We could define glass as a noble material. Made with naturally-derived raw materials, has been used for as many as 5,000 years and today it can be separated and recycled – with economic and environmental advantages – potentially ad infinitum.

Glass does not change its physical and chemical characteristics in its recycling and processing of new products phases: this makes 100% recycling possible, without any loss of mass and of its intrinsic properties and with no need of more virgin raw materials.

Basically, products made through glass cullet will have the same characteristics as the recycled ones and at the end of their life will be sent to the glass producing factories, thus achieving a virtuous circle that could potentially last forever.

What Is Glass Made of?

Glass is made with a blend of minerals widely available in nature. The most commonly used material is silica (sand) which melts at high temperatures and when it cools down it solidifies. To lower the melting temperature, during the processing network modifiers or melters are used. So, in order to obtain containers or food contact materials a blend of raw materials (mineral) containing vitrifiers or melters, i.e. silica, sodium and calcium through a blend of sand (SiO2), soda (sodium carbonate Na2CO3) and marble (calcium carbonate CaCO3) is used.

Glass has a structure similar to that of a liquid, so much so that it is defined as a highly viscous fluid, at its rigid state at room temperature.

The viscosity curve, from the fluid to solid state, varies directly on the temperature.

In order to know more on glass, you can visit the Friends of Glass portal, a European community, promoted by FEVE, supporting information campaigns on glass properties.

Friends of Glass, www.friendsofglass.com/gb/?setlan=gb

Thanks to its properties, glass can fit in perfectly with the definition of circular economy. In this respect, the European Parliament Committee on Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE) has recognized something important with regard to the circular economy.

From a study of materials and recycling supply chains, in Europe some research is being carried out on those materials that, besides allowing a production and recycling supply chain within the circular economy, for their intrinsic physical and chemical characteristics can be defined as permanent materials. And glass is a candidate for this status.

The Committee itself recognizes a higher value to these materials. The legal opinion of 20th October 2016 about the changes to the 94/62/CE draft directive on packaging waste reads: “Wherever possible, member States should promote the use of permanent materials with a higher value for the circular economy, in that they can be classified as materials that can be recycled without losing their intrinsic value, regardless of how many times the relevant material is recycled.”

Within the debate of the so called “Circular economy package,” the Committee has voted in favour of the proposal to introduce incentives for the use of all permanent materials.

Such stance has thus triggered a debate on future European measures regarding recycling, incentives for permanent materials and their legal recognition.

According to their promoters, such legal measures should encourage such an efficient use of resources, by favouring really circular business models thanks to the possibility to use more than once resources obtained through separate waste collection.

Is Glass a Permanent Material?

The study “Permanent Materials in the framework of the Circular Economy concept: review of existing literature and definition and classification of glass as a Permanent Material” led by the Experimental Station for Glass and commissioned by FEVE (European Container Glass Federation) is answering this question.

Glass represents one of the best examples of permanent materials now being used both for its intrinsic physical and chemical properties, and in relation to its current recycling supply chain (from separate source collection, to treatment and reuse of the secondary raw material in glass packaging-producing factories), and the widespread knowledge amongst European consumers of its recyclability.

The document of the Experimental Station for Glass has identified the essential criteria for its definition – in the absence of a legal one – of a permanent material and analysed the presence of such requisites in the production of the glass recycling supply chain. In doing so, the Experimental Station has taken into consideration the following studies: British standard BS 8905:2011 “Framework for the assessment of the sustainable use of materials – Guidance,” the first document to ever propose a definition of Permanent Materials; Carbotech Final Report 2014 “Permanent materials, scientific background.”

Below you will find the characteristics that must be present and according to which glass falls within the definition of permanent material.

It must be degradable during its life cycle and its recycling must be possible ad infinitum. Glass does not undergo significant degradation during its life cycle, nor during its recycling phases. From glass cullet the same original products can be obtained and in the same quantities, in terms of weight. Glass chemical composition, its viscosity curve in inverse proportion to the high temperature, allow melting possible glass cullet to create new products without any loss in mass nor in its intrinsic characteristics and glass quality. Just to give you an example: from a kilo of glass cullet a new object of the same weight can be made. So, ten glass bottles can become fifteen jars and then go back to ten bottles of the same quality as the original ones, without adding any new primary materials.

