum, dedicated to applied business models pursuing the circular economy, took place in London on June 7-9, 2015.

Major companies such as Alzo Nobel, Dell, Philips, Veolia, Hp, Carlsberg, Interface, Marks & Spencer and several more, convened to discuss and share experience on how to implement new circular models. Accenture Strategy consultants provided backbone analysis and outlined emerging models based on research released in 2014. Companies show-cased how they tapping new revenue streams, reducing costs and risks, strengthening their relationship to consumers and reaching for the fuzzy concept of “sustainable growth” with much determination. So it comes as no surprise that specialists in emerging trends, such as the Paris based Futuribles, spotted and pinned down the ongoing far-reaching change.

The Accenture research mentioned above involved interviewing over 50 executives and reviewing 150 case studies of the circular economy, and established that, today, you may look at the Circular Economy (CE) in terms of five fairly distinct business models.

1. The first among the novel business models embraces the circular supply chain; it comprises companies that provide renewable, recyclable, or biodegradable inputs as substitutes for linear ones. Such enterprises have identified a business opportunity in finding new materials that can replace single life-cycle inputs. Akso Nobel’s development of bio-based chemicals stands as an example of such an approach, as in the case of bio-based coatings for food-packaging.

Alzo Nobel set itself very ambitious sustainability targets. It measures progress made at achieving these targets along the entire chain and not only through its own operations, i.e. from oil and gas extraction to the disposal of products. In practical terms, this means that the company involves its suppliers, customers and their own suppliers and customers. Bio-based coating for food packaging is an example. In 2014, Akso Nobel introduced a new technology that allows paper cups for cold drinks to be fully recyclable. Although the company supplies a very small component of the final product (the paper cup), the new coating has made a difference for its clients.

2. The second business model is based on resource recovery; strictly speaking, it has been around for decades. It is based on material recycling and industrial symbiosis, and is triggered by companies that recover value from outputs generated either from their own operations or from different parts of the value chain. It creates new sources of value for those companies receiving the materials. In other words, it is about looking at waste as a resource, about returning bio-products from the manufacturing process, or about the classic recycling or upcycling of materials. For instance, one GM plant recycles about 90% of its manufacturing waste and, by doing so, has developed a landfill-free manufacturing process. Today it generates over a billion annual revenues by reselling the by-products of the manufacturing process.

Similarly, another Akso Nobel project looks at waste as a resource. Because much of the company’s waste is either landfilled or incinerated, the decision was taken to look at ways to convert discarded materials into useful raw materials. Hence, waste gasifier technology and technology to extract base chemicals from the resulting gas is under development. Resulting products are to become the raw materials that will feed into chemicals and coatings operations.

Developing such an innovative solution implies much collaboration among different companies along the chain in terms of expertise, knowledge and capital. While one company develops the gasification technology, another supplies and handles the waste, typically a waste management company, a third company produces the chemicals by extracting them from the gas. Overall, it is quite a complex business model to develop, but a necessary one to ensure that Akso Nobel is first on this slot of the CE.

3. The third model proves how Mr. Walter Stahel’s intuition and understanding of the new frontiers of the CE were correct: it is about product-life extension, i.e. extending the working life-cycle of products and components by repairing, upgrading and reselling products. It means shifting the emphasis of businesses from volume sales targets towards performance and the durability of products. Google’s Project Ara provides a good example. Ara is developing a modular mobile phone that allows any consumer to replace parts and aspects of the mobile phone to extend both its life and its durability.

4. The fourth CE business model emanates from the sharing economy based on sharing platforms. A direct result of the IT revolution, that reaps a series of previously unimaginable economies of scale, it draws on the idea of using digital platforms for renting, sharing, swapping, lending, gifting, bartering products and services. Effectively it allows increasing the velocity and the utility of an extremely vast array of assets. Indeed, today, most assets are under-utilised: nearly 80% of things stored in a typical home are used less than once a month and, as most of us will have noticed, 97% of the time cars sit parked and are unused while they occupy the common ground. This is how we can get more velocity and utility from resources. The impact of AirB&B in increasing the utility of people’s homes provides a good example of how such a model is pervasive. Meanwhile new models of sharing platforms continue to blossom.

5. The shift from products to services, where consumers can lease products or pay-per-use, underpins the fifth and last model termed as the functional economy. Again, the lonesome cowboys we met at the beginning of our journey through these novel CE business models, proved they were following the right path towards the future. The functional economy opens a market for all those companies or individuals who want or need greater flexibility in usage, rather than ownership, of the asset. What was often strictly contained within the boundaries of neighbourhood relations and economics is now accessible and tradable. In addition, this is yet another way to get much greater utility from the resources employed. At a business level, Philips’ lighting service and Michelin, which is offering tyres as a service, based on a very innovative model where a consumer can pay per miles driven, are following this path.