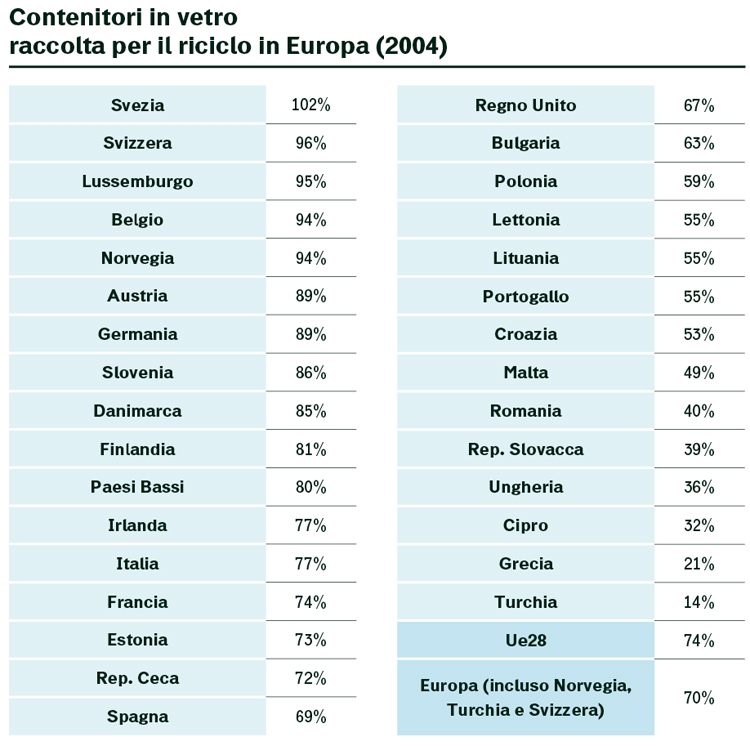

Recyclability must be technically possible. In order to talk about a permanent material, recyclability must not be only theoretical, but also technically feasible. And this applies to glass for which in Europe information campaigns have been organized and a separate waste collection well distributed supply chain (albeit with different results, but with high rates anyhow) and a recycling industry has been established, whose technology allows the removal of impurities (ferrous, organic, glass-ceramic etc.) and 100% recycling of landfilled glass. Indeed, it must be said that in some EU countries such as Denmark, Sweden or Belgium, glass container recycling exceeds 95%, meeting the target of a closed circuit on a national scale (FEVE data).

The material must be useful (and not a hindrance) to sustainable development. Recycling glass cullet produces great benefits for the environment, in view of sustainable development and the green economy. The recycling supply chain reduces exploitation of non-renewable mineral resources, it involves energy saving – because glass recycling requires less energy compared to energy produced with raw materials – a reduction of CO2 and less landfilling.

Thanks to the use of cullet to produce new glass products, in 2014, in the EU over 12 million tonnes of raw materials have been saved, CO2 emissions have been reduced by over 7 million tonnes, equivalent to removing 4 million cars from our roads.

In terms of energy to power furnaces, there is a 2.5% saving every 10% or recycled glass.

The process must be compliant with the law. The use of material, its recycling process and possible disposal must be compliant with current regulations.

All the advantages for the industry

Thoughts by Vitaliano Torno, FEVE’s President and Adeline Farrelly, FEVE’s Secretary General

We asked Vitaliano Torno what the advantages for the environment and for the glass industry of the recognition of permanent materials by the European Union might be.

“By using recycled glass in a closed circuit, the industry reduces dramatically the use of other virgin materials. Legislative measures should encourage a genuinely efficient use of resources, concentrating on truly circular business models, in other words, the same productive resources time and time again. Permanent materials, which can be recycled ad infinitum without losing their intrinsic properties, should be supported and promoted. Their recognition will contribute to the reduction of Europe’s dependence on the mining industry, soil and fossil fuel consumption for packaging production, but also for the manufacturing of other products and tools. Moreover, industries committed to using such materials in their production systems should be supported. This – Torno concluded – would be a very important step forward for a truly circular economy in Europe.”

The proposed incentive mechanisms for permanent materials include their adoption within the EPR (extended producer responsibility) schemes. Adeline Farrelly, FEVE’s Secretary General will explain the advantages such recognition would entail.

“One of the basic conditions to allow recyclable materials to be permanently recycled in the form of new products is to have a perfectly functioning EPR scheme. EU legislation on waste – currently being re-examined with the Circular Economy Package – should help the EPR schemes act as support and incentives for separate waste collection of permanent materials, through investments aimed at infrastructure and at information systems addressing citizens about the correct ways to collect.”

Farrelly adds: “As an industry, we are already heavily investing in order to reuse recycled glass within the production cycle. This is indeed the main raw material for us, with important environmental as well as economic benefits. As an industry we would like to use more of it, provided it is of a high quality and in a competitive market. We believe that the recognition of a higher status to permanent materials in EPR systems, will be the incentive necessary for the market to increase the use of permanent materials, such as glass.”

“Permanent Materials in the framework of the Circular Economy concept: review of existing literature and definitions, and classification of glass as a Permanent Material,” June 2016; feve.org/glass-is-permanent-material/

Info