At this point, it is worthwhile taking a closer look at the breakthrough model developed by Philips to deliver lighting to its customers. Marcel Jacobs, the company’s Director of supplier sustainability, participated in the webinar leading to the London Forum Innovation.

On this occasion, he described in some detail how his company is moving towards a circular model. For Philips, the path from linear to circular does not represent an extension of the usual way of doing business. Indeed, because of the great variety of products the company puts on the market, the ongoing shift implies the development of brand new areas of competence. These new areas must be able to meet global trends both in terms of challenges and, more importantly, in terms of opportunities.

Diminishing availability of resources, associated price increases, and the expansion of the planetary middle class stand as the major challenges. So the next obvious question becomes: how can Philips benefit from meeting these challenges? To answer these interconnected questions, a number of other relevant trends were included. Among these the advent of “big data”, i.e. the ability to know more about the company’s clients to identify the most significant patterns of consumer behaviour. For instance, it allows having a better picture of lighting needs in buildings and other infrastructure. Furthermore, Philips itself may become a provider of “big data” with positive fallout effects on other businesses.

Another intriguing trend lies in ongoing changing consumption patterns and how to deal with them. The implications are numerous and far-reaching. For example, the shift from owning a product to accessing a product affects both product development and product maintenance. Besides, it implies moving from the concept of transaction to that of relationship. All of this has led to considerable testing of possible innovations and about ways to do business differently. As a consequence, and as will be described later, a very strong need to foster collaboration and partnerships has arisen. Moreover, this is only a starting point.

Moving from the notion of “product” to that of “product as service” represents a fundamental change in the direction of reducing resource use. Accordingly, Philips has identified four essential enablers to make it happen.

1. Change the business model. As already pointed out, moving from a product sales model to “use as a service” model has far reaching implications. The main shift is in thinking in terms of five, ten, maybe even fifteen years long contracts. This is very new ground for a manufacturing company. For instance, it is important to understand what happens in terms of warranties. Also, monitoring what kind of impact your novel service-product has over time, and verifying the service you provide meets the requirements of the customer, needs that appropriate key performance indicators (KPIs) be developed. In turn, the new KPIs need to be built-in the new business model.

2. Reinforce design. Yes, the second key enabler is about design. If you start selling a product as a service, you have to be able to verify whether you are selling the right product. Since Philips owns the product over its entire lifespan, it needs to know if it has enough details about its performance and its usage over time, if it knows how to maintain it properly, if it can later come up with a different technology or solution. Again, all of these issues need to be solved in the product design phase.

3. Foster partnerships and collaboration. A practical example will best describe such enabler. Take the case of parking lighting or office lights. Generally, Philips products are sold to an installer who mounts the product in a building, then the owner of the building has some sort of facility management contract with a company, which in turn has some kind of contract with a maintenance company to take care of the product and its performance. By offering a lighting service, Philips enters that market and suddenly becomes a much more important player. One that may affect the other companies. Hence the need to develop a mutually beneficial partnerships through collaboration. The issue becomes: who are the right partners? Thus, it becomes essential to develop criteria to establish who the right partner is, what a right partner is, and how to maintain the relationship in the long run. At least this sounds familiar! So it comes as no surprise that, to achieve this, it is imperative to be open and transparent with its partners. This includes the customer who needs to fully appreciate the short and long term benefits of having the best quality of light on his premises.

4. Develop reverse logistics. The fourth enabler lies in talking upfront a very new business issue, namely that of reverse logistics. A product lasting 10 to 15 years poses a completely new set of questions: what happens at the end of life of the product? Can it be taken back for upgrading? Can the product be reinstalled later? Eventually, may it be installed in a different location? What can be done with its components, and how does this tie in to the innovation cycle? To what extent can critical components be recovered, and can these be used within a new product, or will they sent back into the material recycling loop? These are some of the issues Philips is dealing with. To make things even more challenging, not every customer can be satisfied with the same solution. There is no standard fits all. Philips is pretty much learning by doing, this whilst looking and tackling the numerous challenges that continue to appear on the path towards the circular economy.

Over thirty years down the road since the creation of the Product Life Institute, the novel business models Giarini and Stahel had put on the drawing boards are now being refined, implemented and diffused by all forward-looking companies. Coupled with the digital revolution and based on partnerships, these models are paving the way for the advent of a mixture of sharing economy and green economy, one that takes responsibility for its impacts, whether they are social or environmental. Such are the business models adopted by the companies that have no intention to be swept away by the legacies of the linear economy.